‘Spellbound’ at the Ashmolean review – ‘bewitching’

With something for historians and die-hard Harry Potter fans, Spellbound, the Ashmolean’s latest exhibition is certainly bewitching. Spanning four rooms and eight centuries, the exhibition reveals a continuum in human thought: 180 objects from the 12th century to modern-day Europe. But what is most striking is how the collection – brought to life through 3D installations – exposes something that remains at the core of humanity. Spellbound suggests that, as remote and archaic as the term ‘magic’ may sound, to this day we have deep-rooted urges to control our fate through supernatural means.

In this world, magic is not some intangible mystery, but a set of environmental conditions rooted in the physical. The astronomical collection by Nicholas of Lynn (1424) shows detailed guides to sanguine operations according to the position of the moon. The curators describe these phenomena as “beliefs and actions of people engaged in a delicate balancing act between environmental pressures and use of medical and magical interventions to control their destinies.”

Salvator Rosa (c) National Gallery, London.

Spellbound’s layout encourages immersion into this set of environmental supernatural conditions, by placing modern, light and sound installations at the end of the display of objects and manuscripts. One highlight, Katharine Dawson’s “concealed shield” exhibit, allows the visitor to stand amidst the sounds and lights that would have once, and perhaps still are, been experienced as supernatural.

Elements of the exhibition hint at a positive side to supernatural beliefs. ‘Magical thinking in prison’, a tapestry courtesy of fine cell work, is a moving example of modern man feeling victimised by environmental pressures, and attempting to take control over his destiny. A glistening wall of locks from Leeds City Council reminds the visitor of our continuing desire to seek higher powers in matters of desire and commitment, with romantic inscriptions such as “a me vie de coer entier” (and some less romantic phallic depictions…). Love, perhaps, is the best example of a continued hope that powers may be invoked to induce infatuation and commitment: an array of potions, spells and love charms indicate this is the case.

Leeds love lock. Photo: Ceri Houlbrook.

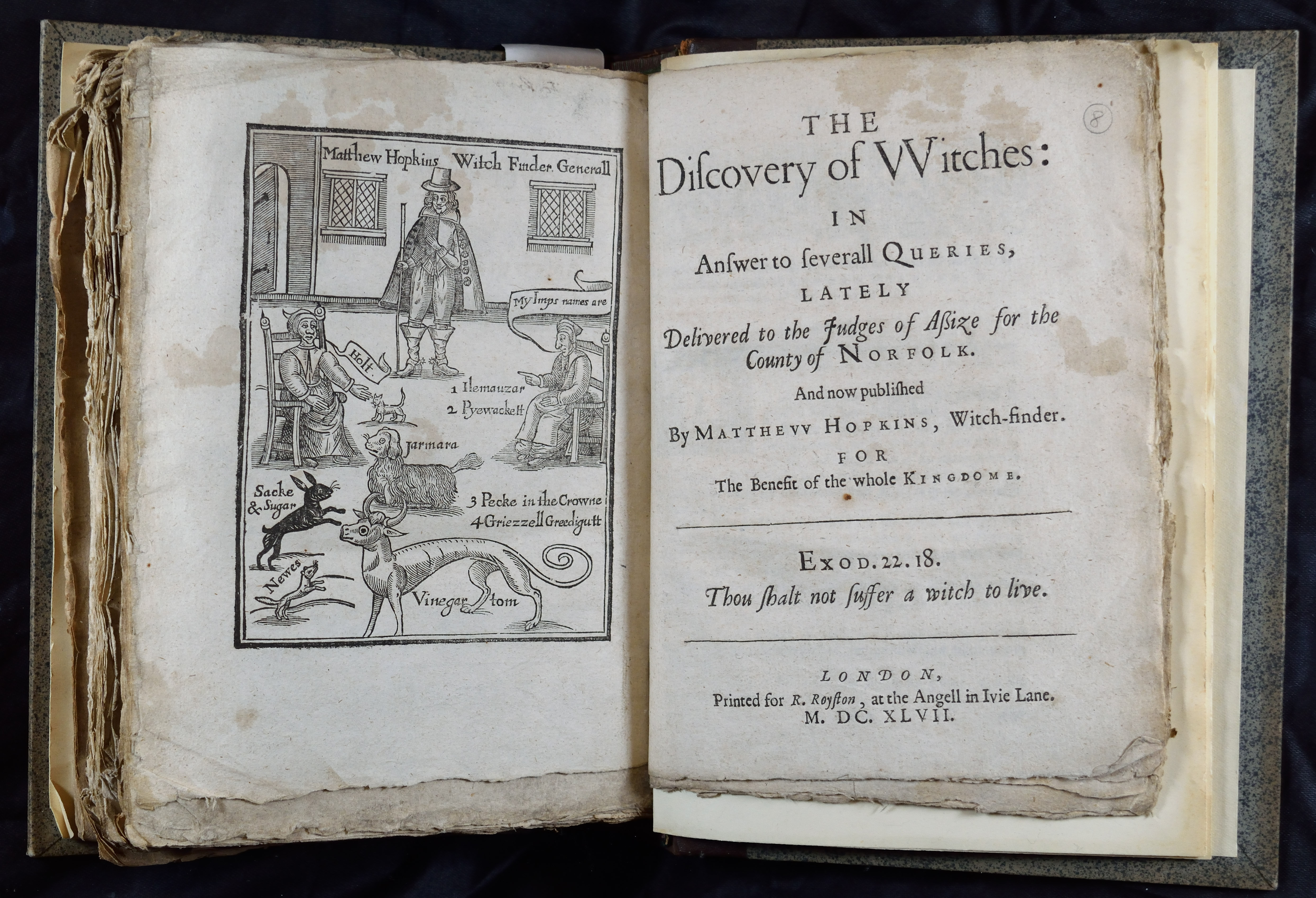

Discoverie of Witches (c) Queen’s College, University of Oxford.

But the curators are careful to steer away from glamorising superstition. A whole room is dedicated to witchcraft, and the terrors caused by the persecution of witches. Albrecht Durer’s sketch of a gnarly naked woman riding backwards on a goat particularly captures the transgression of witches supposedly opposing “every positive value in community and society”. This is one of a vast collection of mesmerising sketches on display, from which a disturbing sense of prejudice and doom emerges. Indeed, a number of manuscripts depicting gruesome images of witch trials lead up to a booth, named “love and loss”, where emotionally charged audios of witchcraft accusations are played. An authentic witch scale looms over the visitor and medieval texts describing torture for “witches”. Annie Cattrell’s ‘Veracity’, illustrates the dark mystery surrounding such accusations through the medium of film: flickering flames and candles light up a dark room.

Poppet (c) Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, Boscastle.

The Ashmolean rarely strays from art and, not that the exhibition is completely removed from the theme, it is nevertheless an unsolicited success (perhaps this is tied to Xa Sturgis’, director of the Ashmolean, second life as a successful magician). One disappointing aspect, aside from the limited nature of the displays, is the lack of diverse representation. There are no more than a handful of artefacts gathered from outside Europe. Yet the firmly Anglo-centric focus, especially with regards to the witchcraft section, causes other artefacts to appear almost in isolation. Be warned: if you are looking to consider magic and its influence in different countries, you will be severely restricted here.

It is easy to see how the likes of JK Rowling could be inspired by mandrake roots and magic mirrors into inspiring a generation – for us commoners, though, it is more likely Spellbound will inspire some particularly vivid nightmares. The pursuit of eccentricities, nevertheless, remains yet another less than rational commonality in human nature, and will no doubt make visitors come to a clearer understanding of themselves.

Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft is at the Ashmolean Museum to 6 January.