Home is a state of mind

by Kathleen Farmilo | March 9, 2017

Home, to me, is in a constant state of flux. Regardless of physical location, being a multinational citizen brings with it its own unique homelessness. For those brought up between nations, or families, defining ‘home’ is even trickier. We’ve come to think that living in one place your whole life is not only unattainable, but also slightly boring. It makes sense, then, that as our world becomes wider, so should the concept of ‘home’.

For me, home has never been easy to define: I have lived in nearly as many houses as I have lived years on earth. The things we normally associate with home (a house, a street, a county, a country) become less important. There is a collection of seemingly random elements that make me feel like I’m at home: opening the front door to a wall of heat on a forty-degree day, catching the first salty whiff of the ocean while driving down to the coast, re-reading Harry Potter in bed. These are less to do with specific places or even the people I enjoyed these experiences with, despite them being intricately and indelibly connected. It is the feeling of contentment and safety, doped up with a heavy hit of nostalgia.

Of course, there is a certain danger in the lure of nostalgia. It’s like returning to your childhood town during university holidays to find that nothing has changed, while you have. The places glorified in our memories feel like an old favourite song, now slightly bittersweet. It’s easy to feel like Frodo at the end of The Return of the King; the Shire is just a bit too familiar after a plethora of fundamentally life-changing experiences (much like moving to university). However, when we reduce the idea of ‘home’ to feelings and experiences, they become more readily transferable. It becomes easier to feel at home wherever there is ocean, a cup of tea, a friend. The idea that home is not a constant is hopeful more than anything else. As we look at the world around us, we see millions of uprooted people, forced out of the only towns and villages they have ever known by war and poverty. For many, ‘home’ is nothing more than a vague sense of displacement.

In the absence of physical homes, our cultural identity is what can connect us to each other, and perhaps even our environment. Being Australian means, to most, having a suntan, a can-do attitude and a healthy supply of ‘mateship’. In the U.K., the suntan is slightly harder to come by. While on the surface they might not seem wildly different, it is inevitable that each people has its own peculiar character. In England, there is this inescapable feeling of trying to find one’s place among thousands of years of tradition. There’s a hierarchy intrinsic to its history; institutions older than bloodlines. The characters of these nations are expected to reflect on their subjects. This can lead to the slightly lonely feeling of being not quite Australian enough for Australia, and not quite English enough for England. It’s something most migrants and immigrants feel, struggling to navigate our way through pre-existing notions of what a nation looks like.

If England feels traditional, there is surely nowhere more traditional than Oxford. All new students feel the same expectation, and I’m sure the same desire to prove that they belong. It’s this same strive that permeates the very essence of being international. For me, proving my belonging is twofold. There’s a sense of innate loneliness that comes with the reality of being the only person of a certain nationality or background. There are parts of my identity that no one can relate to, or empathise with; and a distinct sense of separateness from my friends and family in Australia. I have no sense of ‘going home’ at the end of term. To the people closest to me, I am an alien, the symbol of an institution and a life that they, too, struggle to relate to. There is a sense that I should feel like I belong. I was not expecting to have culture shock moving to England, a country that I have constantly visited since childhood. And yet, the fact that I experienced this shock is in itself jarring. It raises the question of whether feeling like you totally belong to a place is natural, or easy. Sometimes, I feel a strange desire to shrink, to reduce myself to something thoughtless and transparent: almost to revert to childhood. There’s a sense of safety in this anonymity, much like the safety of being in the backseat of a car, the radio humming softly, knowing that you are safe in the hands of your driver and your destination. Perhaps it is the destination which is belonging. I don’t know whether I belong to Oxford. I do know that I belong to the people I love here, just as much as I belong to the people I love scattered across the globe. Feeling at home can be the result of nothing more than kindness.

A close friend of mine, Viv, is Italian-American. We were discussing how feeling ‘at home’ intrinsically ties itself to a sense of belonging, and she told me, “I am my own home.” Being multinational is a unique experience. While there are feelings that belong to all of us, a sense of belonging is innately personal. Language is intimately tied to this. Viv phrased this as feeling that she was “the American living in Italy, and during the school year [she] was the Italian living in America.” There is the idea of trying “really hard to belong everywhere at the same time, to overcompensate.” Speaking a different language at home and at school, with your friends, or in the street, is not something I can relate to. For my multilingual friends, the idea that one nationality is associated with anything derogatory or negative by their families can add to another sense of displacement. Viv’s expression that she is “desperate for a sense of belonging, alternatively dramatizing my allegiance to each nationality in an attempt to validate my own conflicted identity” is particularly apt. All the conflicting elements of our nations exist within us. Sometimes, it is hard to choose which of these characteristics we best want to emulate, or accentuate It is much more empowering, and much harder, to make a home out of yourself. Being at home anywhere in the world, being at home when you’re alone, is no easy middle ground. But I would argue that it’s the happiest.

If our identities are shaped by the places we live in, the things we see and the people we love, it makes sense that we all carry a little bit of home around with us. Eighteen years of never feeling quite settled in one place has led me to feel settled in my bones, in my college bedroom, in pretty much anywhere I can find a cup of tea and a good conversation. As traversing continents becomes an increasingly more common life decision, being able to feel at home anywhere is a valuable skill. But this ‘home’ can also have a downside. Home can become a set of complacent values you lug around from place to place, like the ratty old armchair your mum insists on hanging on to. It is important to know when to let go of these things that make us comfortable and simultaneously hold us back. Redecorating the walls, so to speak, is not necessarily a bad thing. And when the people you love are a phone call away, it’s a lot easier to feel content just about anywhere, easier to settle in to your first and most important home: yourself.

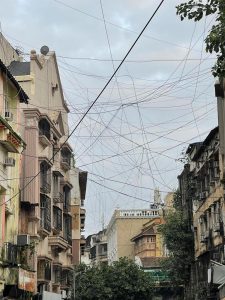

Photo credit: flickr