The Museum of Broken Relationships

by Polly Mason | May 8, 2016

What do a noseless garden dwarf, a pair of pink fluffy handcuffs, a cuddly caterpillar with some of its legs torn off, and a dunce cap all have in common? Each of these objects forms an individual exhibit in what is unquestionably one of Europe’s most innovative, original, and daring museums.

The Museum of Broken Relationships is one of a whole host of tourist attractions nestled in Zagreb’s beautiful, historic Upper Town. And yet this museum, made conspicuous only by the people milling around its entrance, is anything but conventional. The concept upon which it is built is beautifully simple and, crucially, universal. Anonymous individuals donate tokens of love, both material and immaterial, and an explanatory text, in an effort to move on from a former relationship. As a rule, all donations are accepted and no restrictions are imposed on either the object itself or the accompanying text, which makes for a truly curious and diverse museum.

The idea emanated from the personal experience of Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišić, who broke up in 2003. When the relationship ended, they joked about setting up a museum to house the mementos of the time they had spent together. Three years later, the seeds for such a museum had been sown. Grubišić and Vištica began to collect objects from their relationship, encouraged their friends to do the same, and realised that this way of channeling and overcoming pain was something that could benefit everyone. It was not long before the public was first able to cast their eyes upon the mementos of broken relationships. In 2006, public access was granted to the exhibition, described by its founders as “an art concept which proceeds from the assumption that objects possess integrated fields—‘holograms’ of memories and emotions—and intends, with its layout, to create a space of ‘secure memory’ or ‘protected remembrance’ in order to preserve the material and non-material heritage of broken relationships.”

Grubišić and Vištica’s ‘art concept’ began as a travelling exhibition. After first being shown to the public in Zagreb the exhibition was displayed across the world, first in surrounding countries including Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, before moving onto Germany, Singapore, Argentina, Turkey, England (Sleaford, to be precise), Taiwan, and beyond. Having been visited by more than 200,000 people, it was finally installed permanently in 2010. It still tours occasionally; the next planned trip abroad for the exhibition is to Boise, Idaho.

“They [Vištica and Grubišić] very often repeat how they never even dreamt it could become as successful as it has”, says Ivana Družetić, the museum’s Head of Collection and Touring. ‘Successful’ is somewhat of an understatement. For something that started out as a personal project, the museum has been adorned with acclaim and awards. In 2011, at the European Museum of the Year Awards, it was presented with the Kenneth Hudson Award. This prestigious accolade is granted to a museum, person, project, or group whose unusual, and perhaps controversial, achievement has challenged common perceptions of museums in modern society. The Museum of Broken Relationships’ capacity to transcend borders and inspire cross-cultural compassion and understanding was explicitly praised by the EMYA jury. They rated the importance of public quality and innovation as fundamental elements of the museum.

The Museum of Broken Relationships has taken heartbreak and turned it into something spectacular. The void created when someone leaves causes us to cling to what we can: letters, memories, and objects – regardless of the detrimental effect. Visiting the museum is a cathartic experience. Unsurprisingly, this has made the idea of donating an object highly appealing. The museum’s collection is so large that it can only exhibit around 15% of it annually. Donors assume the role of the artist and channel their emotion into creativity. They can use the museum to express themselves artistically, but also to heal emotionally. This is clear in ‘An ex-axe’, one of the museum’s most well received exhibits.

An ex-axe

1995, Berlin, Germany

“She was the first woman that I let move in with me. A few months after she moved in, I was offered to travel to the US. She could not come along… I returned after three weeks, and she said, ‘I’ve fallen in love with someone else. I have known her for just four days, but I know she can give me everything that you cannot.’ I was banal and asked about her plans regarding our life together. The next day she still had no answer, so I kicked her out. She immediately went on holiday with her new girlfriend while her furniture stayed with me. Not knowing what to do with my anger, I finally bought this axe at Karstadt to blow off steam and to give her at least a small feeling of loss- that she obviously did not have after our break-up.

In the 14 days of her holiday, every day I axed one piece of her furniture. I kept the remains there, as an expression of my inner condition. The more her room filled with chopped furniture acquiring the look of my soul, the better I felt.

Two weeks after she left, she came back for the furniture. It was neatly arranged into small heaps and fragments of wood. She took that trash and left my apartment for good. And so the axe was promoted to a therapy instrument.”

Catharsis is not something experienced by donors alone. It extends, too, to visitors. The objects on display are both personal and public. They present one aspect of one individual’s experience, the significance of which no outsider can fully comprehend. And yet seeing, and reading about, them provides comfort; we are reassured that life does go on. The donors have reached a state of acceptance. Družetić accurately pins down one aspect of how one feels upon leaving the museum: “[Visitors recognise] how alike people really are when it comes to matters of love and pain, regardless of race, nationality, religion, sex, and cultural background. There is comfort in knowing that we all go through the same rollercoaster of emotions when it comes to love, its highs and its lows.”

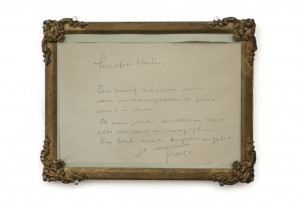

The final room demands the most emotional endurance. The visitor is reminded that romantic relationships are not the only ones that break. A particularly harrowing exhibit is a mother’s suicide note.

My mother’s suicide note 1959 – 2007

Amsterdam

“Dearest H

To write a letter under

these circumstances is almost impossible.

I wish you and M. and M.

all prosperity possible.

And lots of love and happiness.

Your Mamma”

This room also houses a ‘confessional book’ for visitors to write a message. Victoria Rasbridge, who visited the museum over the summer, says that writing a few words, whether they’re about a personal relationship, a thought on the museum, or something else, “allowed [her] to channel all of the emotional investment and introspection [felt in the museum] into something productive”.

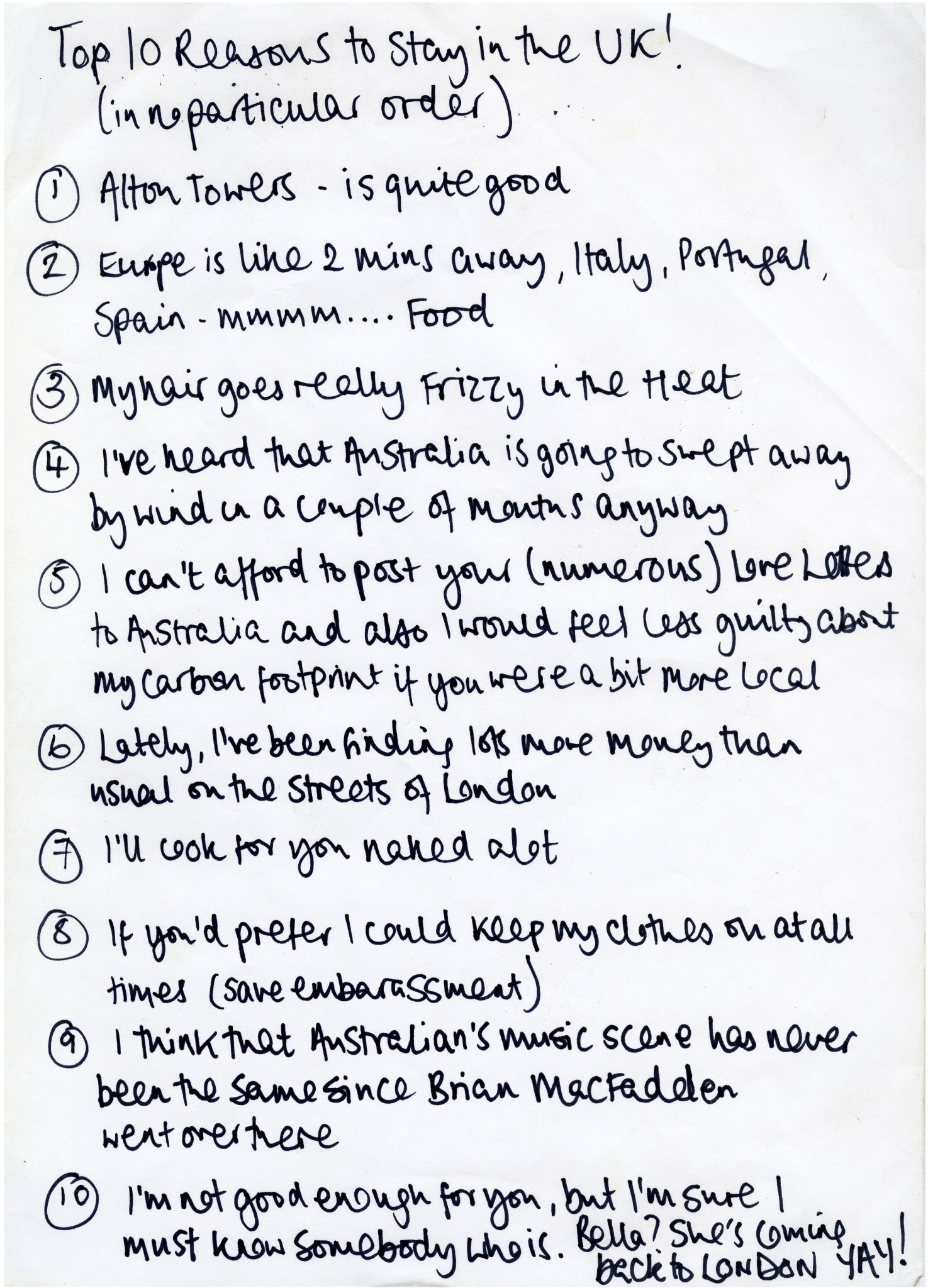

The suicide note is not the only display that upsets and unsettles the visitor. A significant number of items do not make for easy viewing. But the sadness they elicit is offset by the more lighthearted pieces. I remember finding some of the exhibits side-splittingly funny. Take “A List of 10 Reasons to Stay” (pictured), described by a visitor I spoke to as her “favourite display for comedy value”. The list itself is wittily written and its style elicits both empathy and sympathy in the reader; the accompanying description, however, speaks volumes.

A list of 10 reasons to stay

3 weeks, December 2011

London, UK

“I met her at the beginning of December, not wanting anything serious and definitely not looking for a girlfriend. After constant contact I knew that she was something special, and the thought of her returning to Australia on 29th December was not something I was looking forward to. So I wrote the list, but forgot to include number 11: These feelings don’t happen to me often.” The poignancy of this particular exhibit stems from the donor’s use of humour to convey his emotional attachment-something that undoubtedly strikes very close to home for a number of visitors.

The museum offers an exchange of experiences. Visitors gaze in on the lives and former relationships of strangers, and it’s then up to them to draw their own conclusions about the nature of human relationships. Physical reactions to the exhibition obviously differ – one visitor apparently suggested that the museum should provide the service of free hugs to those shaken up by the exhibits. But my own experience of visiting the museum, echoed by everyone I have spoken to about it, is quite different. The Museum of Broken Relationships serves as a stark reminder that nobody is immune from hardship and suffering, that everyone is fighting or has fought their own battles. This timeless message crosses all borders and goes some way to explaining the museum’s enduring popularity and ability to remain tucked away in the back of visitors’ minds.