E is for England

by Cormac Connelly-Smith | June 3, 2015

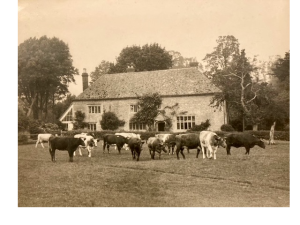

‘Englishness’ is a term that has grown as flat as our beer, and as meaningless as our national anthem.‘Englishness’ is something to be rolled out every four years for the World Cup in order to sell Mars Bars and Gillette Razors. It has been appropriated by the sort of people that think the phrase “two World Wars and one World Cup” is an essential dictum of British foreign policy; by tweedy men wiping their scandal-grubbied hands on the flag in the hope that it will wash them clean. This annexation of our national identity matches another loss: that of our natural landscape. Since the end of the Second World War, our rural areas have gradually emptied, or shrank, their inhabitants ebbing away to the cities or to post-war prefab towns. This retreat leaves our shared national identity undefended and vulnerable to those who wish to hijack it for their own ends. As our natural landscape has become polluted, so too has our national identity.

The River Falcon gurgles sightlessly beneath my local high street, condemned to a nocturnal existence due to the construction of Clapham Junction station in the last century, built to shuttle workers faster across the smoking metropolis. I identify as a ‘Londoner’, but the roots of that identity run only as deep as the paving stones. It is a dangerously empty identity, at risk of being filled with poison and bile. For many the hollow artificiality of the city is the only landscape that they know, as they are kept separated from a shrinking and increasingly privatized natural landscape. The disconnect from nature forces an identity and set of values that are drawn from the materialistic bedrocks of the urban landscape.

The land outside and in-between our cities we simply call ‘countryside’. It is forgotten now, except for visits to see relatives, or perhaps to walk the dog on something that isn’t ringed by road or rail. Many of us share the sentiment of Philip Larkin’s 1972 poem, Going, Going:

‘And when the old part retreats

As the bleak high-risers come

We can always escape in the car.’

The car now has become like an isolation ward, separating us from the ‘countryside’ that rolls by as we sit and stare passively out of the window. The motorways themselves are extensions of the city, symbolic of the post-war flattening of national identity into the pursuit of capital – Great Britain Plc. Each day we lose more and more of our natural landscape, each day we lose more and more of our soul as a nation. I am not advocating a mystical return to nature. There will be no druids, and no torch-lit ceremonies on misty moors. But there is undeniably a sense of ‘soul’ and magic that resides deep within the natural world. There is a passage in Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk that illustrates this beautifully, as she recalls her childhood explorations, realizing that “What happened over the years of my expeditions as a child was a slow transformation of my landscape over time into what naturalists call a local patch, glowing with memory and meaning.” The natural world is teeming with “memory and love and magic” in a way that the cold, artificial urban world cannot rival.

The labelling of our rural areas as the ‘countryside’ suggests that they are something to place on the ‘side’, so as not to distract us. The dissolution of our rural and natural vocabulary bodes ill not just for lovers of the English language, but for all of us. The erosion of our natural vocabulary destroys the value we give to the landscape. It is not easy to build over and pollute dales, brooks or fens; it is far simpler to build on the ‘countryside’. In Landmarks, Robert MacFarlane notes “the power that certain terms possess to enchant our relations with nature and place,” and his work attempts to recover this “word magic” before it is too late. Generalising words such as ‘trees’ or ‘hill’s are built over the linguistic ghosts of words like ‘copsy’ or ‘hagginblock’, before they themselves are replaced by concrete and tarmac. The loss of these words also represents an unravelling of the patchwork of culture, dialects and regions that make up a wider notion of ‘Britishness’ or ‘Englishness’. The ‘English’ language is not only that of the ‘bloke down the pub’, but the waterman and the fen-stomper also.

There has long been a link between the natural landscape of these Isles and the sense of national identity, a link that has been broken in the post-war era but which should be forged anew. One of the most famous and evocative patriotic passages in the English language emphasizes the physical fabric of the British Isles:

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

Shakespeare’s notion of ‘England’ was therefore, that of the land itself. This perhaps is the key. All nations are illusions, based on myths that more often than not rest on the lifestyle of societal elites. If you ever have occasion to ‘lie back and think of England’, what is it that you are supposed to think of? Ale in a country pub, cream tea on a neatly cut lawn, rolling green hills in an August sunshine? This is nothing more than an illusion, promoted by those who want to protect what they have. It is a myth propagated now by UKIP, reinforced in every photo of Nigel Farage raising a pint outside a pub. It excludes the vast majority of the population who cannot participate in this illusion, this false sense of ‘Englishness’. Is that really how we want to bind ourselves together as a nation? We should aim instead for a sense of nationality based in the landscapes of the islands which are, whatever our backgrounds, our homes now. We do not need UKIP or Nigel Farage to tell us what being English means, nor do we need to define ourselves against others. The poet Edward Thomas, on being asked why he was prepared to fight in the First World War, bent down, grasped a clump of earth in his hand, and answered “Literally, for this.” This “blessed plot”, this England, this is big enough to host any culture or ethnicity, as it has done since the beginning of time.