Painting for Bread – In conversation with Hockney, Utermohlen, Blake and Unsworth

by Christian Digby Firth | March 21, 2015

“Him? Oh he’s an artist.” You switch off and find another drink if that’s the answer to your curiosity about the stranger in the corner. People do; like if he was a bankmanager or an adman or a poodle parlour proprietor they’d know him backwards down to the brand of his after-shave and further. But an artist? – schmartist. Dirty habits probably, a welfare state sponger, drugs, demos. But wait – that can’t be his new Jag he’s driving away can it? What does he do – forge old masters in gold leaf? Or maybe you have the thing wrong from the other side, looking for a Croesus of the canvas inside the nearest pair of paint-stained jeans. Finding instead a paint-by-numbers hack living on cornflakes.

One way or the other, people don’t have the first idea of what a painter does all day – bar painting, if that – to keep his inspiration from the breadline where it doesn’t work so well. The reason he doesn’t know is that there aren’t any famous painters nowadays; there are famous people who paint, but there aren’t famous painters. The Glossies have taken care of that. Their reaction level is about as delicate as those machines you zap with a sledgehammer to test your muscles, and only a PR rating of a zillion will ring the bell.

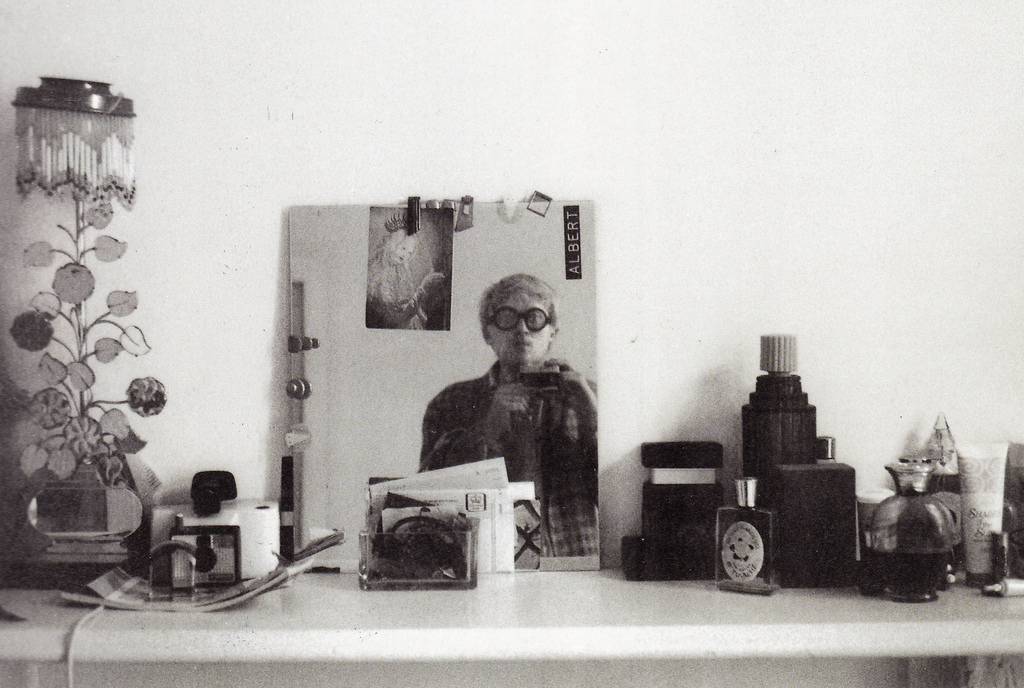

David Hockney is one of these feature-writers’ evergreens, which he doesn’t mind admitting since he’s also one of the best painters around. If anyone has made it, he has; the blonde hair and black frame glasses are everywhere, a genius-with-humour package for the editor who has everything. He lives at a shabby Notting Hill address, right past the Shelter exhibition home, but once inside you can see why he didn’t move. The rooms are huge, with great windows shedding in light; in one his latest work awaits completion for the major Whitechapel show. Another is like a Hockney interior — a hint of thirties furniture and a view of grey buildings in the windows. In person he’s less wary of the journalist than he’s entitled to be and uses his north-country equanimity to effect. We started talking about money. First off, he makes next to nothing out of that well-loved image; for example, Vogue recently paid £50 for a full page portrait, and for a week’s work by a painter of his reputation that’s a very good deal for them. “I got interested and spent quite a lot of time on it. They just wanted a page filled. I get asked to do a lot of things like that, and I do some of them.” It’s hard work that earns the bread. And through painting alone, Hockney has hit the big time. He’s never looked back. Even before he left the Royal College of Art the Kasmin gallery was selling his work on the strength of the Young Contemporaries exhibitions, and he started his post-college years on a contract which gave him around £1000 a year, guaranteed. Since then — 1962 — his fame has snowballed — RCA gold medal, graphics prize at the Paris Biennale, half-a-dozen one-man shows here, New York, Milan, countless group exhibitions, works bought by the Tate, Arts Council, V and A, Museum of Modern Art, New York, and with success has come the money; he turns over £10,000 a year now, painting about ten pictures in that time — all with a guaranteed sale. The rise has been almost too smooth for him to realise its pace.

‘There weren’t really any hard times, with my pictures selling at college. I just went on painting.” If he worked harder he could earn much more, but “I enjoy being myself and doing what I like. And being able to turn down jobs I don’t want to do.” For him that is the real value of his success.

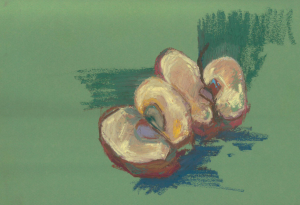

Hockney has risen like a fireball and burns brightly; this the only way to dine out on paint? Bill Utermohlen couldn’t be more different, live more differently – except he too gets people to pay him for what he likes doing. His Highgate house is beautiful and hung with his paintings, which are surreal, heavy with pattern and intense colour, and eloquent of a superb technical accomplishment. An American, he has studied in Pennsylvania and here and the Ruskin and the Slade, and has settled here with an English wife. He can’t afford the throwaway attitude Hockney now has to his meteoric rise; he didn’t ride the crest of a wave to a golden future – he swam the hard way with times when the undertow seemed to be moving backwards. For a start there was not teaching available in the States when he left college – a common problem there and here – and he took on any job, saving hard. In 1962 he married, but it wasn’t until ’64, with 300 dollars left that he got his fist exhibition and the show was tentatively on the road. Now in his thirties, with one-man and group shows in New York, London and Amsterdam behind him, a reasonably secure £1000 or so a year and a growing reputation, he still looks back on the first half-dozen years as the tough ones. “It’s a question of self-discipline and work. The successful painter is the one who can spend his time painting. I’m not a fashionable painter, but apart from teaching two nights a week my time’s my own.” A modest objective, hard-won.

Peter Unsworth lives with his wife and two children in a council studio flat – yes, a council studio flat, one of Westminster and Chelsea’s better ideas. At first sight he might be almost any successful man who spends his day doing a solid job of work – and of course he is and does; I was reminded of Utermohlen’s definition, “a successful artist is one who can spend his time painting”. And it really is as simple as that; he teaches two days a week for which he is paid £24 and paints the rest of the time – disturbing, charged landscapes in which vague figures are arrested in obscure motion. His last two shows at the Piccadilly gallery were sold out and another is due this year. The gallery fives him a substantial advance on each exhibition and, like Hockney, the main income limit is imposed by his confessedly slow output. The paintings, highly finished and of impressive technical competence, are a witness to this. Economically the set-up is just like many another small production businesses, the only difference being that you can’t double the night shift to meet increasing demand. Isn’t there perhaps the danger that those who reach the break-even point and further do so by their business acumen rather than artistic merit? No, because “the stamina required to trudge Bond Street is the same as that concerned with painting well.” Again, these had been Bill Utermohlen’s words, that the prime issue was of self-discipline, a sine even more qua non than money. Clearly their early lives both exhibited this quality from the start recognising that a desire to paint by no means qualified them for a free living. Peter Unsworth’s training was broken by military service, which he enjoyed, but he went back to St Martin’s College and got a National Diploma of Design. Then for four years he worked and painted in a systematic way – four months on, four months off; modelling (brawny cigarette ads), teaching, “anything”. In 1964 the Piccadilly were interested enough to put down an advance, and in the following year came the young painter’s Confirmation – a first show. It sold three-quarters. Since then he has justly considered himself to be living off his painting.

Peter Blake is a comfortably dressed man, bearded and almost jolly, but with something steely in his eyes. We met during a break from selecting RCA entrants. The shuffling feet in the corridors belonged to future Blakes and Hockneys, and their mouths would need feeding. Was this – the money facts of life – a prime obstacle to the painter? “Not really … the problems get worse as you go on. It was a question of egg and chips for supper then; I’m more aware now than earlier of choices.” Not the complaint of the destitute. Blake divides his income into three sources: commissions, teaching and his own painting. During the last year he reckons the painting could now support him alone if he wanted it to, which he doesn’t. I asked him how he had got to this position, and the answer was emphatic: “Patience, time and skill – these three have put me in an unique position as an artist. The price of my paintings reflects, if nothing else, the time spent on them.” Certainly he’s had little help from the establishment – incredibly the Tate bought their first Blake only a few months ago. Instead like Hockney, he’s ridden a wave; with him, he won a junior John Moores Prize in Liverpool in 1961, and in the same year got caught up with Ken Russell’s archetypal film, Pop Goes the Easel. And as credentials for the pop generation, a feature in the first colour supplement beats the lot. “I expect all this causes a little envy. Yes, I suppose I am seen as a cult figure… trendy.” He seemed a little bemused by the thought, charmingly innocent of the gobbledegook pop myths that lurk behind him. He’s married, with a child, a car and a house on which he’s just spent a tidy sum. In his thirties, he is appreciably richer than he would be as a successful businessman; the money buys time – the third of his ingredients for success. The patience and skill are on the house.

For these four, then, money has a smaller and less ugly head, if it is rearing it at all, than might be expected. The pessimistic assumption that nothing’s free, least of all a life of painting and enjoying it, is not wholly justified. One way or another they have all made it. At thirty-odd, the artist who is still working is secure enough to have overcome, even forgotten, his earlier problems. There seemed to be little or no sympathy for suggestions that the young painter could be given help; I had been putting forward ideas of some kind of subsidy to David Hockney: “not interested. The image of the hungry painter in Earls Court just doesn’t seem real to me.” He declared a faith that most painters have in the selection of the fittest: “I think painting still sells on its merits.” His own success clearly makes such faith hard to refute. Bill Utermohlen came up the hard way and is more concerned with the early years. But he too rejects any outright subsidy: “If my work had to be judged by ‘successful’ painters, I wouldn’t get the grant, I’m opposed to a jury system – how can it ever be fair?” Well, obviously it can’t until someone has decided which is “good” art – and therefore deserving of aid – and which isn’t, and the day that happens artists will be hopeless amateurs bumming jobs at the national institute of Beauty and Truth. Until then, we have to believe in the way things are, the vague movements which organise the hierarchy of fame and money; Blake does. “I had great difficulties at first, and I’m glad I had no help. I don’t believe in the welfare state. If you’re a failure it’s because you are a bad painter. Anyway money is crucial to only a small proportion of artists. I’ve always taken gambles.”

Hard words, these, from men who are out of the rough, but the message seems to be that it’s never as bad as the scenario writers would have it. Starving in garrets is out as an occupational hazard, teaching, commercial art and a brisk trade in pictures is in. The artists themselves, and who should know better, consider that the best man still wins.

May 4th 1970

Photo by Playing Futures: Applied Nomadology