The Lost Children

by Tom Gardner | January 16, 2012

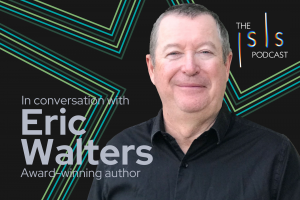

Restavec is a Creole word meaning, literally, ‘one who stays with’. It is also the term for a Haitian child who is abandoned by their family to a childhood of servitude in other households.Until very recently, this Haitian practice was virtually unknown to the outside world, and has only now been condemned as a modern form of slavery by the UN. UNICEF estimates that, on an island with a population of just 8 million, 300,000 children work as restavecs. Twenty years ago, the UN paid almost no attention to the issue, and had only a dim awareness that these restavecs even existed. After four speeches to the UN Assembly, two books, and tireless campaigning both in and outside of Haiti, it is no exaggeration to say that Jean-Robert Cadet is the man who put the Haitian restavecs on the map. A former child slave himself, Jean-Robert Cadet’s life story is, in part, one of violence and neglect at the hands of his former ‘owners’, of constant struggle against oppression and injustice. Yet it is ultimately one of catharsis, as his journey sees him cross, as he puts it, the seemingly unassailable gulf from “Haitian slave child to middle-class American”.

Jean Robert Cadet sits across from me in an unassuming service station on the M4. He wears a baseball cap and, and in his soft French-Caribbean accent he speaks confidently and candidly of his time as an abused and unpaid domestic servant throughout the first fifteen years of his life. He states bluntly: “I did not have a childhood.” The illegitimate product of his wealthy white father’s philandering with his maid, Cadet was sent as a restavec to stay with a high-class prostitute (known under the pseudonym of ‘Florence’) whose clients included numerous government officials. In her care he was treated like the thousands of other Haitian children deemed socially unacceptable, and was subjected to physical and emotional abuse.‘Florence’ pulled and pinched his penis, beat him in his sleep, kicked him with her high-heels, forced his head down the toilet, made him wash her blood-stained menstrual rags.

However, it was the emotional and verbal abuse, Cadet confides, that left considerably deeper and longer-lasting scars. Florence called him a dog, told him he would never amount to anything more than a ‘shoeshine boy’ and, by making him sleep on the kitchen floor and forbidding him ever to sit at the dinner table with the rest of the household, ensured that Cadet would be unable to endure almost any social situation for decades after he finally left her. It is this lasting psychological and social damage, so acutely described in his first book Restavec, which make his poise and ease so remarkable.

As a restavec, Cadet was made to believe that he was worthless. “In Haiti, sleeping in a bed means that you are somebody,” he explains. “I never had a bed; I slept under the kitchen table… I believed I was not worthy of a bed.” He was the victim of a fragmented society in which “everybody wants somebody underneath them… all the way down to dogs.”Cadet harbours few doubts as to where the blame for this fragmentation lies. “The French,” he answers firmly, Haiti’s former colonial masters. Cadet explains that France, along with other colonial powers, were responsible not only for ‘quarantining’ Haiti after the independence in 1804, but also for imposing rigid social hierarchies on Haitian society, hierarchies capable of perpetuating slavery long after the French had left.

Understandably, Cadet has little time for those who question whether the restavec system really constitutes slavery in the strict sense: “Restavecs are treated worse than slaves,” he says unequivocally. He is similarly brusque about claims, particularly those of his fellow Haitians, that this tradition is best understood as an underground foster care system, rather than a system of slavery. “Haitians are proud of their history”, he explains. “As the descendants of former slaves, most are unwilling to believe that they could have become slave-masters themselves.” Even those at the very top of Haitian society are complicit in this culture. Cadet explains that the Chief of Police also holds children in servitude. In a society in which vast extended families are the norm, it is easy for people like this Chief of Police to have a ‘niece of his wife’ living in his household, being treated, whether they acknowledge it or not, as more of a slave than a member of the family. The subtleties involved in this mean that it is often difficult for people and organisations unacquainted with the culture, such as UNICEF, to identify which child is a normal family member, and which is a restavec. For this reason, it is easy for some to deny that restavecs are treated badly, with many arguing that the system is a form of social welfare similar to those seen in other countries; a way of helping a child from a poor family.

Cadet is dismissive of this. “The difference is the brutality,” he argues. “Many countries are very poor, and many may have similar systems, but the Haitian system is unique in its cruelty.” For Cadet, the reasons behind this are cultural; it is no use simply blaming poverty and assuming that the practice will disappear as GDP grows. Failing to value the sanctity of childhood is, according to Cadet, deeply ingrained in the country’s social fabric: “it is part of their cultural make-up dating back to colonial rule”. He explains that the Haitian language is rich in proverbs such as ‘a child is like an animal,’ and as such, the problem is a one of attitude and perception, rather than of material deprivation.This perhaps explains the prevalence of the system at all levels of Haitian society, and the lack of remorse on the part of Cadet’s former keeper Florence: “she felt no need to apologise. She didn’t think she had done anything wrong. She did what she did because someone before her had done the same.”

Cadet, unlike most of his fellow restavec children, was fortunate in that he was educated. He does not accept that this had anything to do with luck, however. “It was a matter of convenience,” he explains. “When a visitor would come round and I answered the door, I was expected to write the name of the visitor down for Florence when she returned home. If I couldn’t write the name down, then I was useless. That’s why they sent me to a literacy centre.” For most restavec children, education is not a possibility, but Cadet is insistent that this is the key to eroding this culture of slavery and abuse. An effective state education, and an education which instils Haitian children with the values of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ are what matters.The UN troops propping up the weak government are not the solution, nor are the NGOs, which, he says, are exploitative in their own way: “NGOs use the issue to make a living. Their programmes are not working.”

But if education is the most viable route towards a restavec-free future for Haiti, the 2010 earthquake certainly hampered its progress. Not only are the country’s institutions and infrastructure in tatters, but the number of restavecs has risen considerably. Prospects look bleak, but there is certainly still hope. The first step is in the work of people like Cadet; people who decide to tell their stories rather than stay silent.

——–

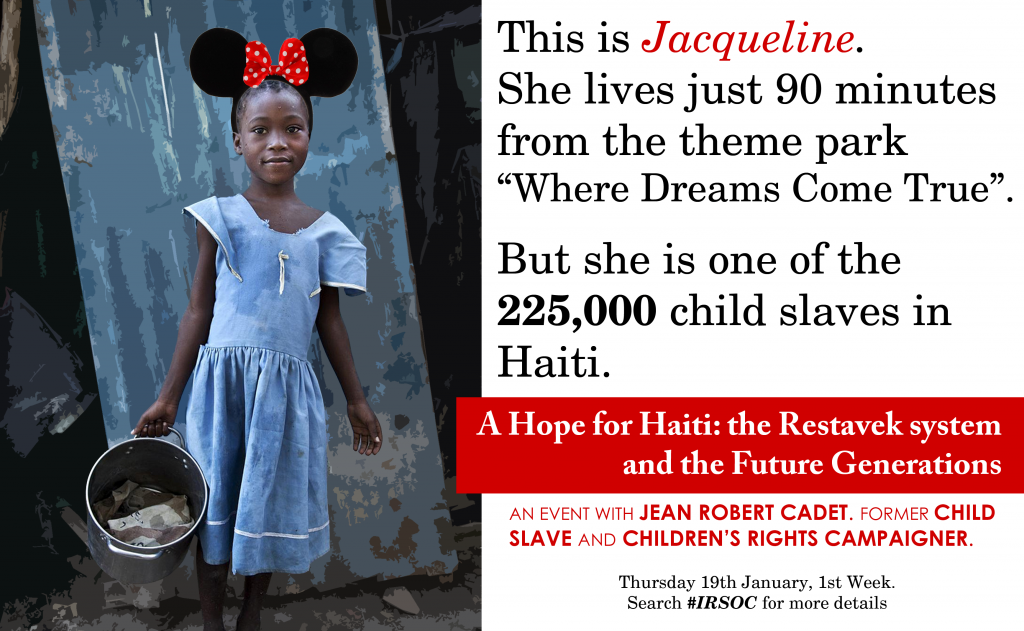

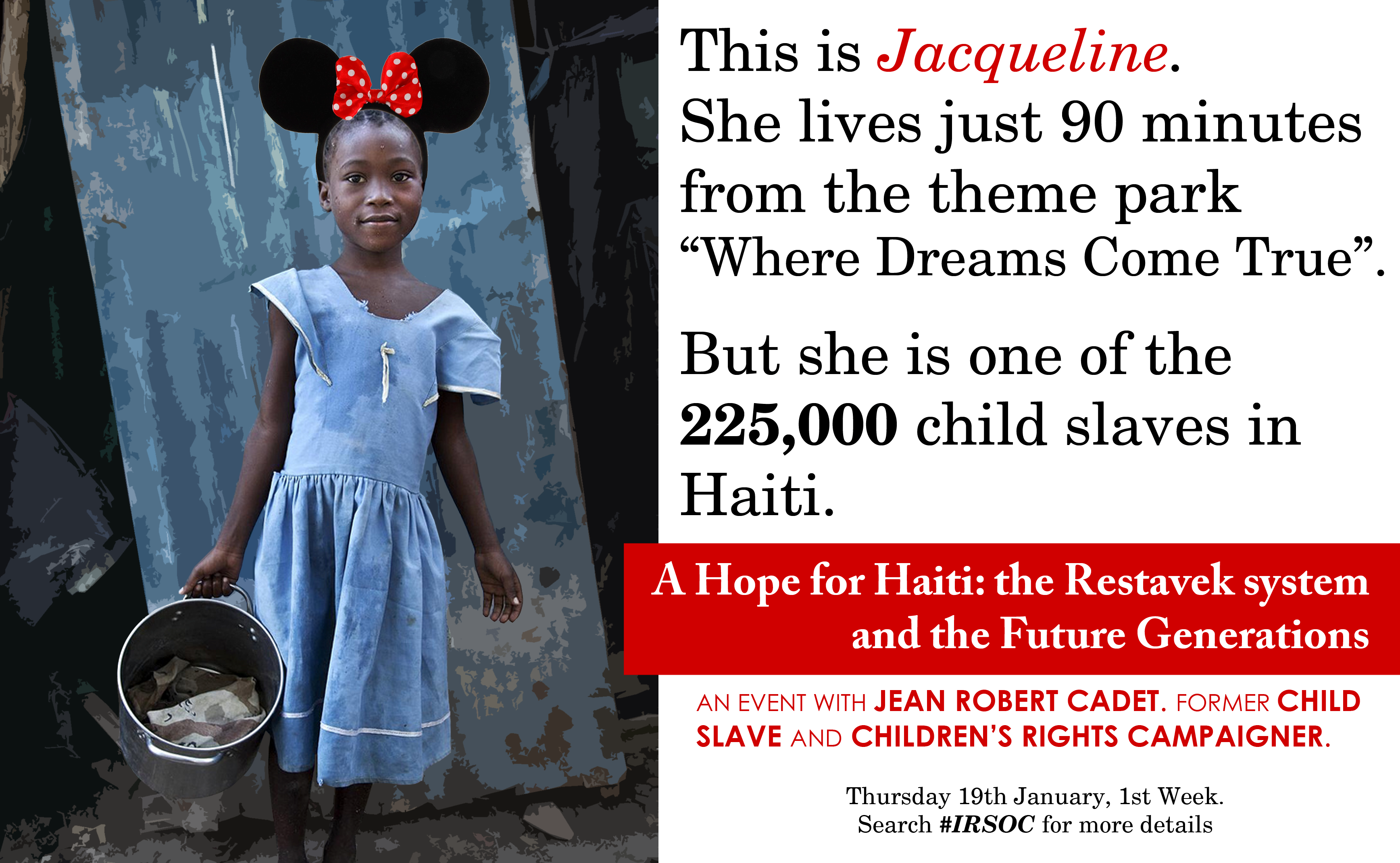

Jean Robert Cadet will be speaking on “A hope for Haiti – The restavek system and the future generations” with the International Relations Society on Thursday 19th January, 7.30pm, at Queens College, Lecture Room B