We must not forget them…

As you cross the border from Chile to Argentina, a vast billboard reads, “The Falklands are Argentine”. Before even entering the country it is made indisputably clear that the 1982 war is very much at the forefront of people’s minds. It’s never long before a travelling Brit is asked the pointed question, “so what do you think about the Falklands?”

Every major Argentine city has a permanent demonstration, where groups of veterans hold vigil over large maps of the Falklands in Argentina’s blue and white stripes. The signs declare, “We must not forget them. They are non-negotiable.”

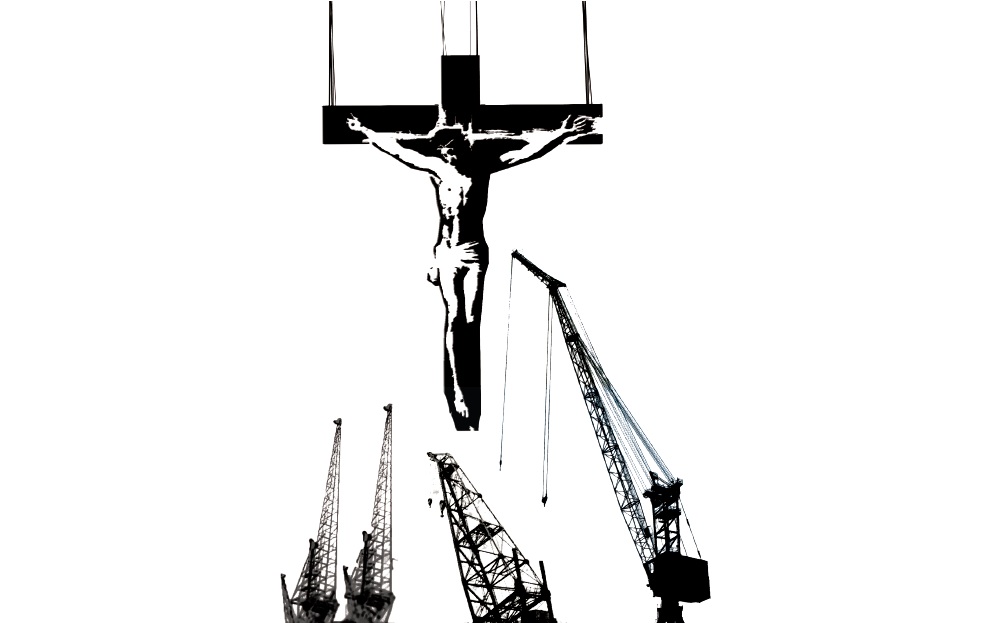

The Monumento a Los Caídos en Las Malvinas (Monument To Those Who Fell In The Falklands) has pride of place in the capital. Here, the names of thousands of victims are picked out in gleaming plaques, and a perpetual flame burns over an image of the islands. The monument is guarded in two-week shifts by the three main branches of the Argentine armed forces – the Army, Navy and Air Force – with an elaborate changing of the guard ceremony that draws tourists and civilians alike. It stands in perpetual confrontation with the Torre Monumental, a building formerly known as the British Clock Tower, and a gift from British citizens.

In stark contrast, many British people perceive the Falklands merely as a distant, unprepossessing collection of islands with an inhospitable climate. There is no monument or war memorial for the Falklands in Britain, nor a public holiday, as Falkland War veterans are commemorated only as part of Remembrance Sunday.

Nearly thirty years on from the war, there are few Brits not directly involved with the conflict who feel particularly strongly about whether the islands remain British or not.

So why is it that Argentina’s claim to the islands has continued to pervade public opinion, whereas in Britain the windy overseas territory is largely forgotten?

Thirty years ago, the Falkland islands were on British people’s minds and tongues just as much as they are today in Argentina, with Thatcher’s 1983 election victory largely due to her success in preserving the territory as British. Sovereignty over the islands germinated a wave of patriotic sentiment in both countries. The difference is that Argentina has retained what appears to be a largely visceral claim to the islands, whereas for Britain that once-uniting issue has fallen into relative insignificance.

“The Kirchner administration will more than likely look to keep the Falklands issue on the front pages,” says Dr Matt Benwell from the University of Liverpool, who has research interests in the Falklands (or Malvinas as they’re known in Argentina) sovereignty question and more specifically the perspectives of Argentine and Falkland Islander youth. “Argentine politicians often use the Malvinas issue as a rallying call to unite the people.”

Every school displays a poster explaining how the British usurped the islands

Unlike many youngsters in Britain, Argentina’s youth are far from disengaged with the Falklands question. For many of them the Malvinas are unquestionably Argentine – their presence in the classroom ensures that. Every school displays a poster explaining how the British usurped the islands, picturing the dark blue vein of the sea dipping suddenly to the right to include the Falklands in Argentina’s territorial waters.

“Argentina’s youth maintains a strong connection with the struggle for the Falklands, manifesting itself particularly in social networking sites,” says Pablo Ruiz Diaz of the most popular web forum for discussion of the conflict, Islas Malvinas Online. “35% of active users on my site are under 25 years old, a figure that is in no way inconsiderable if we take into account that the war took place almost thirty years ago. This figure grows to 63% if we include the group of 25-34 year olds.”

These statistics are even more startling when compared with the debate coming from the other side of the Atlantic. One Facebook group arguing “Malvinas son Argentinas” (“The Falklands are Argentine”) has over 300,000 members, whilst its equivalent rival, “The Falklands are British” has a mere 369 members. While thousands of similar groups exist hailing Argentina’s right to the islands, the few British groups that appear each have only a handful of members, uttering occasional rallying cries against the Argentine enemy.

There is no question then that the level of youth engagement with the issue in Argentina remains high. However, Dr Benwell’s research suggests that politicians’ use of Falklands as a vehicle for political point scoring, assuming the ability to muster support at the mere mention of ‘Malvinas’, may now be futile. He has found that many young Argentines hold a sceptical view of the Falkland problem, questioning the timing of its appearance in the news, which often coincides with a political scandal elsewhere.

So why the continued support of the Argentine sovereignty claim? In a speech in June 2011, President Kirchner described Britain as a “crude colonial power in decline”. Written cries of “Long live Argentina!”, “The Falklands are, were, and always will be Argentina’s!” and “The empire is coming to an end. Argentines will be victorious!” flood the walls of the most popular pro-Argentine Facebook groups.

Evidently, there is concern that the British presence in, or occupation of, the Falkland Islands represents a relic of the colonial days that sits uncomfortably with 21st century Latin America. Yet this is somewhat ironic, given that the legal basis of Argentina’s claim to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands is due to their status as part of Argentina’s territory under Spanish imperial rule.

Argentines are found to be less worried about the question of sovereignty than the benefit of having the territories in terms of potential resources.

The islands’ relevance and the reason for all the powerful emotions they arouse are more subtle than sheer patriotism and anti-Imperialist rhetoric. Research shows that the motivation behind interest in the islands is multifaceted. Argentines are found to be less worried about the question of sovereignty than the benefit of having the territories in terms of potential resources.

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges claimed in a 1982 interview that “the Falklands thing was a fight between two bald men over a comb”. This may have had a grain of truth at the time, but since the more recent discovery of oil in the sea around the Falkland Islands, the “Falklands thing” can no longer be dismissed as a case of political one-upmanship. Tension is rising since British company Rockhopper Exploration discovered oil whilst drilling in the sea around the islands. Suddenly the debates have been renewed.

With the thirtieth anniversary of the conflict approaching, the number of war veterans dwindling and the public’s emotional attachment to the islands perhaps beginning to wane, suddenly there is a new reason for Argentina to be interested in the South Atlantic territories.

Recently, there has been speculation about Britain’s ability to win a repeat Falklands war

But so too for Britain. Recently, there has been speculation about Britain’s ability, given the recent cuts in defence spending, to win a repeat Falklands war. Admiral Sandy Woodward, Commander of the British Naval Force in the South Atlantic in 1982, wrote a controversial article in the Daily Mail claiming that without US support, and given our lack of aircraft carriers, there was no possibility that Britain could defend the Falklands today in the face of Argentine aggression. Although the Ministry of Defence later dismissed his claims as unsubstantiated, Admiral Woodward’s arguments fuelled renewed speculation over Britain’s ability to hold on the territory.

The Falkland Islanders themselves do not observe Argentina’s public holiday in remembrance of the soldiers who died in the Falklands, nor have they expressed a clear desire to be anything but British. It is on this basis that Britain refuses to involve itself in negotiations over sovereignty. In June David Cameron made a statement insisting that Britain would not hold negotiations on the islands’ sovereignty until the Falkland Islanders ask for them, “full stop, end of story”. Since the Falkland Islanders are the people who will be most affected by the discovery of oil in the South Atlantic, perhaps Cameron is right to consider them first and foremost – or perhaps their interests just conveniently coincide. It’s possible that, as British public interest is reignited, visitors will be greeted with placards proclaiming “The Falklands are British” as they step off the ferry at Dover.