The War On Secrets: A Weekend Inside the Wikileaks Machine

by Isabelle Fraser | December 6, 2010

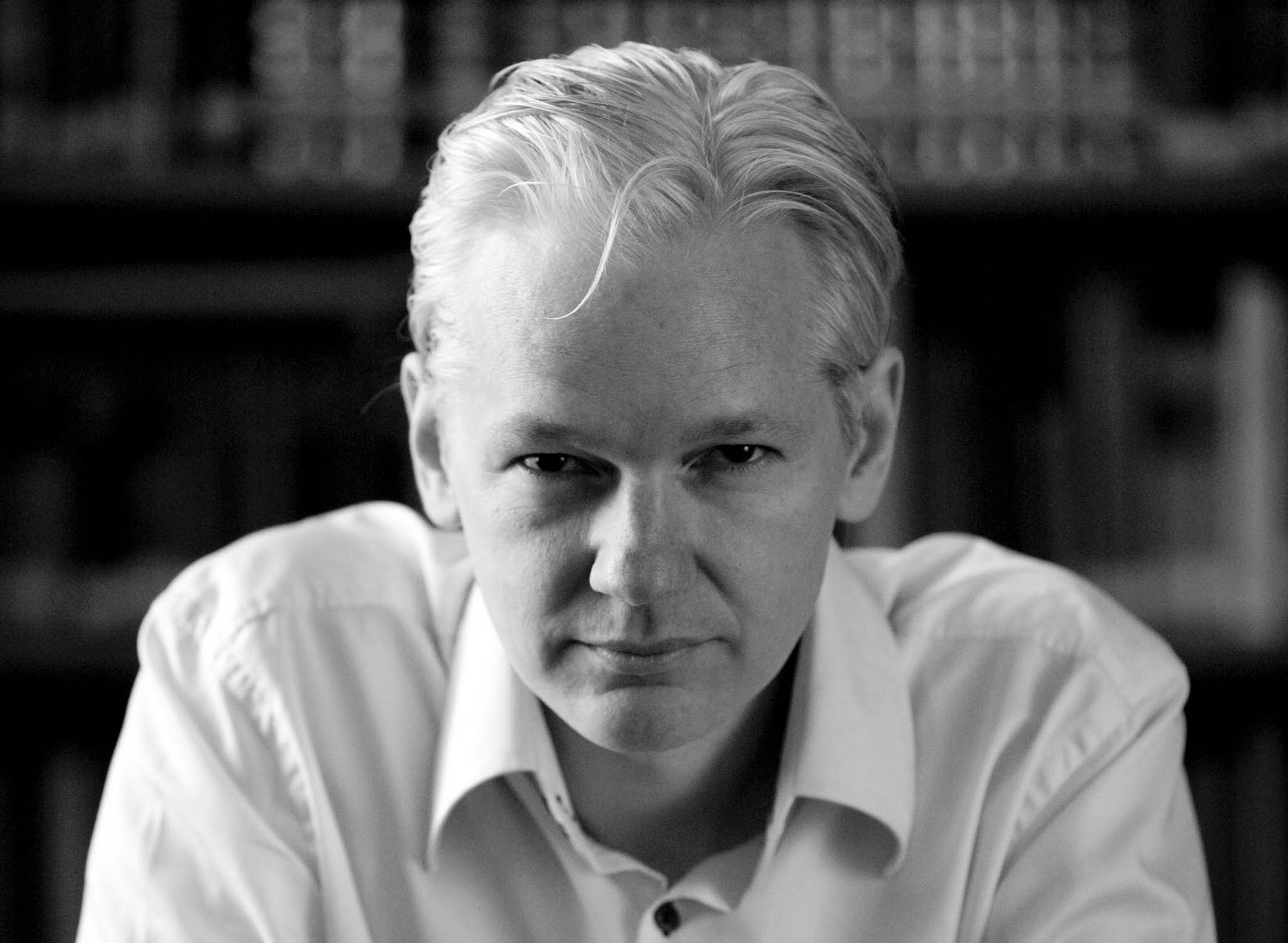

Julian Assange is sitting across the table from me, eyes fixed on his computer screen, searching for videos of himself. He is the one-man band that is WikiLeaks, the controversial organisation that publishes leaks that are anonymously sent to them.

Past leaks have included the BNP membership list; Sarah Palin’s Yahoo account; the report into Trafigura’s toxic dumping in the Ivory Coast that had been stopped by a ‘super-injunction’; and the video ‘Collateral Murder’ — classified US military footage showing 12 people being killed by US soldiers in a helicopter, including two Reuters journalists. It was this leak that propelled the organisation into the limelight, but the Afghan and Iraq War Logs of July and October respectively took the media glare into a whole new level, often making Assange the story, and not the leaks.

After pursuing the members of WikiLeaks, I was asked to intern for them on the weekend of the unveiling of the Iraq War Logs in October. I found myself in a Paddington office ringing up NGOs, other volunteers slogging through the list of the press that would be attending the press conference tomorrow. Everyone is an unpaid volunteer, and does it either because they believe in what WikiLeaks is doing, or because they are fascinated by the organisation and Assange, this strange, lanky Australian man. I was definitely with the latter. After the Afghan War Diary of 92,000 documents was released in July 2010, I was angry and confused. How could they release these unredacted documents, knowing they were putting informants’ lives at risk? Having met the man in charge, and seen the serious redaction of the most recent leak, I am still undecided.

As I arrived Julian had just come back from an interview with CNN that he had walked out of after they made reference to his personal troubles of rape allegations in Sweden. Later, we watch the video and he seems justified in his actions: while trying to talk about the 109,000 killed in Iraq, the reporter unfairly pushes questions surrounding his private life. And this seems to be a relentless problem; indeed, whenever I turn my dictaphone on he tenses up and changes from a relaxed, funny guy into his media persona, with a flat baritone voice, choosing his words with the utmost care.

Julian is very likeable, and disarming at times. He will stand unnervingly close and watch you, waiting for you to say something. He is a computer geek, who in his childhood, which he spent on the run with his mother in Australia, taught himself coding and hacking and has been described as having ‘exceptional skill’. He was a member of the hacking team the International Subversives, under the pseudonym Mendax, breaking entry into systems just to see if he could. He’s also quite sexy, and very confident; he gave me various pecks on the cheek throughout the weekend, and a bear hug as I departed on the last day. He’s like the Pied Piper, attracting followers who fawn over him on the internet and, if they’re lucky, in person.

The WikiLeaks organisation seems like a ramshackle affair, but one that works incredibly efficiently. Those that I met were the most visible members of the team, mainly dealing with the press or busy filming the whole operation; beneath the surface on the web are those dedicated volunteers who maintain servers and make sure that the website is secure and accessible. These are apparently the ‘high priesthood’ of the organisation, and without them it could not exist. WikiLeaks uses a complex system of servers in countries such as Belgium and Sweden, which has strict whistleblower laws to protect the anonymity of sources.

On the eve of the leaks, there are only 7 people in the office in London. Julian jokes at how the Pentagon has announced that they have 120 staffers ready to attack the coming document dump. The feeling around the table is that ‘they fucking hate us’. And it seems like quite an ‘us versus them’ atmosphere, 7 of us versus 120 of them, There are rumours abound of how ‘someone’ brought down one of WikiLeaks’ servers in the past week, Kristinn Hrafnsson, the spokesman said ‘I don’t believe in coincidence’. There are a lot of people out to get them. Julian ridiculed the Pentagon, who claimed they had seen the documents, and produced 9 names before the release despite it being redacted.

There is an air of tension among the WikiLeaks people that I meet. Many wonder whether they are being bugged or followed. When offered my internship I was told not to tell anyone about the weekend, or say where I was going. ‘Wendy’, an activist, hides herself and her computer with a blanket as she types in her password. A tech wizard who is helping out over the weekend tells me he keeps himself busy in order to stop thinking about the dangers involved in being a member of WikiLeaks, that he ‘lives in fear’. In a New Yorker article, Julian talked about having surveillance photos taken of him, and being followed. On the coat peg in the office hangs a full, grey wig, and apparently has a large selection of odd hats. Whether these are part of Julian’s disguises is unclear, but he is certainly a watched man.

Julian is a drifter, reportedly staying on people’s couches, never having a fixed address, mobile number or email address. An application for a Swedish residency permit has just been rejected, and he can only legally stay in the UK for six months He can’t go to America because he fears there is a secret warrant out for his arrest, and he can’t go home to Australia because they will comply with the Americans. The alleged source of the two latest leaks, PFC Bradley Manning, is currently imprisoned in a military base in Quantico, Virginia. WikiLeaks will never disclose the name of a source, even if they knew it. It is only with this anonymity that the organisation can attract such leaks. But if this is happening to him, then surely American agencies are looking to do the same to Julian. Supporters see the rape allegations in Sweden as part of a smear campaign, directed by the CIA or some other secret body. Some speculators on the internet have decided that WikiLeaks is a CIA front. Many on the Right have demanded that Julian should be treated as an ‘enemy combatant’, and called for ‘non-judicial action’ against him, in other words, send him to Guantánamo. The National Review, a conservative magazine in the US, asked the question: ‘Why isn’t Julian Assange dead?’

WikiLeaks not only faces threats from those who want to shut it down (dark government forces), or sue it (such as Scientologists after an embarassing leak). There are rumours of tension within the organisation – the spokesman Daniel Schmitt acrimoniously quit after disagreeing with Julian about how they should be focussing on smaller leaks rather than huge ones he deemed that were just for the publicity. The print media, which members of WikiLeaks have criticised for not doing their job properly, insists on biting the hand that feeds it. The New York Times was the only newspaper in America to receive early access to the documents, and then printed a hit-piece the day after, ‘full of errors, top to bottom’. It was a piece of gossipy journalism that has been widely criticised, talking about Julian’s private life and the seemingly fictional resignations of staff. There was also talk about how the Mudorch media empire was ‘pissed off’ at being left out of the leaks – none of the front pages were anything to do with the leaks.fd

Anger broke out in the office on the evening of the leak as an Al-Jazeera story broke the embargo by a whole hour and the internet was suddenly flooded, in a matter of minutes, by news stories of the leak. There were 100 tweets a minute, and a panic that the servers were not withstanding the weight of traffic: ‘we’re getting battered here’. It was extraordinary to see this tidal wave of information rush over the world and being at the source of it. Julian triumphantly declared ‘you’re watching history take place1’ Twenty minutes after, I headed to the chippie near the office to find a BBC news crew already going live with the story. The reporter was having an altercation with a drunk guy while simultaneously reporting on the story. I was eating my fish and chips. Five surreal hours after the embargo was lifted there were 1500 articles on the leaks, according to Google News.df

Their relationship with the media is a strange one. Kristinn Hrafnsson, the so-called ‘muscular Swede’ told me that ‘in the best of worlds, WikiLeaks would be an unnecessary organisation. It might possibly be the utopian aim of WikiLeaks to make itself totally redundant.’ Kristinn described what they did as ‘raw journalism’, and an early ideal of the organisation would, according to the former spokesman, ‘create a revolutionary spirit… of digging out the dirt on governments.’ They see themselves as investigative journalists, doing what regular journalists can’t or won’t. And they forensically research the documents they leak, getting specialists to help ascertain their authenticity. Julian told me that the ultimate purpose of WikiLeaks was ‘to promote justice around the world’.

This is a noble aim, and much more lofty than what the press conference descended to, as a scum of cameras of the world’s press surrounded the main man. The purpose of the press conference, citing the deaths of 109,000 people, seemed strangely at odds with the plush swirly carpets of a riverbank hotel. While handling press interviews and queries, it struck me how stupid some journalists were. An example:

“I want to see the documents”

“They’re online”

“No, I want you to give them to me printed out”

“But there are 400,000 reports”

Daniel Ellsberg, the leaker of the Pentagon Papers of 1971 and a legend of the whistleblowing community, spoke about his admiration for WikiLeaks, and seemed to treat Julian as if he were his proud father, passing on a trade. Julian appeared quiet, and almost boring while speaking; as if he wanted to deflect attention off himself. He has said in the past that ‘we always expect tremendous criticism. It is my role to be the lightning rod … to attract the attacks against the organization for our work, and that is a difficult role. On the other hand, I get undue credit.’ Offstage, and upstairs waiting to be interviewed, Kristinn and Julian tucked into BLTs. Julian switched back from his media persona into the curious, confident and gregarious person he is naturally.

But when I come down to asking him about the thing that troubles me the most about Wikileaks, its secrecy and undue power, he becomes evasive and spins jargon, particularly about ‘harm minimization’. ‘That harm minimisation process is designed to strip the harm from the document and maximize the benefit…’ For an organisation whose aim is to ‘open governments’ and encourage transparency, they are quite opaque about their dealings. Their coverage this time around was more favourable than with the Afghan leak because they took care to seriously redact the data, starting by redacting everything and working backwards. After the Afghan War Logs, Julian declared, chillingly, ‘I’m not scared to make mistakes or be blamed, or even accidentally cause harm in the cause of justice.

This recklessness, as well as the editorialising of the ‘Collateral Murder’ video has diluted the power of WikiLeaks. The care taken over the new leaks is surely a PR exercise, to push the perception that they are responsible with the data that they publish. Kristinn told me that ‘we still have some material coming… [The fallout] is going to be spread over a long time. And it’s got a different tone, there is more emphasis on the material than the story being the leak.’ Whether Julian will ever stop being the centre of attention is doubtful, but it will take a lot to bring down WikiLeaks.

d