Unity in the Face of Imminent Climate Collapse

by Jacob Harrison | June 13, 2019

Roger Hallam is a wiry man – slim but tough. He has dark eyebrows, eyes sunk deep in their sockets, and wisps of hair either side of his face. He’s married, a father. What stands out the most though, when he starts to speak, is that somewhere – not too far beneath the surface – he’s furious. He has an edge of mania. You can see a tense frustration tugging at the lines of his face.

“People have a very Marie Antoinette relationship with the world, with the climate,” he says. “You know, ‘let them eat cake.’ They think it’s happening to someone else.”

Fifteen years ago, he owned one of the largest organic vegetable businesses in the UK. He knew about climate change then. He’d known about it since the 90s like everyone else but he’d never really acted on it.

Naomi Klein, in the now-legendary This Changes Everything, calls this kind of behaviour ‘looking away.’ It is a refusal to acknowledge the severity of the problem that is climate change. It is making a small, token gesture in order to feel as if you’re doing your part. Using paper straws or a reusable cup – that’s looking away. Making sure you recycle is looking away. Giving up meat is looking away. Hallam, like the rest of us, was looking away. Until one fateful summer when it rained every day for seven weeks and his crop, hundreds of thousands of pounds worth, rotted. His business folded.

For Hallam, suddenly it wasn’t happening to someone else; it was happening to him. It made him furious. Furious that the situation had deteriorated so extensively, that no one in our systems of governance, control, and regulation seemed to be doing anything to try and stop it. Furious – and he doesn’t say this explicitly, but it is there – at himself; at the part he played in the collective negligence that has come to embody the global response to climate change.

It’s clear that the anger began to fuel him. After the demise of his farming business, he decided it was time to stop looking away and do something. He did a doctoral degree at King’s College, London. His thesis analysed radical nonviolent protest movements over the last century, from the Indian independence struggle led by Gandhi to the US civil rights movement. It was not the issues that drove his interest (although it’s clear that these causes matter to him deeply), but rather the reasons these movements were successful.

“It was a manual for changing the system,” he says. A kind of ‘how-to’ for revolutionaries. His conclusions are startlingly simple. “Violence is bollocks. If you look at the history, it doesn’t work. Nonviolent civil disobedience is the method that works. It’s science.” He lives by these very principles: in 2017, he went on hunger strike in an attempt to get King’s College to divest their investments in fossil fuels. After 14 days with no food or water, his protest succeeded. For a while, he travelled the country giving talks to groups who wanted to stage successful protests. A mercenary in the revolution-crafting business.

Sometimes, sheer force of will can initiate change. Somewhere along the way, these experiences were knit together; all the frustration and sense of loss, the deep-seated belief in nonviolent direct action and, most of all, the disenchantment with the current political class and the failure of our socio-economic system. What emerged was ‘Extinction Rebellion.’ Say it out loud. Listen to it. You can hear the anger. The seven syllables rush out one after the other in a frantic attempt to communicate an uncomfortable message. The sharp syllables of Extinction – complete destruction, the extinguishing of all life as we know it, darkness. The fiery timelessness of Rebellion – upheaval, the changing of systems, the unknown. Greenpeace, founded fifty years earlier, suddenly sounds very tame indeed.

In many ways, George Monbiot couldn’t be more different to Roger Hallam. Straight after graduating from Oxford with a degree in Zoology, Monbiot became a documentary maker. He travelled far and wide, chronicling the breakdown of ecosystems from Brazil to Tanzania. The way he tells them, his travels sound somewhat Odyssean: Monbiot has been shipwrecked, shot at, and stabbed through the foot with a metal spike. He is banned from seven countries and was sentenced to life in prison in absentia in Indonesia. He attempted to perform a citizen’s arrest on US ambassador John Bolton for his role in the Iraq War, co-founded the Respect Party, and even had time to record a very successful folk album along the way.

In spite of all this, Monbiot exudes none of the same mania as Hallam. He is almost infectiously calm and unhurried, especially for a man who churns out several articles a week for The Guardian, organises nationwide protests, and looks after his two young children. On the day of our interview, he would go on to tell an excited crowd of children at the Youth4Climate School Strike that they were “the most beautiful thing” he had seen in several decades of environmental campaigning. Still, his optimism is measured: “‘Happy’ would be a grotesque exaggeration – I have a gem of hope which wasn’t there before.”

Monbiot may well be softly-spoken, but he is a troublemaker just like Hallam; one who came from inside the establishment. “There was only one job I wanted to do and that was to make investigative environmental programs.” He did this at the BBC for several years, but with little success: “There was a fatwa against environmental coverage. Time and time again, we were told: no environmental programs.”

Like Hallam, Monbiot’s frustration culminated in an epiphany – you can still trace the shock in his voice today. This wasn’t just individuals looking away, there was an ingrained bias against covering climate change at the largest broadcasting organisation in the world. Environmentalism was, in Monbiot’s own words: “the skull at the feast.” These two men are bound together by their shared reaction against the framework for looking away.

How has this changed in 2019? What of the excitement galvanised by movements like Extinction Rebellion (XR) and the School Strike for Climate? Is this the year where the climate finally embeds itself in the public consciousness, sitting firmly at the top of our to-do list? Monbiot nods vigorously. We’ve finally broken the deadlock. “I’d struggled for years to get any sort of readership. People really didn’t want to know.” Now Monbiot’s environmental articles are almost always his most read pieces; his speeches at demonstrations receive raucous applause and gain millions of views online. At the moment, he is arguably the most prolific voice backing rebellion through nonviolent direct action and, crucially, was one of the first to emphasise the importance of young people’s participation. “Young people aren’t putting up with it anymore. They’re not putting up with the denial, the indifference – this cannibal culture we’ve developed where the old eat the lives of the young. They see this is the last chance we’ve got and they are determined to take action.”

XR has become a lightning rod for a new wave of activism. University professors in Bristol were arrested for spray painting public buildings with the group’s logo. Children as young as 14 attempted to blockade roads to terminals at Heathrow Airport. There have been two open letters, signed by more than 200 academics, criticising the government for the way in which it has handled what XR was one of the first to call the ‘climate emergency.’ This shift in language is typical of XR tactics. ‘Rebel for life’ is another example of their deft use of language, and Monbiot, like many activists, repeatedly refers to the destruction of our ‘life support systems.’ Their lexicon reflects the urgency that Hallam exudes – and it works. Parliament declared a nationwide ‘climate emergency’ just months after activists coined the term.

XR heralds a new era for environmental activism. It is the first group in decades to consistently bind together thousands of people from outside the ‘activist scene.’ What’s more, XR successfully rallied them to take part in direct action, risking arrest and even prosecution for their activism. Monbiot views the richness of XR’s composition as underpinning its success: “Some of the people involved are veteran campaigners, whereas the majority are very young people, some in their early teens and already highly articulate in putting forward the environmental case. We have that great combination of experience and determination.”

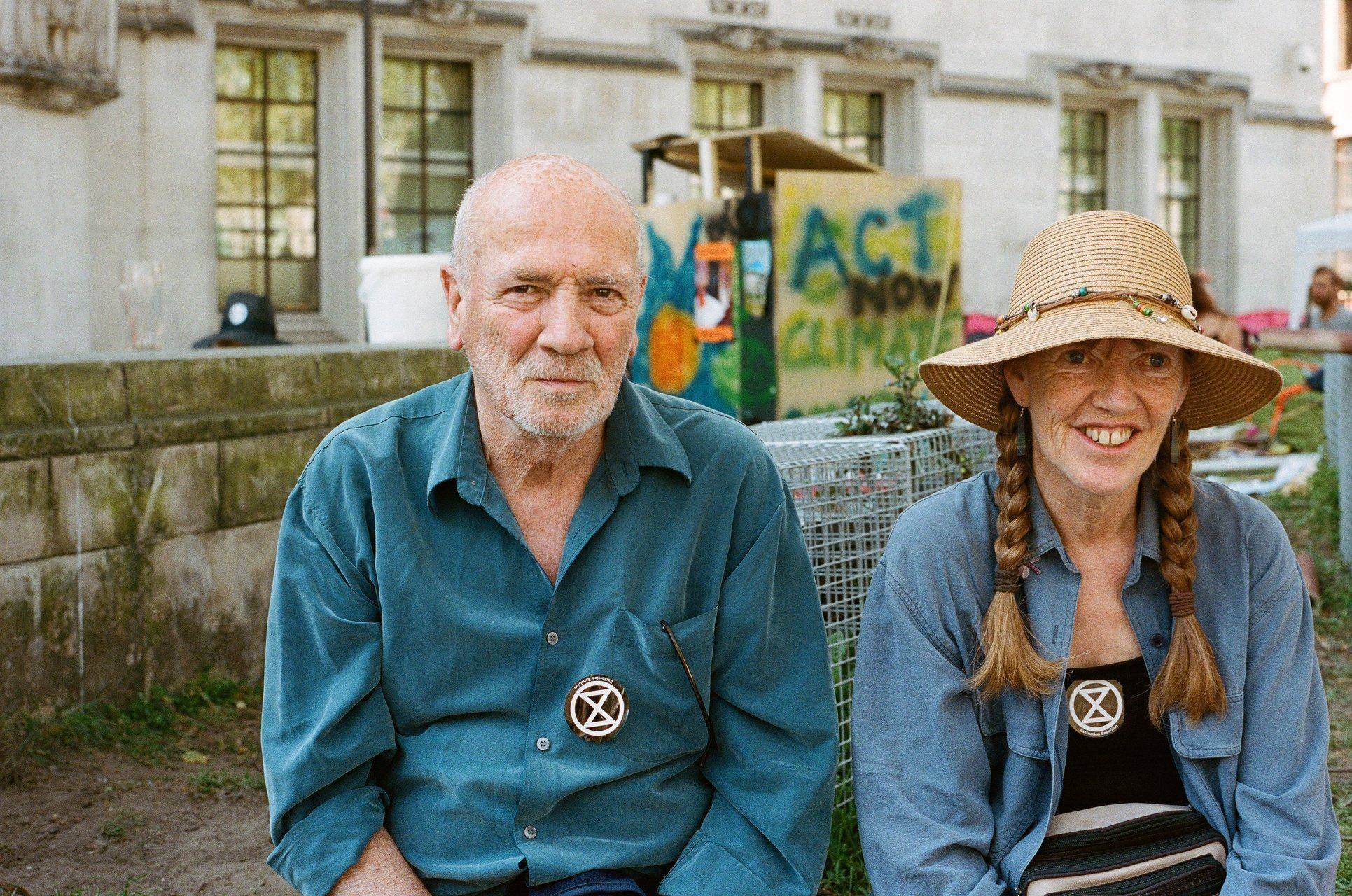

Take Mary and Bob: they are sitting on a low wall in Parliament Square, soaking up the April sun. Mary wears a broad brown sun hat and both sport distinctive XR badges. They must be in their seventies. “I’ve never been to a protest before,” Bob says. “But Mary is a veteran of Greenham Common [a renowned anti-nuclear arms peace camp established in the 1980s]. We’ve got a bit of the fence in our bedroom.” Though there is a sense of resignation, they’re not angry. They’re not driven by hatred of or frustration with the system as Hallam and Monbiot are.

Instead, Mary says she’s here for their four grandchildren: “Nearly four, nearly five, nearly eight and nearly ten,” she rattles off. They feel it is their responsibility to participate for the sake of those who will come after them. They believe in XR’s principles, Mary says, but they are just here for the day. Unlike in some other protest movements, behaviour like this isn’t shamed: XR makes a conscious effort to accept and acknowledge everyone’s contribution.

This is due in part to the kinds of ties the group cultivates between its members – a direct product of Hallam’s research into protest design. XR has little to no brand management team and is highly decentralized. Anyone can do anything, so long as they check with the people closest to them in the extended network of loosely connected XR chapters. XR’s strength lies in the capacity to create meaningful bonds without restricting forms of action. In this way, Jenny, who is spending her Saturday afternoon sat in the small camp illegally blocking a junction at Parliament Square, worked with XR’s Norwich chapter to have a say in some key structural changes in the messaging the group uses.

For Jenny, the way the XR group works together is an expression of the way she sees the world. She feels connected to the earth: we are a product of it and thus part of it. “When people talk about doing harm to the environment, I think: ‘What?’ I don’t see a border there. We are the Earth.” Finding a group that was bound together but still open to individual expression of its core principles felt like a homecoming to her. She is not angry either, but there is a deep sadness when she thinks of the way other people have responded to the crisis.

XR Norwich have taken as their symbol a murmuration of starlings: moving independently but still working in unison. Watching people holding the XR logo whilst blocking a highway in Denver, Colorado, or ‘dropping dead’ in the middle of the street in Palma, Mallorca, it’s easy to be struck by how appropriate the decision was. Like starlings, the ties that bind XR together are strong enough to maintain a whole, yet still flexible enough to allow each member to express their unique connection to the central issue the group wants to tackle.

One of the lesser-publicised problems with climate breakdown is that the climate is a ‘non-linear system.’ Hallam is very clear about this: “Make no mistake… once we hit those thresholds, we are fucked.” As a non-linear system, changes can appear to be happening gradually. A steady climb in CO2 parts per million or a gradual melting of the ice caps are undetectable. However, once a specific critical mass is reached, the new levels of certain materials in the atmosphere will cause chain reactions across the interconnected climate system that establish a new equilibrium which is difficult to reverse. By this point, it won’t be enough simply to return the atmosphere to its previous composition. We will be in a new state of balance – one that is not in our favour.

This rational, systemic way of thinking is rarely associated with XR’s approach to activism and protest design, and yet it has shaped much of the group’s ground strategy. Hallam is fascinated by psychology. He refers to Robert Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion as the seminal text in inspiring his own work. The research and the work Hallam has done with the other core members of the movement have shown that after around a thousand arrests, and with the support of a meagre 3.5% of the population, the system as it stands will break and reform.

In a sense, this is the technocrat’s protest movement. In a video explaining the methodology of the group, Hallam describes why nonviolent direct illegal action is the most effective method of creating change. The pitch is carefully argued and highly convincing and as the example of the April protests demonstrate, the group is able to pull together a massive variety of people under its umbrella.

This design has also exposed the particular weaknesses of XR. Decentralisation limits the opportunity for a charismatic figurehead to come forward; Greta Thunberg, though not specifically associated with XR, is an exception. XR’s extended sit-in protest style also limits the possibility for certain sections of society to participate: there’s no escaping the fact that for most people, taking two weeks off work to sit in the middle of a road in central London just isn’t feasible. There’s also no dodging the fact that even in central London, participation by ethnic minorities remains slim – in itself a symptom of a very ‘white’ British climate activism scene which XR members are attempting to remedy with calls for greater intersectionality.

Confronted with the imminent collapse of our life support systems, the greatest risk of failure facing XR, for Monbiot, lies in the question of narrative. What story is XR telling people? Is it a story that resonates with them and does it chart an obvious path to recovery? “Almost all successful political and religious transformations have been accompanied not just by a powerful narrative, but by a narrative that has a particular structure.”

This is the so-called ‘Reformation Story,’ a narrative which you can trace in everything from the Bible to Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings. It is a simple, age-old story. Disorder afflicts the land, caused by powerful and nefarious forces working against the interests of humanity. But the hero confronts these powerful forces against all odds to overthrow them, restoring order to the land.

Many of the parts which make up XR’s own ‘Reformation Story’ are already in place. The disorder is obvious: 97% of scientists agree on the imminence of mass extinction. The powerful and destructive forces working against humanity’s interests are also obvious: unfettered consumerism and oligarchic power (those behind the 100 companies creating 71% of global emissions). Who the heroes are is clear: XR. The people. You. But how does the story end? What does restoring order look like?

This is the faultline that keeps Monbiot awake at night; the chink in the armor; the loose end that threatens to unravel the bonds that hold XR together. What does succeeding look like? What exactly do the people blocking city streets imagine the authorities should do? Hallam and Monbiot both admit that the way in which this new equilibrium will be found is hard to predict. Modern society is a non-linear system, just like the climate. Bound together in innumerable ways, it is nearly impossible to predict how changes will propagate through our complex and interconnected system.

XR have tried to confront this problem head-on. One solution is obvious. To help manage the transition to a new normal, XR want to set up ‘Citizens’ Assemblies’ to oversee the changes the government is too slow to do themselves (or too in denial and dictated by vested interests to address). Oxford City Council recently set up the first of these climate focussed ‘Assemblies’ and others are following suit.

A somewhat loftier solution is Monbiot’s concept of ‘private sufficiency/public luxury,’ which he has been honing with his friend, the prolific economist Kate Raworth. Instead of a system which tries to ensure that everyone achieves ‘private luxury,’ we create one which guarantees everyone sufficiency, with luxury in the public domain. The pursuit of public luxury creates more space for everyone. “The same applies to ecology,” he says. “If we share instead of hoarding our resources we can distribute the wealth and use much less of it.” As Raworth explains it in her Doughnut Economics blueprint, it all sounds very simple. And yet, it is a foray into a radically alternative kind of economics, one explicitly honed to the Anthropocene, or, in other words, the current ecological age in which humans are the dominant influence on the environment.

It is impossible to know how the story ends. For the time being, it seems to be enough for XR to serve as a space for people to express the connections they already have; whether with nature, with their grandchildren, or otherwise. At the same time, XR make it possible to create new connections with others who are undertaking all kinds of direct action in the face of climate breakdown. As a cultural moment, XR binds together even those who sit on its periphery. Take the Davidsons, who are practising their very own kind of ‘Doughnut Economics’ in the form of ham sandwiches, which they eagerly devour underneath Marble Arch. They’re on a weekend away from Glasgow and have wandered into the protests by accident. All of them, from the ages of four to forty, share a feeling of relief. At last, it seems, someone is doing something. They see XR as part of a great wave of change in environmentalism, particularly in how people think and talk about climate breakdown. They see Hallam’s anger and Monbiot’s determination – they see the watershed moment which XR and other movements constitute; the epiphany; the very instance, collectively, when people began to stop looking away. In this sense, the Davidsons’ connection to XR is just the tip of the iceberg. What about us, the authors of the words you’re reading right now? What about you?

It remains to be seen how XR’s protests will affect the way things are, both now and in the future. But one thing is for certain. Every person looking away whose face XR grabs and turns towards the spectre of mass extinction is a victory. Or, as Jenny might put it, with the arrival of each new starling, what was once a murmuration may well become a chattering. We can draw some hope from that.

Words by anon and Jacob Harrison (@Jacob_h_1994). Photography by Miles Aho, Anthony Mo and Jacob Harrison.