Zaha Hadid: “Life is not made in a grid.”

by George Grylls | July 21, 2015

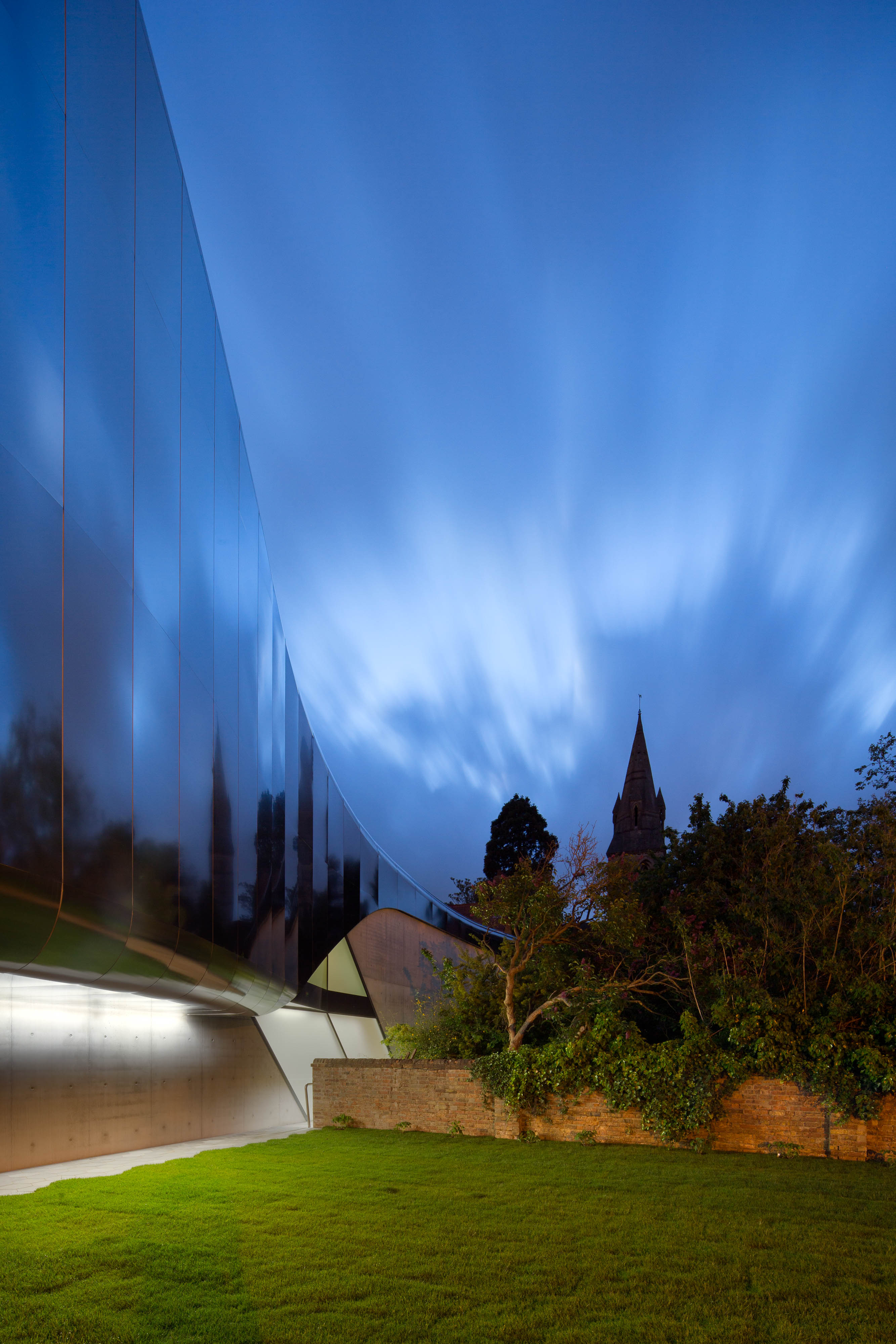

Dame Zaha Hadid is one of the most famous architects currently practising in the world. She was the first female recipient of the Pritzker Prize, which is commonly referred to as the ‘Nobel prize of architecture.’ Her Middle East Centre is due to open at St. Antony’s College on Tuesday 26th May. The building has been coined the ‘Softbridge’ because it straddles two existing buildings like ‘a bridge between the Eastern and Western worlds.’

Is the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s a particularly personal project given your Iraqi heritage? Is there still room for personality in a firm that employs around 400 people?

I must say that all the projects interest me equally. There is a personal connection with this project on several levels. My brother was a fellow of the college and as a centre of Middle East studies, there is an obvious connection with my own history. I am an Arab, but I was not brought up in a traditional Arab way, I have not lived there for many years, so in that sense, maybe I’m not a typical Arab. I’m Iraqi; I live in London; I don’t really have a particular place.

Looking back to when I was growing up in Iraq in the 1960’s, there was an unbroken belief in progress and a great sense of optimism. Iraq was a new republic. These ideas of change, liberation and freedom were critical to my own development. It was an incredible time of social reform and nation-building. This ideology has been very important to me.

Architecture is certainly not a solo act. I have a wonderful team in the office that I’ve worked with for many years. The office has a great atmosphere of incredible energy and many people have contributed to the work.

It’s a different kind of operational psychology today. Previously, in an architect’s office, each individual would do almost everything: make a model, design, answer the phone or make a slide presentation. Now you have people who specialize in different aspects of the design and construction process, so we’ve established a collective research culture where many talents can feed off each other’s ideas and experience.

From Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor to Phillip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, Oxford has incredibly strong architectural pedigree. Were you conscious of this history when designing the Softbridge?

We were very aware of the quality and depth of buildings in Oxford. There is a real depth of commissioning, not only centuries ago, but also in recent history. Arne Jacobsen at St Catherine’s College is an obvious example. We also discovered Oscar Niemeyer’s proposal for student housing at St Antony’s. It was never built, but his design explored some interesting ideas. A good understanding of space and materials is crucial when we strive to achieve that same level of quality as the architects who came before us.

The Softbridge rises, very elegantly in my opinion, to reflect and respond to the Grade II listed Hilda Besse Building by Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis opposite. Do you appreciate this Brutalist building and the movement to which it belongs more generally?

There is an integrity within the Brutalist work that displays a real commitment to ideas of change and liberation. The 1960s were an incredible moment of social reform and levelling. The beauty of these projects is in their material and austerity. There are no embellishments to make them conform to the status quo. Brutalist architecture fell out of favour and much of it has suffered neglect or has been demolished – but it includes some very good buildings that are beginning to be understood and appreciated again. These projects appear to be of their time, and yet they are essentially timeless, continuing a narrative of social reform and expressive materiality.

Can you explain your decision to use such a distinctive stainless steel for the Softbridge. What effect do you hope it will give?

After a long process of evaluation and consultation we decided on a stainless steel cladding. We built several large facade panel samples in different materials and colours. Each of these samples was left exposed to the elements over the course of several months. We then evaluated the results with the client and the planners and the stainless steel façade proved to be most resilient whilst being easy to maintain. Its surface reflects light very softly to give the building a wonderful ephemeral quality, introducing a contemporary element amongst the historical sandstone buildings. The contrast works to highlight the integrity of the past and the present. We and the client both felt that Oxford needs to continue to look to the future as much as it protects its heritage. The stainless steel reflects the existing protected buildings and trees and the endlessly varied weather conditions, but it is also a physical entity, a representation of the present and ever-changing evolution of both Oxford and the wider world beyond the city.

From the Heydar Aliyev centre in Baku to the Olympic Aquatics centre in London, all your buildings, including the Softbridge, emphasise curvature and you have professed an aversion to rectangularity. Is this an important battle in the history of architecture? Do you ever think of your buildings in the context of movements?

Architecture follows neither fashion nor political and economic cycles – it follows the cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Contemporary society is not standing still, and buildings must evolve with new patterns of life to meet the new needs of its users. I believe what is new in our generation are the much greater levels of social complexity and connectivity. I think contemporary architecture must move beyond the 20th Century architecture of orthogonal blocks, repetition and compartmentalization – towards an architecture the 21st Century that addresses the complexities and dynamism of our lives today.

Consequently, my work is operating with concepts, logic and methods that examine and organize contemporary life patterns. The repetition and separation that defined buildings of the last century has been superseded by buildings that engage and integrate.

My ambition has always been to create fluid space. We like to work with fluidity because we believe it visually simplifies everything, and you can then cope with more complexity in a building without crowding or cluttering the visual scene. People do ask ‘why are there no straight lines, why no 90 degrees in your work?’ This is because life is not made in a grid. If you think of a natural landscape, it’s not even and regular – but people go to these places and think they are very relaxing. I think that one can do that in architecture. We often look at nature when we create built environments; at her coherence and logic.

Ultimately architecture is all about well-being; the creation of pleasant and stimulating settings for all aspects of life. But I think it is also important to build projects that give uplifting experiences that inspire, excite and enthuse. Part of architecture’s job is to make people feel good in space.

Architecture is a notoriously male-dominated profession and you are often asked about the role of women within it. Would you prefer that your buildings spoke for themselves or is it a necessary distraction to your work?

People used to think women were not logical thinkers. Well that is absolute nonsense. It was also assumed that a woman architect could not take on a big commercial project – and I do recognise a bias that pushes women towards designing interiors. It is thought they understand interior shapes- and I’m sure they do understand them better than men actually- but the idea is based on the presumption they will prefer to deal with a single client rather than with corporations and developers. I am sure that as a woman I can do a very good skyscraper. I don’t think it is only for men.

I don’t believe that much remains of the stereotype that architecture should be a male rather than a female career. 50% of first year architectural students are women, so women certainly don’t perceive it as a career alien to their gender. In our office we have no stereotypical categories that relate to gender at all.

You now see more established, respected female architects all the time. That doesn’t mean it’s easy. Sometimes the difficulties are incomprehensible. But in the last fifteen years there’s been tremendous change, and now it’s seen as normal to have women in this profession. I still experience some resistance, and I think, on one hand, it’s made me much tougher and more precise – and maybe this is reflected in my architecture.

I never thought of myself as a role model. In the beginning of my career, I always thought I didn’t want to be known as a ‘woman architect’ or an ‘Arab architect’. But later, I realized that it is critical I acknowledge the fact that I could influence others. So I think it’s important that I can – in some very modest way – help others to have the courage and determination to achieve their ambitions.

In the past you have published a book on Suprematism and are one of the trustees of the Melnikov house museum; you often cite the Russian avant-garde as a major influence. Has abstract art in the hundred years since their heyday been able to match or surpass their eye for composition?

Anish Kapoor and Richard Serra are exploring fascinating ideas of space and material. I also remember I had a great experience and discovery when I went to the Reichstag wrapping by Christo in Berlin. There were millions of people there singing and dancing; they all flocked to see this building being wrapped, because it was a strange idea. That’s when it became clear to me that people are very interested in fantastic projects – those projects that make fantasy become reality. It was an extraordinary event, and very important historically, because it debunked the idea that people only liked the familiar. In Berlin people were not only fascinated by the idea of wrapping an object, but how it was wrapped and how you make something new and unexpected out of something very familiar.

Finally, you are a self-professed workaholic and have an incredibly punishing schedule. Has travelling the world become a chore yet?

It’s very difficult to get anywhere in any profession without being meticulous. I believe in hard work, but it’s also important to learn how to trust others. A brilliant design will always benefit from the input of others. I never tire of visiting new places; of learning what’s around the next corner. It’s always exciting to experience something new.