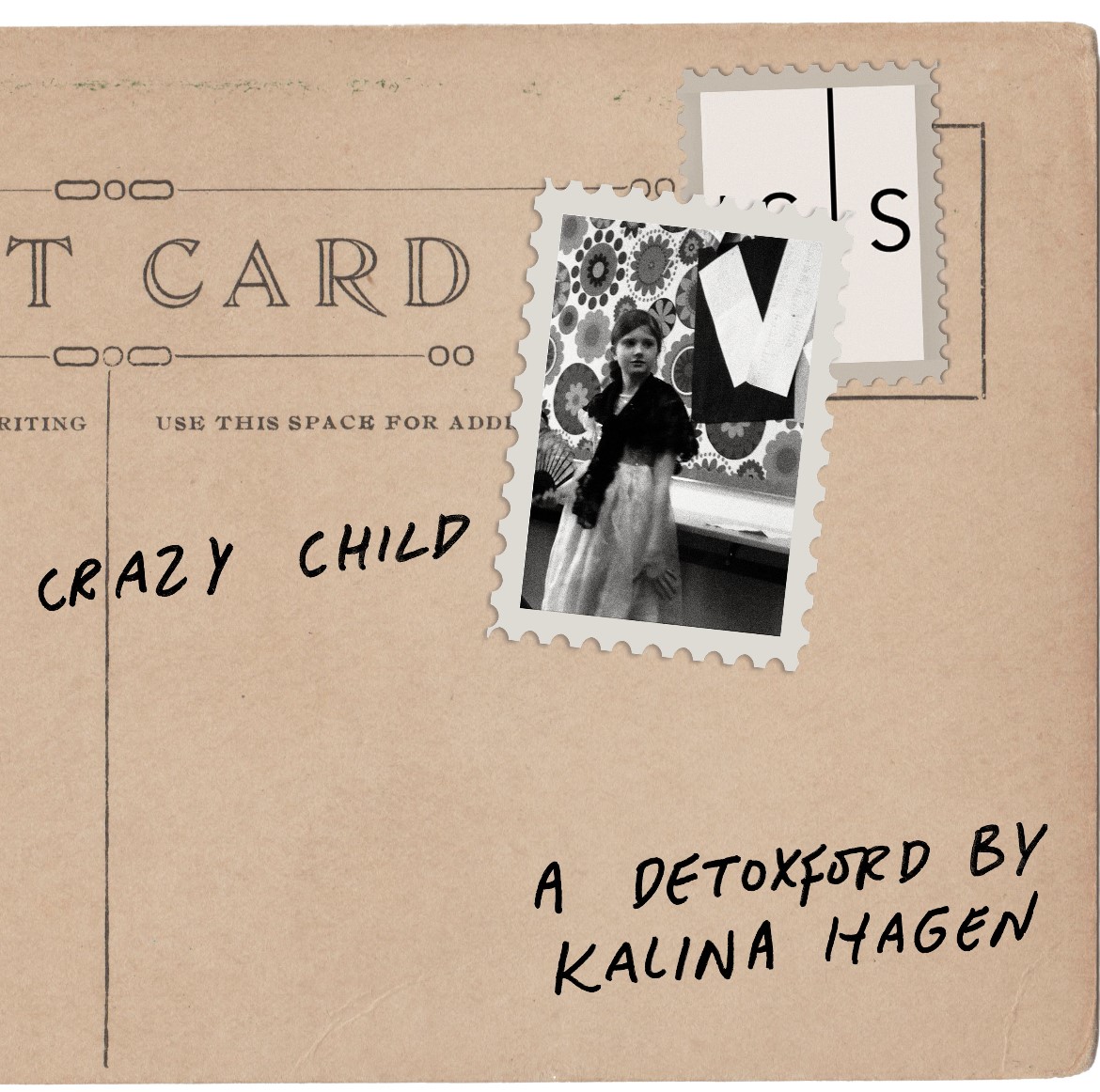

Slow down, you crazy child

by Kalina Hagen | August 13, 2024

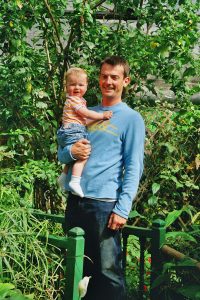

The first time I arrived in Vienna, I was eight, ginger, and unimpressed. It was March, and I’d just been uprooted for the first (but certainly not the last) time. My father’s previous employment had meant that I’d spent the first eight years of my life in one house in Brussels. It never really felt like home in a complete sense. My mother is Australian (although, as I’ve been repeatedly informed by the Aussies I’ve met at university, ‘Australian’ is a very strong word to describe a woman who’s lived down under for a grand total of nine months of her life). My father is Norwegian, and you can tell (he’s 6’2”, making him one of the shorter men in our family). So, when I was born in Brussels, everyone knew that I would never grow up to be Belgian.

When my parents announced we’d be leaving the only city I’d ever known, it didn’t come as a surprise. In fact, ‘announce’ is a strong word. They mentioned it, casually, over dinner, in between news about my grandfather’s hip replacement and a debate over where we’d spend our Easter holiday that year. This isn’t a big deal, then, I thought. When the school counselor pulled me out of class one day to ask how I felt about ‘moving away from home’, and to tell me that ‘it’s normal to feel nervous or upset’, I dismissed her. ‘Brussels isn’t my home,’ I shrugged. ‘I don’t care if we leave.’

The moment I stepped off the plane, it quickly transpired that I did care. I’d always known Brussels was a temporary arrangement, but it didn’t stop me from missing the only house I’d ever known, and the garden I’d played in all my life. Suddenly, I had to get used to being unable to communicate with the world around me. Until then, my young, malleable brain had meant I’d always been the only person in our trilingual household who could seamlessly switch between all of the languages I needed in my daily life. Now, I was a foreigner, and everyone knew it. Even though I took to German quickly, it would never be as seamless and accentless as my French.

But it wasn’t the language barrier that upset me the most. What irked me more than anything else was the Viennese lighting. Streetlamps in Vienna are, like most things in Austria, old and traditional. They hang low and emit a hazy orange glow just bright enough to avoid bumping into anything directly in front of you. Everywhere else, however, behind you, on your left, your right, across the street, shadows are left eerily unlit, presumably for the express purpose of terrifying half Norwegian, half Australian eight-year-olds to bits.

These streetlamps certainly didn’t help alleviate my already anxious disposition. I had always been a nervous rule-follower, but faced with so much unsettling novelty, my feelings began to morph into something more sinister. I felt like there were terrifying monsters lurking on every poorly lit street. At first, these creatures only hunted me at night, keeping to the many shadows left unlit by Vienna’s streetlamps. With time, though, they grew bolder. Soon, my own home felt unsafe. I could barely be left alone in a room without being secretly paralysed with fear. I didn’t tell anyone about the monsters that lived in the shadows. I was old enough to know that the mythical creatures of my story books were just that: mythical. What I knew, my mind seemingly refused to believe. I, logically, concluded that I was slowly going mad. It never occurred to me that the school counselor may have had a point. Moving countries was a big deal, even if no one around me acted like it was.

My father was transferred again when I was 11, this time to Paris. I left Vienna happily, ready for brighter streetlamps and a language I spoke fluently. Conveniently, leaving Vienna would stop my ongoing descent into madness, too. After doing lots of unassisted thinking, I was pretty sure that Vienna’s suboptimal pedestrian lighting had played a pivotal role in my rapid deterioration.

So, imagine my surprise had I known that I’d willingly return one day, 18, still pretty ginger, and alone.

I’d have been pleased, though, if you’d told eight-year-old me that I was returning to Vienna as an Oxford law student. That impressive title was apparently enough to grant me a summer internship at my mother’s friend’s Viennese law firm (excuse the nepotism). There I was, back in the city I’d once ached to leave. This time, though, I was the picture of what my eight-year-old self would have considered wild success: one third of the way through a fancy degree, owner of excellent white cowboy boots, and, above all, free from the monsters that once lurked around every corner.

Years on, I consider myself a pretty remarkable mental health success story. At the ripe old age of 18, I’d say I’m a poster child for the benefits of talk therapy and Zoloft. It was obvious to me now where my overactive imagination had gotten those monsters from. I had been uprooted from the only home I’d ever known, an obviously anxiety inducing experience. I just didn’t have the language to express what was going on. However, shockingly, my anxiety didn’t turn out to be the Vienna-induced phenomenon I’d hoped. It followed me to Paris, and then when we moved again, this time to Oslo. At 14, helped along by pandemic-era isolation, I reached a breaking point. Most 14-year-olds don’t know who they are, but I did. I was anxious. No longer a Norwegian, an Australian, a multicultural polyglot, or a writer, dancer or singer: anxiety trumped them all. Anxiety became my most important identifier. I was fairly certain I’d one day lose the battle against myself, and that would be the end of it.

On my return, a decade later, 18 years old and an adult in all ways that felt important, I knew better. Thanks to 10 years of on and off therapy, I could now approach my anxiety with empathy and understanding. It didn’t define me. Really, it was a natural response to the fact that moving countries every four years during the most formative years of your life is really hard. At eight, I didn’t know how to cope with the upheaval moving caused, so my brain helpfully translated my worries into something a child could comprehend: monsters and murderers.

As it turned out, the fact that I’d forgotten most of my German and lacked any Austrian legal training made me a relatively useless intern. Besides, it was summertime. ‘There’s not actually much for you to do,’ my boss admitted a couple of days in. Mostly, I found myself not doing anything much at all for eight hours a day, yet still returning to my accommodation utterly exhausted and increasingly angsty. Paranoid thoughts began to creep back into my head. Maybe Vienna was the problem after all. Maybe Vienna and I just didn’t suit each other.

One evening, having spent another restless day at my desk, I laced up my running shoes and headed out the door in an attempt to run away from the unsettlingly familiar feelings I’d been having. As I pounded the pavement, I could hardly believe my eyes.

There they were, all around me. Thin, rectangular bulbs, haphazardly suspended between buildings on long, dodgy-looking wires. They emitted the same hazy glow that had haunted my prepubescent imagination. I felt the back of my neck shiver and my jaw tighten in a way they hadn’t in years. A voice in the back of my mind piped up, urging me to watch out for the many ax-murderers that were surely lurking everywhere in the world’s sixth safest city.

I kept running, weaving through the streets of my old neighbourhood. I was determined to resist the urge to run back to my apartment, cry, call my mum, and book a one-way ticket out of Austria. Above all, I was confused and ashamed. This wasn’t me anymore. I thought I’d been fixed. Maybe I wasn’t the poster child for modern psychiatric medicine I thought I was. Was my success story, the well-adjusted mental health I was so proud of, really so futile? All it took was returning to the place my anxiety had first emerged for me to fall apart. For days, I felt like I was eight years old again. What if I’d been right all along, and there really was something innately and incurably wrong with me?

Slowly, though, I remembered that I wasn’t eight years old anymore. I knew better than to automatically believe the voice in the back of my mind. I kept going for runs, kept facing Vienna’s dimly lit streets. There is something deeply humbling and raw about running. The human body is built to run fast and long, after all, we were endurance hunters, back in the day. When you run, you’re reminded of the human mind’s unique capability to trick the body into doing what it wants. When every muscle burns with exhaustion, the mind is where the body finds its deepest reservoirs of physical strength. The same goes for anxiety. When the mind needs help, when it feels like no one is listening, it enlists the body to make someone listen. I couldn’t continue to ignore my anxious mind, to dismiss it and suffocate it with endless activities. It was still there, beneath it all, no matter how many sports, societies, and questionable Oxford club nights I tried to bury it under. It was only now, back where it all started, deprived of those external anesthetics, that I was being forced to reckon with myself.

I left Vienna and its streetlamps for the second time with a lot of tearful diary entries, worn-out running shoes, and a decision to go back to therapy. I know better now than I did at eight. I’m not crazy. I’m anxious. But just as moving to Vienna taught me about my anxiety all those years ago, it taught me something more valuable the second time around. I don’t know everything at 18, but I know that anxiety isn’t something I can tick off on a list. I can’t neatly file it away under ‘past problems.’ It requires constant work. This time, I didn’t leave Vienna wanting to forget what I’d learned. I left hoping I’d be humble enough to remember it. ∎

Words by Kalina Hagen. Image courtesy of Alice Robey Cave.