Vogel’s Toast

by Sunny Parke | June 22, 2020

Although I was born in Scotland, my memories begin in New Zealand. Looking back at my childhood, it’s akin to a Supercut of a coming of age movie: wharf-jumping, peering into dormant volcanoes, swimming with seals around the islands, mum picking me up early from school because there was a tornado in the next street. A childhood spent salt-haired and cherry-stained under an eternal sun. It didn’t matter that I didn’t have NZ citizenship or blood or birth-right, I was a Kiwi like every other kid on my street, eating the same Weet-Bix in the morning and taking the same bus to school. In fact, the idea of nationality didn’t really cross my mind at all until I returned to Scotland for high school.

I definitely felt like a Kiwi when I first moved back. It was an alien place, Glasgow: a grey expanse of high-rise flats, dark before I left for school and dark by the time I came home, with an accent so unintelligible and slang-heavy that I could barely understand anyone for the first few weeks. I had left mid-summer in New Zealand and gone back in time, literally by thirteen hours, yet somehow by ten years as well, as I was stopped on the street by people who remembered me but who I didn’t remember. ‘Culture shock’ doesn’t even begin to cover it. Scared shitless, more like. As the years passed, of course, what was unfamiliar at first became familiar, and then comfortable. And as I drank in Scottish pubs and graduated Scottish high school and voted in Scottish elections, Glasgow eventually became home. But this reclamation of my Scottish identity came at the expense of something else. Undocumented in the eyes of the law and neglected after six years away, my New Zealand identity began to fade.

Aware of its fading, I became obsessed with hanging onto it. An authentic identity that I had once held slowly mutated into a cultural kink, a quirk for parties, something that my younger teenage self in particular used as a means of self-exoticization. I viewed myself voyeuristically through Scottish eyes – an ironic, if bitter, indication that I had already lost my Kiwi identity. Self-awareness brought no comfort. Instead, I became desperate to return, to see if I still retained any rights to my former nationality at all. Finally, on the 15th of March, 2020, I returned to New Zealand.

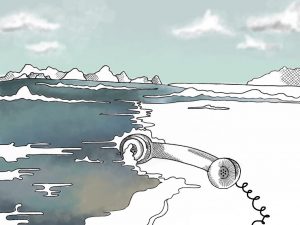

Needless to say, this exploration of identity was somewhat complicated by the emergence of COVID-19. My family and I were quarantined to our Airbnb upon arrival in the country, and it was forbidden for resident Kiwis to enter. My brothers came to visit us, but they weren’t allowed to touch us, instead sending their love across the legally-mandated two metre distance. We had dinner together – they stayed outside, us inside, talking through a window and communicating across a border. It felt unnervingly apt for my situation, to be operating in this space of limbo – neither quite in or out of New Zealand. Yet, it all felt worth it to me, because for every awkward dinner and every lap around the empty apartment, I came a fraction closer to being reunited with the New Zealand from my childhood. Unfortunately, these ‘unprecedented times’ really are unprecedented. Three days before our release from quarantine, the New Zealand government announced an Emergency Level 4 lockdown. Within twenty-four hours, borders shut, repatriation flights skyrocketed to $11,000 each, and every household in New Zealand locked its doors. Even the bridge linking the two halves of the city was closed.

Needless to say, this exploration of identity was somewhat complicated by the emergence of COVID-19. My family and I were quarantined to our Airbnb upon arrival in the country, and it was forbidden for resident Kiwis to enter. My brothers came to visit us, but they weren’t allowed to touch us, instead sending their love across the legally-mandated two metre distance. We had dinner together – they stayed outside, us inside, talking through a window and communicating across a border. It felt unnervingly apt for my situation, to be operating in this space of limbo – neither quite in or out of New Zealand. Yet, it all felt worth it to me, because for every awkward dinner and every lap around the empty apartment, I came a fraction closer to being reunited with the New Zealand from my childhood. Unfortunately, these ‘unprecedented times’ really are unprecedented. Three days before our release from quarantine, the New Zealand government announced an Emergency Level 4 lockdown. Within twenty-four hours, borders shut, repatriation flights skyrocketed to $11,000 each, and every household in New Zealand locked its doors. Even the bridge linking the two halves of the city was closed.

The only thing left to do was to re-explore the city. These expeditions were unnerving – although I could still remember my way around, the atmosphere was alien. The streets were barren, save for those out buying their apocalypse shop, blue-gloved and bandannaed like cowboys, a far cry from the no worries mentality that I remembered. A homeless man slept in the middle of a carless street like a huge cat warming itself in the sun. Someone fucked on meth raced down the middle of the road on a BMX. It was like a scene from Mad Max. Even the red-light district, normally heaving with lusty punters, day and night, was silent. The sign outside the lap-dance club advertising ‘Australasia’s Premier Striptease Club’ was missing the ‘M’ from Premier. Auckland looked more like an abandoned town from a bygone era than a city that was alive just the day before. This is not the New Zealand that I remembered. Or is it?

Doubtless, childhood memories always have a degree of false lustre, causing me to remember the whole country as little more than a tiny kingdom awash with the washing – somewhere untouched by the real world. But there is room for reason – a country in pandemic is by no means a good representation of its actuality. I know this for a fact because the pubs are shut in Scotland, and anyone who’s ever heard a single cliché about Glasgow will know for damn sure that’s not any reflection of the local culture. And so, if I look past the strangeness on the streets, affirmations of my New Zealand identity come to light. For example, our Residency Permit protects us throughout the ordeal and we are treated as citizens by the state. This allows my dad to re-enrol as a doctor in Auckland Hospital, to both assist during the pandemic and to provide income for our indefinite stay here. In doing so, our family stitches itself back into the economic fabric of the country. There is even a strange comfort in the Emergency Alert mass text heralding the beginning of the lockdown: ‘Let’s all do our bit to unite against COVID-19. Kia kaha’, it says, [Stay Strong, it means, a phrase so familiar that it prevails despite my fading Māori]. But it’s the phrase ‘Let’s all do our bit’ that stands out to me. There’s something in its inclusivity that suggests that we’re in this with the Kiwis now. Maybe I’m wrong, perhaps it’s little more than an immigrant’s pipe dream to believe that doing your bit is enough to stake your claim on nationality. But then who knows the parameters of nationality more than an immigrant? No-one else has spent so long wrestling with its definition.

Perhaps that’s how I would define nationality in its official capacity then: caring about the country, doing your bit, and all the other buzz-phrases that you would read on a government pamphlet. But nationality as a sense of belonging, that’s different. That’s about enjoying the slow life that the country has to offer. When you are cut off from your community, will you still love the way that the Auckland sun feels? When you cannot perform your daily routine that you were convinced constructed your Kiwi identity, will you still be pleased to find feijoas on your daily walk, ones that somehow always taste better when they’re nicked off the neighbour’s tree? When the world as we know it seems to grind to a halt, will you still find a little comfort in a piece of hot, buttered Vogel’s toast? Yes, a hundred times over. We relax into the unhurried life of the lockdown, as do others around us. A neighbour laughs next door. Kia Ora, someone says to me on the street, at a respectful distance. Kia Ora, I respond. People start sitting on their porch to eat their lunch and watch life go by. Maybe I’ll do the same.

I hope that no-one thinks that I am renouncing my Scottish identity by solidifying my New Zealand identity. When I saw videos of everyone hanging out their tenement windows and clapping for the NHS, it made my heart fit to burst. I know for certain that I own that identity in its fullness; culture, as well as blood, water, citizenship and the rest. But I am not choosing whether I am more one or the other anymore. The struggle is over. I have lost nothing. I am standing under the sun and its warmth is hitting my face. ∎

Words and pictures by S. Parke