England had no Empire.

I went to the Ming Tombs on a scorching summer’s day.

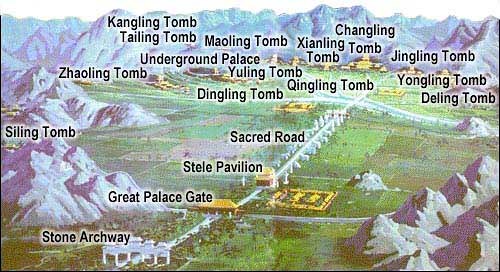

On the outskirts of Beijing, between the mountains of White Tiger and Red Phoenix, lay buried the 13 Emperors of the Ming Dynasty. Tomb is too humble a name, really. They are cities for the afterlife, complete with gates, walls with battlements, towers, mounds, and palaces in the underground.

It was the off-season. I went with my father and brother. The moment we arrived we were approached by a village woman who offered us a guided tour. She was one of the descendants of the tomb guardians, whose offspring, over the past four centuries, have formed 13 villages around the 13 tombs, between whom they married so as to avoid incest.

‘Not all men buried here deserve this honour,’ said the woman now in our passenger seat. She pointed to one of the towers in the distance. ‘Emperor Tianqi. Took his childhood wet nurse as concubine.’

The more Oedipal, cuckold, autistic emperors, who had given themselves to carpentry or immortality, through consuming the menstrual blood of ladies-in-waiting, have significantly smaller tombs than those of their forefathers. Not all emperors of Ming were buried here either. The founder of the dynasty, Emperor Hongwu, born in 1328 to three generations of beggars, who died in 1398 with 26 sons and 48 concubines, is buried in the old capital, Nanjing, occupying half a mountain. The other half buried Sun Yat-Sen, died 1925, the first president of the Republic of China.

In 1966, during the heat of the Cultural Revolution, the corpses of Emperor Wanli and his two empresses were dragged out by the Red Guards. A trial of the corpses was held, precisely 346 years after the Emperor’s death. They were denounced as the leaders of the big landlord class, and the verdict saw them burned at stake. The revolutionary students threw his golden cypress wood coffin down the river. It was picked up by a peasant who took it home and made a closet.

One day, and the village woman got excited at this point in her story, the son of the peasant and two of his friends were playing some version of sardines. As the last child entered the closet, it shut tight. By dinner time, three corpses were discovered within.

‘It was in the papers!’ We had no way of fact-checking. Scientific inquiry would attribute the incident to the density of good wood.

The Empire strikes back in unexpected ways. The palace of Emperor Wanli is 20 stories underground, beneath a 98 foot tall mound. As we went up we were told there were giant snakes guarding in the woods of the mound. Fortunately, it was too dry and I didn’t see any that day. We went down from the top of the mound, where the entrance was, and walked down some 200 stairs. The walls became slimy and cold. On a hot summer’s day I felt I needed a coat. There was mist in the palace. Inside the chamber, three replica coffins lay side by side.

As we exited we were told to not look back, like Orpheus, only this time we would be dragged back like Eurydice. We stepped out the way mortals do: left foot first, if you are a man. And we said, ‘I have returned’.

Not many people I know are suffocated by the coffin wood of empires—not many I know, in this country. But they don’t seem to be in the world of the living either.

Sometimes, imperiality is embedded in the landscape we live in. Shelley’s Ozymandias does not apply to the mountains around those tombs. The Great Wall was not built on flat lands. In fact, Ozymandias would only make sense if you grew up in a country of monuments—rather than a country of mountains, moving mountains—in which history is learned rather than lived. A country that does not understand that iconoclasm is just as temporal as icon-making. A country of traditions is not very traditional at all.

(What are mountains? There is an old Chinese tale about mountains. A foolish old man, whose house is obstructed by two mountains, decides to dig them away with his sons and grandsons, and sons of grandsons. Mao remarked on this tale as a testimony to the indomitable spirits of the Chinese people.)

Imperiality has nothing to do with conventional beauty. When I was 12 I saw an exhibition in the 798 District, the Chelsea of Beijing (as in Chelsea, New York), a series of galleries in a decommissioned 50’s factory complex built with aid from East Germany, with money from the German reparation to the Soviet. It was a one-woman show by one of my parents’ friends, consisting of a series of films entitled, great empires have to be painted with great colours.

She filmed the broken water pipes in Southern California, like Roman aqueducts, in black and white. She lived in Los Angeles and spoke about the fires. In my mind an Empire has always needed a desert. Ozymandias. The Gobi Desert. It needs suffering to testify to the vast scope of its power, vision—its inability to fulfill it; a scope of holes, a scope of impotence, of cuckoldry; an adulterous bloodline, a network of aqueducts which outstretches itself and is drying, parched, a testimony to human striving and failing. The imperial is beautiful because it drinks mercury thinking it is the elixir of life, like when we smelted all the woks in the Great Leap Forward before the famine, thinking we were building heaven on earth.

Those who reminisce about the Empire do not understand it.

The woman charged us a handsome amount. We drove back to the city and got lunch.

Words by Zac Yang. Map of Ming Tombs, Undated by Nathan Hughes Hamilton via Flickr.