Greetings from Texas

America, the first postcolonial nation, is made of squares. It’s among the angular continents, with fake borders, straight lines, someone else’s perfect shapes. And every postcolonial state from Kenya to Kansas must question: what is our culture? We have a name, a group of people, some lines on a map handed down from above—but what myths, aesthetics, democratic institutions, and local fast-food chains will define us?

Some flyover state could just make a disgusting new form of pizza and call it a day, but, like many things, this problem is bigger in Texas. Because I am in Dallas. People, as any headline will supply, are moving to Dallas. They are moving in massive numbers, mysterious forces dragging them into the centre of the American plains. Californians trundle their worldly treasures into trucks and mumble about tax rates. In faraway India, an advertisement reads: Move to Frisco. Which is sort of like Plano or Addison. The people of the world are converging across steppes and oceans, and now they’re all bunched up in Dallas.

This is not what it looks like on the ground. Here, it is clear: people are leaving. Along the highways that bisect any large American city, trails of new housing are in retreat. The housing is fleeing straight up the north-south interstate, straight into Oklahoma, and taking along condos and $20 hamburgers and whatever they do in AI data centres. Highways of Death on daily commutes. Suburban school districts taking on debt the size of an island nation’s GDP: the future, and here.

Texas, being unique, has—what do you know—cultural anxieties about this whole endless socioeconomic expansion thing. And many of these anxieties are reflected in—and this has never happened anywhere else before—debates about immigration. The most telling form of this is intranational immigration. Like, from California.

A common campaign slogan: ‘Don’t California my Texas’. What does this say about Texan identity? Well, the most obvious point is politics—intellectual luminary Ted Cruz is trying to Texas us into political conservatism by turning California into a verb here. But most of these Californians are conservative refugees from Comrade Newsom’s regime. In their new homeland, they embrace elaborate Homecomings and Bucees[1] with the zeal of tradcath converts. But there’s still something un-Texan about them. There’s something else in the deep, beating heart of our state that they’re missing. I think it might be Cowboys.

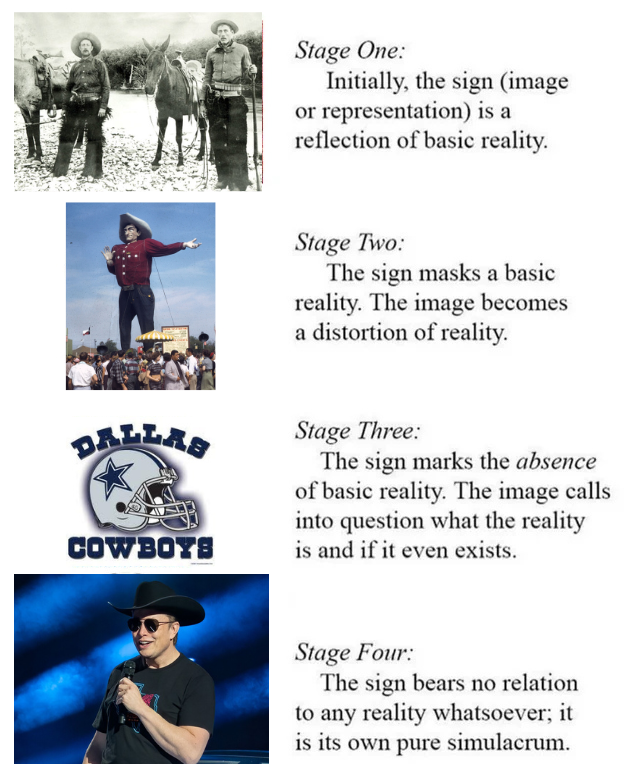

Them Cowboys are a simulacrum: a reference that doesn’t refer to an underlying reality (see my above graphic). Dallas, and the most heavily populated areas of Texas, really grew due to drilling oil, which insightful readers may find has nothing to do with cows, or even, necessarily, with boys. But the mythos of the two industries blended together. I thought about this when watching the sports documentary, America’s Team: The Gambler and his Cowboys (‘Gambler’ here refers to the risky oil business, not a casino).

Identity is an important thing. It concerns the deepest philosophical questions, like ‘who am I?’, and ‘what do I live for?’ America’s Team was sort of about how football (American) became a part of Dallas’ identity, by referring to things that never even existed there. Football is an eleven-a-side sport with rules somewhere in between rugby and the Iraq War. It also has nothing to do with cows. The documentary was about Dallas Cowboys football team, the most-highly valued sports franchise in the world, and how Dallas was once known for JFK getting shot there (bad referent) but is now known for its football team (good).

It has a lot of cowboy hats, sports footage, and That One Time When a Star Player Got Caught with A Rock of Crack Cocaine, Which Is Usually Not Ideal, But He Got an Insanely Lenient Plea Deal Because He Was Good at Football. The very legal structure of the city, our constitutional bedrock, toyed with to better suit our imagined identity. Nation-building! They did not ask George W. Bush about this incident when they interviewed him for the documentary.

Identity, of course, will shift further. The Football Cowboys are really bad now, so maybe we’ll have to transition into like, AI, or something. But those AI engineers will be wearing cowboy hats. Cowboy crap is a pastiche of a pastiche: cornball nationalism, used for oil, then football, then industrial-grade meat production, then whatever Elon Musk is doing now, but forever reused.

It is a cultural signifier: one of the little things that trick us into becoming political creatures, who can, for the time being, live peacefully together. The cowboy yee-haw thing everyone identifies with is, of course, not ‘authentic’ and qualifies as an especially flimsy simulacrum. But I don’t know what to say if you’re really searching for authenticity here. Go to California or something.

[1] A NOTE ON THE ONTOLOGY OF ‘BUCEES’: Bucees is a Walmart-sized (i.e., massive) petrol station mostly found in Texas. It quickly became the state’s cult favourite for two reasons: the bathrooms are clean, so you can take a dump on a road trip without having the typically feculent gas station bathroom experience; and, due to its size, if you got tired from sitting down in your car all day, you can eat a big greasy burger or another meat-based sandwich. But many Walmarts, or even Sam’s Clubs, have petrol stations. What makes them different from a Bucees? The astute reader would note that a Bucees is always in a remote area, giving the chain its ‘road trip’ identity. But as the Texan metropolitan areas expand upwards to Oklahoma and downwards to the plains, will the Buceess caught in this sprawl die out, hunted down by Walmarts? Will they, being of the same substance and function, now unite? These and many more questions must be answered.

Words by Myles Lowenberg. Image courtesy of Myles Lowenberg.