How to hold: Pina Bausch’s ‘Nelken’

They bloomed before you, these 8000 carnations. You are outnumbered by flowers. You do not know whether they celebrate or eulogize. How could you know, with only one line in the programme to guide you? “For love is as strong as death, and its ardour terrible like hell.” You tiptoe in. The silence is the low sound of a heart on the speakers. Everyone is shy: it is no longer an evening in town.

Yet you have come to see it, this play between the mouth and the breath, between two and four lips. You have wanted to see Pina Bausch’s work for a long time. You know she is without a doubt the greatest European choreographer of the second half of the twentieth century, that she shows bodies like no other, that, between theatre and dance, she has invented a form. Each element becomes a gesture: lashing, hair, cloth.

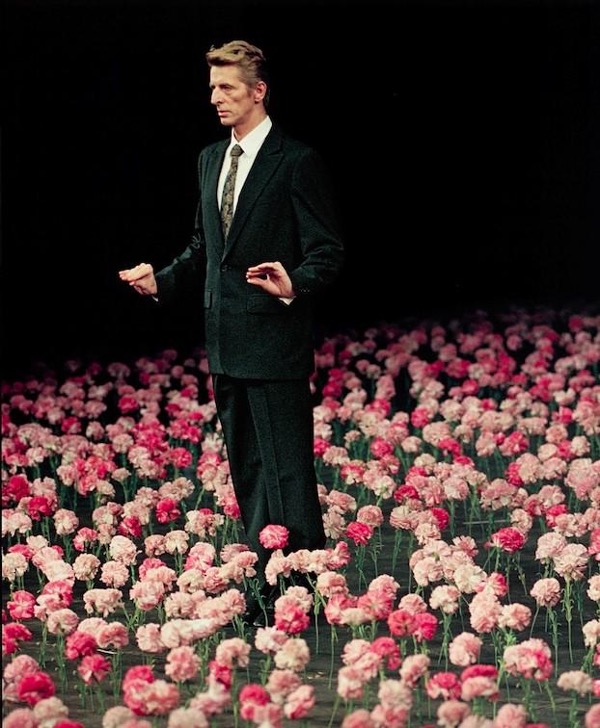

Tanzabend II, 1991

Early, the dancers prudently walk down the steps, and into the audience. Each picks a spectator and offers an arm: “Would you follow us outside, please?” They leave, and you wait. The show has begun and now it continues without you.

Nelken is a collection of sequences. 16 dancers let loose in a field of flowers multiply gestures to become a lover, a bird, a sky. A couple pours soil over their heads. A woman tickles a man until his scream is lost between pleasure and terror. Another is naked except for underwear and an accordion: she crosses the stage without a word. A man in a suit listens with you to The Man I Love. Lips sealed, standing still, he signs the lyrics: someday, he’ll come along—two fingers walking up his arm—the man I love—two fists crossed over his heart—and he’ll be big and strong, the man I love—a circle around his arm—and when he comes my way, I’ll do my best to make him stay. The song ends. He looks at you. He slowly leaves.

This is a world under watch. A game of “Red Light, Green Light” grows tyrannical: “You moved!”, the leader says. Yet the game would stop without this movement: this authority needs its subjects’ disobedience to survive. The dancers eventually force the leader to play, making him run from front to back. Laughing, they do not refuse the rules of the game: they refuse the game. As dancers hop in pink tutus, a man requires their passports. Having consulted them, he says: “You may continue to hop.”

Whether in speech or dance, the troupe asks only this constant question: why are you here?

No answer would suffice: as the dancers dart in and out of view, neither here nor there is safe. They are hounded: they hound you; they are loved: they love you; they are gone: you are still here, somehow. Bewildering, unjustifiable, unbearable, presence and absence are made equal: no equality but that of the unbearable.

A woman weeps like a child, takes a new voice, and scolds herself: “Now that’s enough! You’re not going to make a scene here in front of everyone, are you!” They grow defiant. One flaunts classical steps: chaînés, grand jetés—“you like that? you want more ?” In a tragic sequence, four dancers build metal structures on the stage and slowly prepare to jump. Two German shepherds enter. Menacing and mechanical, the troupe moves forward. They clap their hands from side to side under the sudden half-light.

Only one paces frantically. She screams for help, at you, at them, at technicians. But no one comes, no one gets up, not even you. As the company moves back and forth, another dancer emerges from the side of the stage and with a smile “I just wanted to say how wonderful it is that you are all here tonight.” Adjuration or adoration cannot help: the four men fall, startling the two guard dogs.

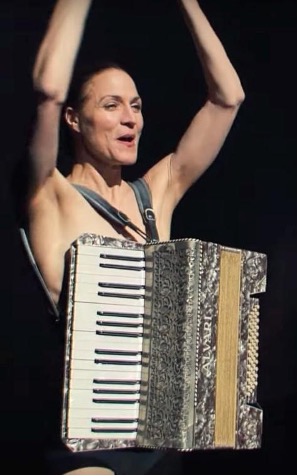

Nelken, 2024. Photograph by Oliver Look

But the height of the terror is a simple scene: a group of men approaches a woman. Menacing, they are about to hurt her. They stand around the table at which she sits. One by one, they jump onto it and let themselves fall with a crash. She walks backwards with her chair; they fall louder and louder, over and over, until she is cornered, screaming. They are so close to you as to be impossible. You shake with your row every time they fall. This is a violence worse even than a blow: here, they make you watch them hurt. They can do far worse to themselves than to you, hurt you far more in their skin than in yours.

Nelken at the Adelaide Festival. Photograph by Tony Lewis.

With each gesture images unfold: the gift of the eucharist, a fascist salute, a hand to your cheek. Bausch has a stern generosity: how to stroke a cheek without striking it? You frantically look for the answer. They spin, show off, scream, push you away, pull you close, jump, kiss, head over heels, off the top of their head, cross their fingers, let their hair down, keep you at arm’s length, get him off your chest, pull their teeth, give a hand –

There is a gentleness to this cry, a humour. Exhausted, a dancer leaves the stage, ordering another to replace him: “If you come looking for me, I’ll be in the refectory !” Immediately after, he returns with a colleague, whom he introduces in a snarl: “She’s young and fresh. She’ll continue. You’ll like it very much and so will I!” She leaves shortly after. Fuming, he stomps back: “I am told she has been indisposed!” It is this humour that lets you feel. The 3 kilos of onions chopped on stage make you cry, but when they are immediately followed by one of the play’s most emotional sequences, you have been given a shelter for your tears: of course you aren’t crying, they are only onions.

Finally they tell you to get up. They say: put your right arm forward, then your left arm half-open, then your head to the left, then close. You can barely stand: they teach you to hold. And if you ask why, they can only tell you how.

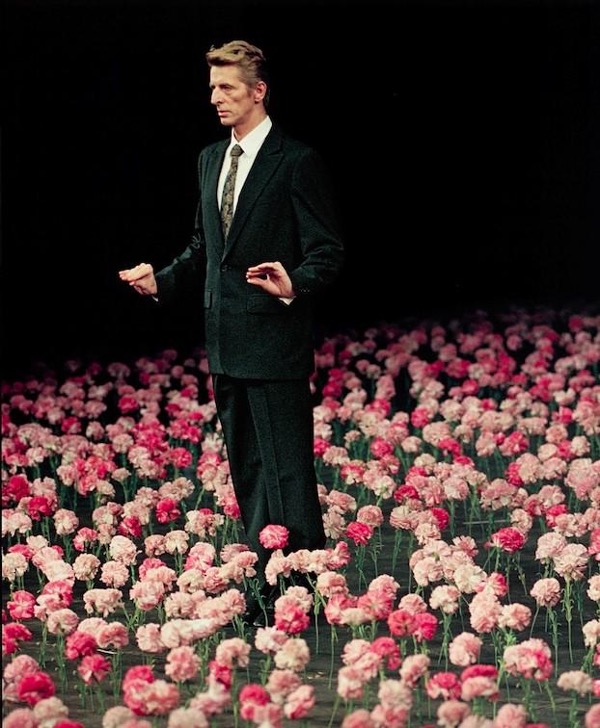

Still silent, the lady with the accordion returns.

In 4 gestures, she teaches you the seasons:

Pina, dir. Wim Wenders, 2011.

“It will soon be spring, small grass”

“Then, comes the summer, high grass, sun”

“Then, comes the autumn, the leaves fall”

“And then: winter!”

“Spring, summer, autumn, then: winter ! Spring, summer—”. You hold all the seasons in your hand: The Man I Love returns.

All dancers climb back on stage and find their chairs. Before sitting down, they answer the question “why did you become a dancer?” They are sitting, moving slightly. You too are sitting, heaving. You shiver, your heart trembles or maybe beats, your body beats or maybe trembles. They sit for the class picture, the lights dim: you take the picture, you take it with you. You hold, you behold, you stumble out: held to what you cannot hold.∎

Words by Hugo Jeudy. Images: Oliver Look, Tony Lewis, Wim Wenders.