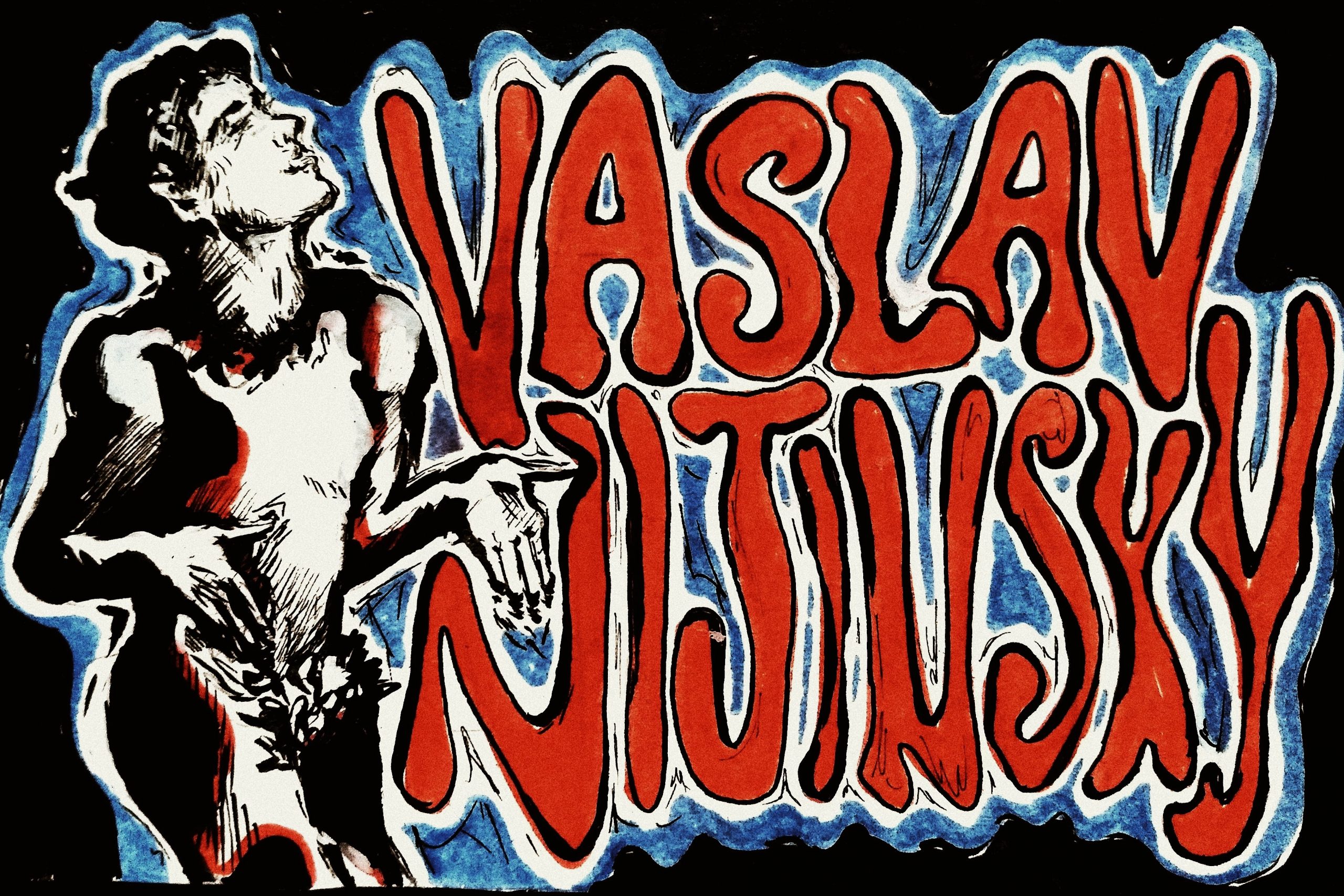

Vaslav Nijinsky

by Rita May | January 15, 2021

I often pretend to be in love with Nijinsky. It’s easier that way, I tell myself.

Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950) was a Polish-Russian ballerino and choreographer who is often credited with the modernisation of dance. His most famous piece, The Rite of Spring, was so radical in its time that the audience rioted at its premiere. Nijinsky was not only a dancing prodigy, but beautiful, beyond what words will do justice to, all doe eyes and elaborately combed hair.

He is often called the greatest male dancer of the 20th century – not merely a man but something greater than human.

Nijinsky’s final performance was in 1917, when he was only twenty-seven years old. Those who were present say that Nijinsky displayed such erratic confusion on the night of his final performance that he appeared beyond comprehension. His accompanist, they say, wept at the demise of a great artist.

Nijinsky was, by this point, in the midst of a psychiatric disorder we now know as schizophrenia. Nijinsky the man had been lost to the world, and his life became a tragedy.

There is no record that Nijinsky wept that night alongside his accompanist. In fact, the only records we have of his attitudes toward his condition are recorded in the diary he kept for six weeks between January and March 1919. This is what I hold in my hand now — all that remains of him for us to know.

Nijinsky’s diary is a rarity. It gives us insight into the mysterious process of succumbing to madness. At times it is a manifesto of love for humanity, with passages such as “everyone has a nose, eyes, etc., and therefore we are all the same. By this I mean that one must love everyone.” At others, Nijinsky is cruel and narcissistic. He criticises his wife, and says he was disgusted by a prostitute’s menstruation. He calls himself God, over and over.

The pages reflect a tension between the divine and the mortal, existent in his body.

This is a tension I know well. Up until the age of fifteen, I occasionally experienced moments when time seemed to stand still. Kaleidoscopic colours would enter my eyes and I would see the world wavering in front of me. I could barely move, and when I did, my body felt heavy and weak, as if I were walking through jelly. The physical sensations should have been frightening, and yet, in my heart, I felt a calm I have never experienced before or since. It was as though I had been imbued with a fragment of heaven. I would have happily lost myself in this state forever.

A central aspect of schizophrenia is that it defies understanding from the outside. It’s in the name itself. The word schizophrenia combines the Greek skhizein–‘to split’–and phrenos–‘of the mind’; it means, quite literally, a splitting of the mind. The patient’s mind is distorted, lost to the outside world. It is as Esmé Weijun Wang put it: to have schizophrenia is to “deteriorate in a way that is painful for others.”

I never told anyone about my strange sensory experiences growing up. Once the moments of bliss had passed, shame and fear set in. For a long time, the only terms I could find to label my condition were madness, insanity—too far outside the norm of human experience to feel like it could belong to a proper person. For a while, I was terrified that I was developing the prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia—symptoms that are sub-diagnostic, and which appear several years before the onset of the full-fledged disease.

It was not until years later that I discovered my experiences were more likely a rare form of childhood epilepsy. I have fancy words now, like temporal lobe seizure and dopaminergic to describe the probably neurological basis for my visions. But knowing these words, having scientific articles to cite about this condition—that changes nothing about how I felt, or about my longing to forego reality for those moments of bliss.

I wonder what Nijinsky made of his own schizophrenia. To me, at least, it never seems as though he is distressed by the condition itself. His diary does not express beliefs in non-existent persecution; nor does he indicate that he is hounded by any frightening hallucinations. Rather, the sentiment that appears time and time again is his distress at the reactions of the people around him. At one point he writes: “I am afraid of people because they do not feel me, but understand me.”

Nijinsky’s wife, Romola, was one such person who, whether intentionally or not, brought distress upon her husband.

Romola Nijinsky was a conniving woman who stalked Vaslav and pretended to be a dancer in order to convince him to propose. She was infatuated with Njinsky, but did little to grant him autonomy after he developed schizophrenia, taking many lengths to distort his public image after diagnosis. She extensively edited his diary to make his disjointed thoughts appear more coherent, and to conceal his sexual encounters with men as well as women.

Perhaps Romola meant well. Perhaps she made all of these changes and editions simply out of the desire to save her husband from falling into disrepute; perhaps she still wanted his legacy to be that of a divine creature who had blessed this earth

Nevertheless, Romola failed to protect Nijinsky from the thing he feared the most: hospitalisation. Nijinsky’s diary is filled with anger at Romola for consulting a doctor as he slipped further into psychosis. He writes to her, “You have trusted a stranger, and not me.” Romola no doubt wanted to help him; still, her actions pushed him away. His deterioration pained her, and her pain fueled his hatred towards her.

Nijinsky’s experience of having a stranger’s opinion prioritised over his was a fact of psychiatric treatment in the early 20th century : the desires of the patient came second to the expertise of the doctor. Thankfully, things are better nowadays. There is currently no magical treatment for schizophrenia, and it is generally considered a condition to be managed rather than cured. Eradicating hallucinations or delusions is not always the goal of treatment.

In fact, patient-focused treatments, which seek to identify individual causes of distress, have become increasingly popular. Rather than aiming to make them more manageable for others, approaches that genuinely aim to improve patients’ lives are growing more and more ubiquitous.

Yet even now, the mentally ill can be treated as subhuman far too often. It is still legal to involuntarily hospitalise and physically or chemically restrain a patient who has been deemed not to possess mental capacity, as long as it is done “in the patient’s best interests.” The issue is: who gets to decide what the patient’s best interests are?

Today, many would say it would have been in Nijinsky’s ‘best interests’ to be ‘cured’ . Such a shame, everyone says, that his career ended so soon. What could he have created if he had had five more years, ten, even, to contribute to the world of dance?

Such attitudes completely neglect the richness and humanity that Nijinsky’s diary holds, albeit hidden beneath a layer of what we call ‘madness’. The text is clear: Vaslav Nijinsky was not a violent man, nor an evil one. This was a man who wrote, “I love everyone, and I do everything for other people” and “My madness is my love towards mankind.” He mentions devotion to God repeatedly, as if the nature of his schizophrenia had brought him closer to heaven. His diary is filled not only with suffering and the fear of others, but also with the all-encompassing joy of feeling connected to the universe at large, a joy so strong that it is almost painful, begging to burst the entire soul at the seams.

When I read Nijinsky’s words, they are reminiscent of my own childhood experiences, in which I felt full of the world, too full, my eyes bursting with colour and light. Life, in those days, was experienced to the extreme. I was afraid of what these experiences would mean for me, but ultimately, I was filled with joy. I would not take any of it back, even now.

I like to think that Nijinsky’s thoughts and feelings reflect my own. I do not have people in my life who have gone through the same experiences as I have, or who know that the confines of normal life are a mere fraction of the possibilities contained within human experience.

I like to think that Nijinsky understood the loneliness that comes with these thoughts, because I do not want to face the notion that I could be alone in this feeling.

I still pretend to be in love with Nijinsky, because I would rather tell myself that I am infatuated than that I am afraid.

My fascination with him is both affectionate and morbid. On the one hand, he seems to be what society deems a ‘good’ mentally ill person: even though people do not truly approve of him, they accept him because he made a contribution to history that others can consume and enjoy. As a child, he was proof to me that I could still make something of myself even if I went ‘crazy’, proof that I could be loved in spite of what I was. I became obsessed with leaving something permanent behind before I evaporated into nothingness–obsessed with honing my writing skills so that, like Nijinsky with his diary, I could preserve a piece of myself for others to remember me by.

Having said this, Nijinsky is my worst nightmare. I still wonder if I am wrong about my retroactive self-diagnosis. I wonder if these are just my ‘good’ years, and that in time, my symptoms will come back with a vengeance to consume me. Even if I am lucky enough to create something that will make a lasting change in the world like Nijinsky did, I do not want to be remembered as a tragedy. I am sitting here with mortal flesh, soft arms and thighs and a heart that will give way someday. Like Nijinsky says, I have a nose, eyes, etc., and because of this, I am the same as you, as anyone else. The only difference is that I once felt as though I had heaven in my palms, and I still think I would trade the rest of the world for a few moments of that bliss. The sweetest wines and the softest kisses pale in comparison to what I once felt. I am ‘better’ now, which is to say, more sane. But I feel as though I have been robbed of heaven.

I want to want a normal life, but it feels not quite right, as if I am out of tune while everyone else is playing in perfect harmony. And I am afraid of how the people in my life would react if I were to admit this.

I want to live in a world where everyone understands that to be human is more than just this life where the colours are grey and emotions barely deviate from some arbitrary midpoint; I want people to feel as I once did, with feelings so strong that they do not think their bodies can contain it all. But I know that such experiences are strange, or rare, at the very least. And this makes me very lonely.

When the loneliness sets in, I like to open up Nijinsky’s diary to a random page and skim through the lines. Reading his words reminds me that there is a desire for a life and for feelings outside of how others experience them. Nijinsky said: “I want to dance because I feel and not because people are waiting for me.”

I want to dance too, Vaslav. I want to feel free.

∎

Words by Rita May. Art by Liz Tiskina.

Resources for schizophrenia:

Charities such as Mind and Mental Health UK offer helpful guides for better understanding the condition. Some first-person accounts of individuals who have experienced schizophrenia that may be of interest include: healthtalk.org’s collection of experiences with psychosis, Eleanor Longden’s Ted Talk “The voices in my head”, and The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang.

If you are experiencing mental health difficulties yourself, you may consider reaching out to one of the following: your GP, your local NHS counseling service (TalkingSpace Plus in Oxford), or mental health charities such as those mentioned above, which information services.