Resurrecting Killed Darlings: “Write, Cut, Rewrite” at the Weston Library

by Connie Higgins | March 11, 2024

Joan Didion needed a drink before she edited her writing. She admits as much to an audience packed into the New York Public Library one day in November 2011. “The drink loosens me up enough to actually mark up my work, you know”, she twangs as she gazes, unblushing, into the crowd. Dry humour is Didion’s trademark, but she insists on the sincerity of this advice as she hears laughter begin to mount amongst her listeners. “Really, I have found the drink actually helps.” It is hardly an enticing advertisement for the process of revision.

The words with which I am confronted in the single room that comprises the Weston Library’s newest exhibition are less soothing still. “Kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.” Stephen King’s arresting dictum has been printed onto orange paper, the last three words obligingly written in electric pink. They are the lone traces of colour in an otherwise achromatic room—darkly lit and suitably hushed, it is like the exhibition is telling us that we are about to be let in on literature’s best-kept secret.

‘Write, Cut, Rewrite’ is a reverent celebration of the writerly process. Curators Mark Nixon and Dirk van Hulle have, with palpable care, picked up the paper trail left by indecisive writers throughout the ages. Under their nursing hands, killed darlings have been resurrected, uncrumpled, and presented to us in an orderly line-up of glass cases. If I peer into one, I can see the moment Samuel Beckett decided how to open Not I (1972). What, at the top of the page, is a play that begins with the birth of a “tiny baby” is given the chop: Beckett neatly crosses his initial draft out in biro, before seizing a felt tip and committing more thoroughly to the act of execution. Immediately beneath this, a new play is born: it is a “tiny little thing” that now emerges onto the page and into the world. A few steps on, and I am granted access to what Alexander Pope’s ‘Essay on Criticism’ (1711) might have looked like without cuts. Beneath Pope’s tidy zigzagging lines lie lines that could, were it not for their untimely death, have been wheeled out in lecture halls across the world: “Many are spoil’d by that Pedantic Throng, / Who, with great Pains, teach Youth to reason wrong.”

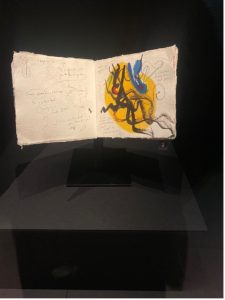

In some instances, though, the bodies are buried and gone. The notebooks of W. H. Auden and Edward Thomas rest side by side, splayed open to reveal sections from which pages have been torn. Elsewhere, pieces of paper are riddled with rectangular holes where words have fallen out of favour and been cut out with scissors. Gerard Manley Hopkins, for example, has literally excised all mention of his father from his notebook in a moment which practically begs for Freudian analysis. But acts of creation sit alongside those of deletion – George Eliot’s notebook, which she nicknamed her ‘quarry’, yields up observations she jotted down when holidaying in Spain. Of Cordoba, she writes: “I have heard of its famous mosque, which was lighted with bronze lamps made out of Christian bells.” Her hand is elegant; her prose, as ever, lucid.

It is a joy, being made privy to the “what could have been”s of these texts we know so well. The room is filled with people who have travelled across the country to marvel at Saint-John Perse’s red-inked revisions of T. S. Eliot, or Jane Austen’s discarded masterpiece. It is also filled with students who, taking a break from churning out an essay about these writers at one of the desks upstairs, have come to see their craftsmanship in action. In this room, Nixon and van Hulle translate painstaking process into pleasure; the graveyard of wastepaper they design is one that leaves its visitors morbidly gratified.∎

Write, Cut, Rewrite is on at the Weston Library until 5th January 2025.

Words and photography by Connie Higgins.