Rethinking Sustainability: How Do Working-Class Creatives Sustain Themselves in a Cost-of-Living Crisis?

by Anya Athwal | February 14, 2024

One cold October evening at the University of Oxford, girls dressed head to toe in Burberry flocked to listen to former British Vogue editor, Alexandra Shulman, discuss all things fashion. Given the recurrent questions about sustainability, I would assume that many of these garments were Depop purchases. This raises two interesting points: firstly, despite the privileged place that Oxford inhabits as an institution, people do care about sustainability; secondly, it indicates that many Oxford students can afford to.

This was something that Shulman aptly picked up on. When asked about her thoughts on sustainability she praised the merits of the practice, but acknowledged, “I think that there’s an element of classism inherent within the way that we think about sustainability. It is too easy to discourage shopping in Primark—sustainability should be thought about in terms of how many years you are planning on wearing something for”. From this, it becomes clear that one of the social challenges of sustainability is that it is often thought about in terms of a buzzword. By definition, a buzzword is a word or phrase ‘that is fashionable at a particular time or in a particular context’. It is possible that the sustainability buzzword, conceived in a fast-paced, sense, promotes more consumption than it prevents.

What does it really mean to be sustainable in fashion? To reach beyond the buzzword, I conducted a series of interviews with British creatives who are innovatively sustaining themselves, and their creative projects through the cost-of-living crisis.

The idea that not everyone can afford to be sustainable is frequently acknowledged in fashion almost to the point of being a truism. However, for these two working-class creatives, sustainability is not just a trend but an inherent way of life. It isn’t so much a conscious decision as it is a way of doing things resourcefully. And, as we shall see, the results are often unrivalled.

In 2021, the UK inflation rate began to raise exponentially. The growing crisis saw a dramatic rise in food costs and energy prices. Government intervention materialised, with the announcement of an upfront discount of £200 for all domestic electricity customers on their bills in February 2022. However, the proposed regulation came under heavy fire, with opponents pointing out that this was less of a benevolent measure than it was a ‘buy now, pay later’ loan scheme. In October 2022, inflation peaked at 11.1%, the highest point in 41 years.

It was against this backdrop that Manchester-based creative and Club member, Gracie Brackstone, had the idea to take on the government with an art, fashion and design exhibition called Art is Coming

Likewise, for Marciella Carr, a Manchester creative also featured in Dazed, the situation was ‘not giving’. Moving home after university, Marcie expected to return to Manchester a few weeks later. Amidst the cost-of-living housing crisis, it would be another four months before she could return. During this time, she created a short film named Lowna Lee. The project follows an imagined relationship between Marcie and a paper mâché doll, ingeniously named Lowna Lee (pronouns unknown). When asked about the film, the creative recalled the feelings of an era of dislocation in between houses: “all my mates had their jobs lined up and people from uni were moving here, there, and everywhere. I was just like oh my god, I can’t even find a flipping house”. Out of a challenging crisis, a concept (and wholesome paper mâché relationship) arose. “Lowna Lee was just this light-hearted piss take out of my relationship with loneliness and how it manifested itself at that time.” What emerged was a wonderfully funny and colourful film.

For both artists, while the crisis inspired concepts, it also resulted in practical constraints. Both Gracie and Marcie highlighted the difficulties of balancing creative output with time available to do so, particularly when working to pay for rising living costs. For Gracie, when she’s not creating, she notes that “I have this real thing of guilt. It can feel challenging doing little by little. I don’t want to fall off. I just want to be creating, though that’s my own thing”. While recognising that this sense of guilt is an internal “thing”, it seems that the feeling is shared among artists living through the crisis. On her part, Marcie exhibited a similar sense of guilt. When asked what people can do to engage with her work, she joked, “I’d have to put out work first!” Undoubtedly, this deceleration in creative output is the result of working longer hours in hospitality to keep pace with heightening costs. She adds, “I personally struggle with this one because are you creating your work to be perceived or are you creating for yourself? It’s tricky. I think just because you aren’t publishing things it doesn’t make you any less of a creative”. As much as these responses signify an individualised sense of guilt about time spent creating, they also speak to broader pressures of time and everyday demands.

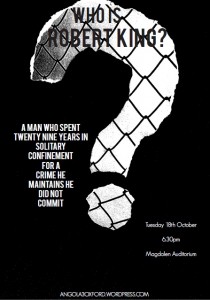

Besides time, both pointed directly to the economic strain that the cost-of-living crisis has placed upon many creatives. Carr highlighted the link between creativity and access to resources, noting that “creative materials themselves are really expensive and I think I took that for granted at uni. I was from a single parent income, so I got a bursary, which meant that I was able to invest in materials. Whereas now I don’t have that it isn’t as easy to create projects”. When asked about the biggest challenge facing creatives in the cost-of-living crisis, Brackstone summed up the answer in a single word: “money”. She continued, “When you’re an emerging artist you need money. I got let off my job in October and I’ve just been bar shifting it since. It meant that I had to sleep on my friend’s sofa for two months, but thank god I have my community, people who will do stuff to support me”.

Even so, the two artists have navigated the challenges of the crisis in endlessly innovative ways. Circling back to an early morning ride to work, when an unassuming Gracie had the idea for Art is Coming, she had no inkling as to how successful the collective would eventually become. “I was sat there on the bus like oh god, as if this is life. Who can be arsed? I was going round the roundabout like no—I’ve got to do an event about this.” She recalls amusedly, “I texted my best friend at 9 o’clock saying I think I might put an exhibition on about the cost-of-living crisis, and she was like ‘GIRL, do it!’ So that was that.”

Art is Coming is no ordinary collective. It was originally conceived as an exhibition for creatives to come together in a community, showcasing high-quality work in protest to the crisis, and the surrounding absence of adequate government measures taken to address it. It is fashion with a very political dimension. The focus on community brought Gracie and Marcie together, with the latter recalling that she got in touch with the former after seeing her promote the Manchester exhibition at Antwerp Mansion with a call out for submissions on the cost-of-living theme. As it happened, the crisis had already impelled Carr to create a piece, an anti-patriotic play on the Union Jack titled feeling blue, but not in the red and white kind. Marcie describes the work as a reference to the cost-of-living crisis and “the country being generally a bit rubbish”. The result was that individualised expressions of frustration and struggle were transformed into a powerful collective movement.

The success of Art is Coming in Manchester led to further instalments in London at VFDalston and a collaboration with Tate Liverpool for Eurovision in May 2023. The energy of the collective is undeniable. While continuing to grow, it still maintains the community spirit that was so important to Brackstone from the outset. After reaching out for the initial exhibition, Marcie recalls that it was who then got in touch with her to showcase Lowna Lee in the following London exhibition. This testifies to the ability of Art is Coming—encompassing fashion, art, and design to project a strong political message and to implement practical change by providing a community space for creatives in the cost-of-living crisis.

This brings us to the question of fashion and sustainability. Is it possible that there is a class component to the way that people perceive it—as either buzzword or a practice, and if so, what are the practical implications? A theme that figured strongly whilst chatting with Brackstone was the idea of resourcefulness. She shared, “I was having this conversation with this girl the other day—Maddy, a working-class designer from Rochdale—about a shoot I had where I was complaining about my £20 camera and wishing I had a nicer one. Then this girl I was shooting with said, ‘well no, you make nice work anyway. You’re producing stuff off a £20 camera that is going places anyway’” —by places, Gracie means a published photo-book, though she refrained to mention. She adds, “I sometimes think, how would things be different with money? But this girl said to me, ‘Do you know what, though? We are naturally more resourceful because we haven’t had the money. You have to work to find other ways of doing things’, which is so true”.

Natural resourcefulness is something that recurrently shapes Gracie and Marcie’s styling. Both referred to the need to buy cheap fabrics. Gracie noted, “I had so much fun creating these [looks]. If I had the money, I would be pulling from fashion houses, and it would still be beautiful of course. But would it have as much as a story?” Furthermore, the two also emphasised the role of safety pins, allowing them to recreate new looks from old material and spare on costs. Demonstrating this point, Brackstone notes, “I feel like for queer people especially you only have what is accessible to you—you cut a top in half and it makes a two piece. You use it a different way and it’s a scarf. It’s so mixmatchy”.

Interestingly, both underscored the emphasis that their Fashion Art Direction degrees had placed upon creating for impact, often in relation to sustainability. Gracie confessed, “It’s hard because in the industry right now, and through uni, you’re taught, ‘why are you creating things if it’s not to make an impact? Or if it’s not to change things or to be changemakers of the world?’”. She adds, “But I studied fucking fashion, I don’t know what the climate crisis answer is”. Evidently, the two rejected, to varying degrees, the idea of creating to implement large-scale social change. The buzzword ‘sustainability’ was curiously absent from all discussions about resourcefulness. The irony then, is that sustainability isn’t used as a buzzword in these contexts, but it is embodied in what Marcie and Gracie do daily, through their determination to continue creating high-quality work from what is available to them.

This isn’t to say that sustainability in the depop_drama sense can’t be a positive thing. When you consider the fact that 100 billion garments are produced per year, second-hand purchases become important. However, as this piece has highlighted, the sustainability buzzword can reflect a very middle-class way of thinking. If we consider alternative class perspectives, then sustainability becomes less of a question of second-hand purchasing power. Rather, it begins to reflect resourcefulness and meaningful engagement with materials or garments already available. Rethinking the buzzword places greater emphasis on resourcefulness and adds to our repertoire by informing better sustainability practices in fashion. Second-hand purchasing power might become more productive if we think in terms of how long we intend to wear garments for, and how we might re-use the fabric as trends change.

So how do talented creatives sustain themselves in a cost-of-living crisis? The short answer: it’s not about how much you have; it’s about what you do with what you have.∎

For more on Gracie Brackstone and Marciella Carr’s creative projects: @graciebrackstone @mars_mishmash on Instagram.

Words by Anya Athwal. Photos courtesy of Gracie Brackstone and Marciella Carr.