Alone in the House

by Leila Moore | February 4, 2024

No, I hadn’t left the downstairs light on. Had I?

I hang a few paces outside my doorway. Before this I was stewing in my bedroom. I could have been doing a million other things than rolling around on my bed, intermittently swapping phone, book and laptop between my hands, wondering if this was what it felt like to begin to go insane. The house was in a phase of rare emptiness, and I felt like writing myself into a grim sort of mood. World domination loitered outside my bedroom while I hunched over the keyboard, typing stickily, shedding clothes and words only half methodically—

That peculiar sickness of mid-morning—

hours of ten and eleven that die

prolonged, noisy, attention-whoring deaths,

enrapturing us who clutch our collection of

importantly dressed tasks;

this affliction has crept across the long

limbs of our whole days,

our nights,

as heat holds the country in the crook of its arm

for nothing but amusement, its own

pitiful moth housed in a jar.

The days may be sun drowned

but night arrives and practises its

forgetting upon us;

gone are the easy charms of the sun,

all one could know is heat

rolling in, a freak tide begotten by nowheres,

dappling damp skin like unwanted fingers,

gleaning collections of almost-smothered infants.

I’m not sure about this. But

The malice must go somewhere.

Maybe this isn’t working.

I swing untethered, scaling the curtain-call of night-time and

life just keeps going

and going,

shredding itself to pieces

before I even brush against it,

fingers watching while it rips itself apart, merest suggestions

of myself

setting off the sickeningly stunning motion of existence

as water cries out the colours of a rainbow

against all will.

Well. Now you just feel worse.

Once the writing was finished I stared at my wall and thought about how writing wasn’t really writing anymore because it was all typing. Typing was faster than handwriting so that’s why I preferred it, which wasn’t inherently bad, but nonetheless gone forever were the days of scribbling with a pencil until it was blunted and your hand ached and getting up to sharpen it only wasted time. I didn’t like it but that didn’t mean I couldn’t miss it. My computer screen had imprinted on the wall; a halo in the shape of a rectangle stalked my vision until I blinked it away.

I should probably get some water.

So now we meet ourselves here again stood in the door, frightened by my imagination, and I’m home alone. The key to the whole problem though is staggeringly simple, and it isn’t reminding myself that scary stories aren’t real and no, true-crime doesn’t bow to that decree—but we’re going to ignore that for practicality’s sake. The key is putting a shirt on.

Because what I neglected to describe about my house is that a few paces outside my bedroom door is a mirror, and in that mirror I remembered myself as almost entirely naked. Because it was thirty degrees, and it’s not weird because I’m alone in my own goddamn house, alright?

Actually not alright. Because your naked body exponentially increases chances of a man standing in your kitchen donning a comically terrifying mask, who wouldn’t have killed you if you had just put your tits away. This man would be in my kitchen, or peering still as a stone through the open window, or the man would be a camera propped up in a different house’s window, drinking it all in. And his face was always painted white. The video of me making nearly-naked-tea in the kitchen would be posted (didn’t it always have to be posted?) and I would nearly kill myself at the cruelty of it all. Only nearly, though, because then I could write a really brilliant, scathing article about my experience, which would make the front page of a suitable literary magazine. Maybe even a book.

I shed my nightmare of literary fame by donning a comically oversized t-shirt that I can already feel myself sweating in as I trudge down the stairs. It makes the bogey men and rapists disappear, at the very least from my mind, and almost definitely from the house.

While the kettle is boiling I ask myself if murderous thoughts like this would have strayed my mind if I hadn’t been naked, if I had been wearing just a regular pair of pyjamas, or if I wasn’t a woman. Or if I wasn’t a woman who was weak, or if I was a woman who had a dog that could kill people. Probably? Honestly, probably. I wish I could make it all about gender and my tits but that would be too simple—I would probably have been spooked by something even when wearing my biggest pair of chastity-belt-pyjamas. My killer dog would turn its appetite to me, with no murderers to snack on. Humans have to have a little bit of fear, when the house is empty and it’s dark outside—it’s the imagination’s primary job to colour in all those blank spaces, and if you don’t know what’s stood outside the door then it must be something that wants to smother you in your sleep, if it’s going to be anything. Not to be essentialist, but we’ve all thought that for little to no reason at least once.

So it was incredibly human, not womanly of me, to turn my fear fantasy into actual fantasy, which funnelled my nearly being raped and murdered into an arc which resulted in me winning the fucking Booker prize or something. And people argue optimism isn’t inherent to the human condition.

The tea had brewed and I had convinced myself that my fear wasn’t political. But back in my room—the demilitarised zone for female nudity—I thought of a scene from The Fall (2013). Jamie Dornan breaks into a woman’s house a few days before he kills her and lays out a pair of lingerie and her vibrator on her bed—a warning, a greeting, an invitation to stick around. Come and see. So the murdered sticks around because it’s her own goddamn house, alright? She owns it and she’s going to win this perverse competition from the neighbourhood weirdo whose only joy in life is rifling through strangers’ underwear drawers. No putting a shirt on, no throwing away the vibrator—my house!

After Jamie Dornan kills her he paints her nails a deep red.

I think about how many times I have rehearsed these encounters. Scores more than I have dreamed of my wedding, which little girls aren’t really meant to do anymore. Yes, the instance of fear may be pure, spurred on by the simplicity of instinct. And it may be eternally unavoidable, the price we pay for the many blessings of imagination. But the well-trodden paths of my most aged fear-fantasies are surely avoidable, because, unlike instinct, I can look at its source. It can be explained without science, I chronologise it because the fear is nothing but a story we have been told again and again and again. We tell ourselves about women getting killed so often that now we can even laugh at it: watch Scream together and go home embarrassingly afraid.

I choose not to hear the patriarchy banging down my bedroom door when I put clothes on to walk to a deserted kitchen. My brain latched onto nakedness as the closest possible antidote to my fear, is all: pyjamas as a talisman. Being scared is inevitable, looking for quick solutions to it even more so. But. It’s our monsters that say the most about us, mutating through the course of our lives to become a little more specific than darkness, pain, heights. And mine, many people’s, has always, will always be—

Alone In The House.

The Man.

∎

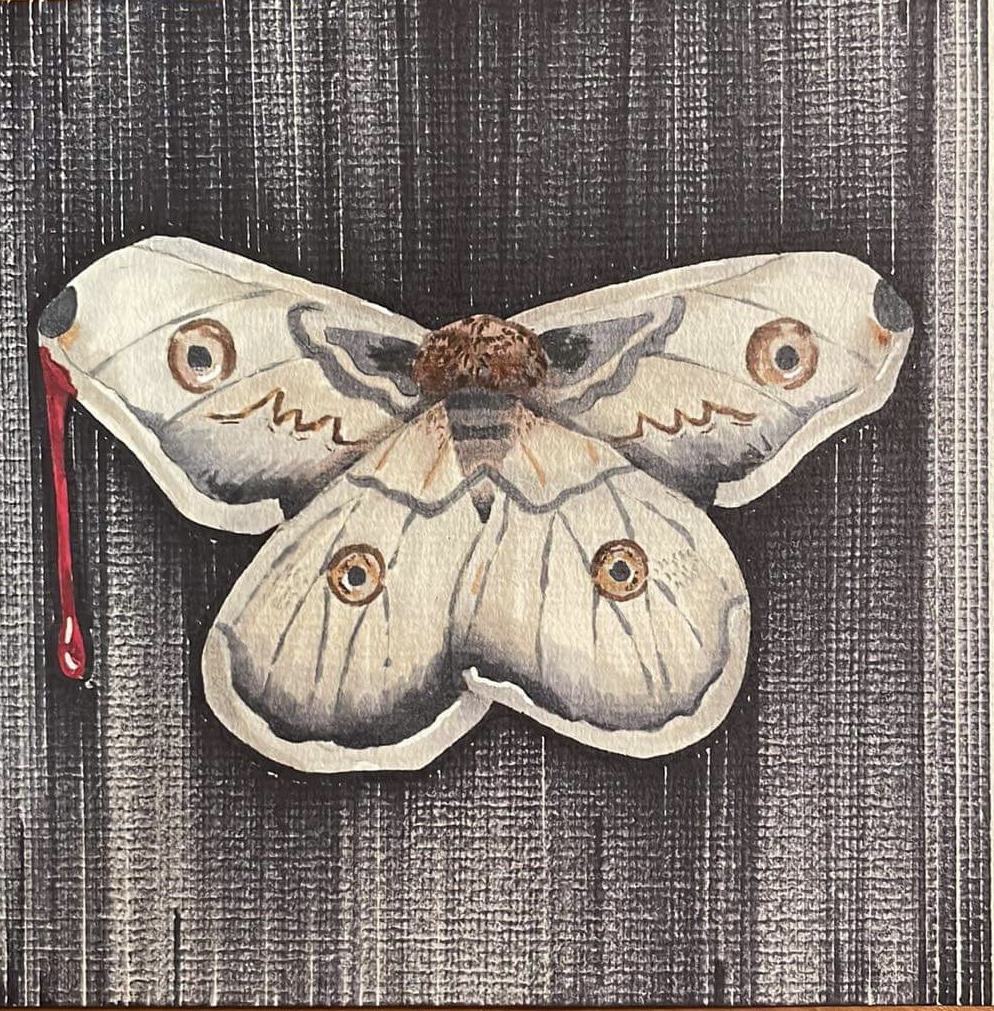

Words by Leila Moore. Art by Indiana Sharp.