A Portrait of the Artist as a City: Evelyn Hofer at the Photographers’ Gallery

At some point in her life – and no one who quotes the maxim seems to know quite when it was – Evelyn Hofer outlined a philosophy that has fashioned the way many creatives see their medium: “In reality, all we photographers photograph is ourselves in each other – all the time.”

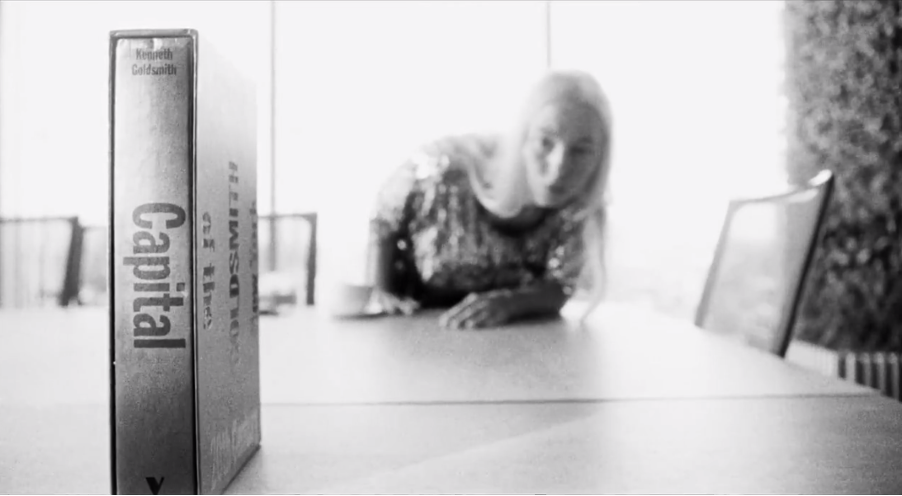

It is one of the few obvious traces we have of the artist’s voice. Described in the 1960s by critic Hilton Kramer as “the most famous unknown photographer in America”, Hofer’s public image is conspicuous in its inconspicuousness. Photographs of her are few and, in the ones that exist, she comes across as ironically camera-shy. Smiling, she averts her bespectacled gaze from the lens that is pointed at her. She is more at ease behind the camera. Untroubled by Kramer’s assessment of her, Hofer committed herself to privacy; even close friends of hers have drawn a blank when pressed for intimate details.

The pronouncement that her personality occupies so fundamental a role in all her own photographs is thus a startling assertion of identity. Hofer’s work is suffused with the question of her presence in it; it is rich with character, but a distinctly enigmatic one. Her placement behind the camera contains a paradox, for she simultaneously obscures and – if we are to listen to her declaration – reveals herself. The Photographers’ Gallery’s retrospective plays with this riddle, divulging no sign of the artist’s face; even in Self-Portrait with Gigi(1974), it is fittingly veiled by a small camera. It is the photographs themselves that are proffered as Hofer’s articulate biographers. If we are to catch a glimpse of the artist, it is through the gaze of the subjects, who stare at once at us and her.

Phoenix Park on a Sunday, Dublin, 1966

The exhibition is the first solo showcase of Hofer’s work in the United Kingdom, itself a testament to her nebulous personal legacy. It benevolently assumes for its attendees a level of unfamiliarity with the artist’s style, and seeks to remedy it. Evelyn Hofer embodies a departure from trend, I was informed as I began to scan the introduction that occupies the first wall of the show: she stood in contrast to the spontaneous photography style of modish contemporaries like William Klein. Where his work is dynamic, hers is reflective; where he favoured low-weight Leicas, she wielded a large-format 4×5; where he used monochrome, she preferred a world flooded with colour.

By the time I reached the end of the paragraph, I felt smugly assured of my mastery of the subject matter. It was to my surprise, therefore, that I turned around to a room dominated by black and white. Hofer’s mercuriality was made immediately apparent.

The artist travelled a great deal throughout her life, which began in the tranquil university town of Marburg and came to a close amidst the vibrant stir of Mexico City. Displacement from her birthplace, necessitated by her father’s ardent antipathy towards the rising Nazi party, kickstarted an unending journey that would shape her career. Much of her work resides in photobooks dedicated to various cities across Europe and the United States. Within their pages, Hofer’s conversance with these spaces is preserved through landscapes and portraits alike.

The exhibition is duly organised according to geography. Its curation is not heavy-handed, nor does it need to be – it is clear, without signage, when one encounters a new location. Each city Hofer captures is possessed of a distinctive and tangible personality, actualised through her manipulation of colour and composition.

The images that foil my supposed expertise are, primarily, of London. Perhaps though, to employ the word ‘London’ suggests that the photographs summon a coherent image of a unified space. Not so. Hofer’s London is eminently plural: it contains within it several Londons, each representing one of the social microclimates of which the city was composed. Two black children peer out of a curtained window in Notting Hill Gate in one snapshot; in the next, elderly white warehousemen stand flocked under a bridge in wintry Southwark. London is empty in Blackfriars’ Station, London (1962) yet it is awash with conversation in Lorry Drivers, Tower Hill, London (1962).

One photograph’s London is, as its title suggests, not Hofer’s at all; it is Shakespeare’s London (1962), a capital whose old-fashioned buildings seem to frustrate movement towards modernity. Dark of brick and grey of sky, the image’s palette lends it an air of Dickensian urbanity, too. A glance along the wall reveals yet another iteration of the city: the gallery space yields to a large window through which one can see the bustle of modern-day Oxford Street.

Can these photographs be ‘of’ Hofer herself; is she somehow externalised, and projected into the scenes she captures? Perhaps there is something perplexingly intimate about seeing a space through a stranger’s eyes – Hofer does not show us readily accessible landmarks, but rather guides us through backstreets, makes us privy to specific interactions. So too is the cityscape characterised by the stillness that has come to be seen as her hallmark; a tourist ambling through London in the 1960s would not have encountered the same metropolis that Hofer offers her viewers.

Husband Bridge, Dublin, 1966

Walk on, and one becomes immersed in the sober hues that define Hofer’s rendering of Dublin. Once again, inanimation extends beyond subjects like the Trinity College library and James Joyce’s death mask. Gravediggers, hands resting on spades, pose solemnly for Hofer’s camera; so too does the Master of the High Court, the tendrils of smoke coming from his cigarette the one defiant indication of motion. She even seems, in School Kids on Henrietta Street, Dublin (1966), to have accomplished the feat that most photographers can only dream of: twenty or so children sit still, with eyes open and directed at Hofer’s lens.

In these portraits, the rapport that exists between artist and subject is palpable. Hofer was not shooting these photographs on the sly, as contemporaries like Robert Frank were known to do. Rather, the images are a kind of collaboration: looking at them, one can almost hear the conversations by which they were preceded. “I tried to meet the person first, to show my respect and desire to take the portrait wherever he or she would prefer”, she once explained. This openness dictated her artistic process: “one reason I like to work with a big camera is that I don’t like to spy on people”. She affords her landscapes equal respect, treating them as quasi-human. In Arteries, New York (1964), the city’s twisting highways are transformed into blood vessels; by extension, the city itself becomes an organism.

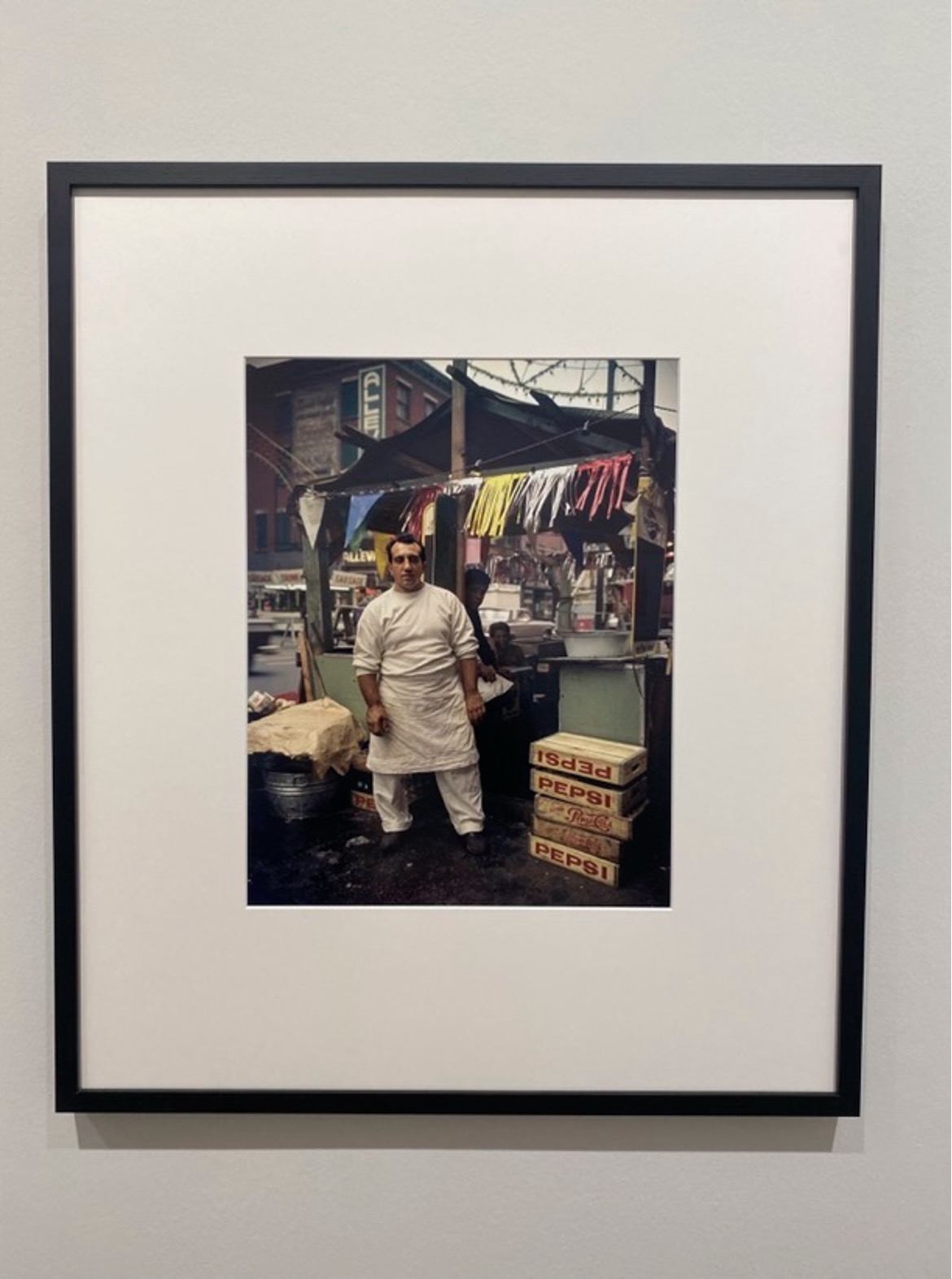

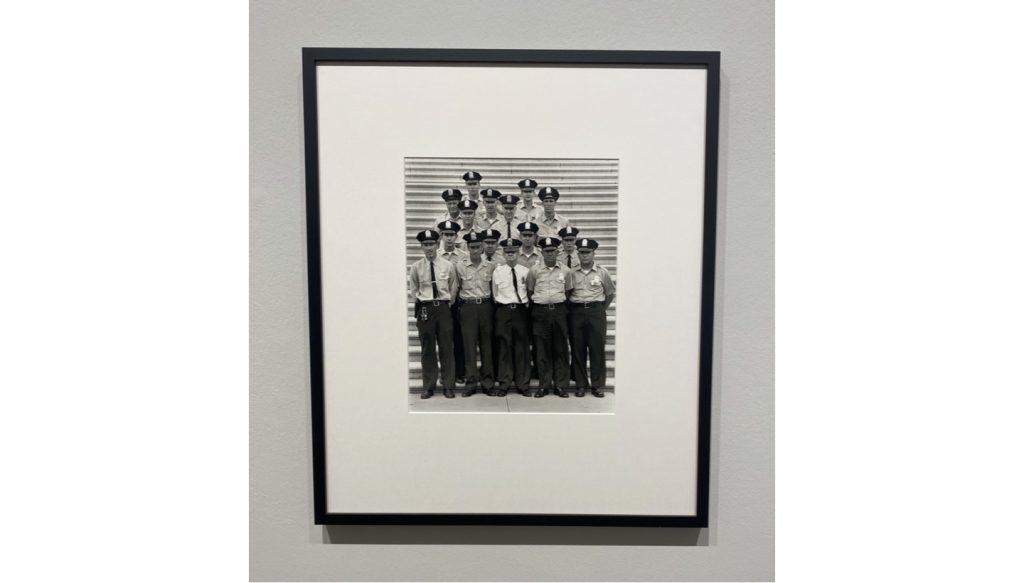

Hofer’s approach to her subject matter is almost scientific. If her cities are living beings, they are ones that are dissected and studied with meticulous care. In their foreword to Evelyn Hofer: Eyes on the City (2023), Rand Suffolk and Julian Zugazagoitia laud the “exactitude” with which she constructs her photographs. This quality is, perhaps, especially apparent in her Washington-based photojournalism. The tightness of the American political structure is visually replicated in works like The Joint Chiefs, Washington (1965) and Capital Police, Washington (1965): Hofer’s composition is precise and her subjects deliberately arranged. Even in New York, the city James Baldwin fondly described as “spitefully incoherent”, she imposes a sort of calm spatial order.

Capital Police, Washington, 1965

One would be hard pushed to argue that Hofer’s work was conceived to function autobiographically: the conceptual self-portraiture she admits to is rather an unnegotiable law of personal creativity. Regardless of intentionality, though, it colours her retrospective, lending new relevance to the idea of portraiture. Hofer captures people; she captures landscapes; she captures whole cities – in doing so, for all her privacy, she cannot help but capture herself. Examining the spaces she creates with her camera, one sees more than London, Dublin, or New York: one also sees the measured, ruminant, and sensitive person who wields the lens.∎

Words and images of photographs on display by Connie Higgins. Featured photograph: Hot Dog Stand, New York, 1963