Top G Diffusion Filter

by Alexander Archer | May 28, 2024

Andrew Tate. Dostoyevsky. Subterranean Homesick Blues. Couperin. Turbo-folk. Durex. Henry Fielding. Capital (by Kenneth Goldsmith not Karl Marx). Žižek. Ode to Joy. Dichtung. und Wahrheit. Zoom virtual backgrounds. Deloitte. Jean Luc Godard. Uwe Boll. Snapchat. 25mm Cooke S4 Lens. Gold diffusion filter.

21st century hyper-referentiality has finally made contact with European art cinema, and the result is something to behold. Radu Jude’s new Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, ‘Nu aștepta prea mult de la sfârșitul lumii’, (which premiered in Locarno in August, has only recently been let out of EU hell for public release in the UK) is well aware it exists in the age-of-the-short-form-video, and that the name of the game is REFERENCES. The film, an capturing a day in the life of an overworked/underpaid video production assistant called Angela (Ilinca Manolache), is dead set on tackling the hyper-referential, informationally overloaded passage of the human mind into the digital culture of the roaring 2020s. Here is a world now unthinkable without the collective unconscious of TikTok, or the transhuman visual economy of Snapchat filters, and this is the first film I’ve seen to properly commit to embodying that chaos in its own form.

Angela’s day consists of 16 hours of exhausting labour for her production company, hours mostly spent driving around Bucharest to audition workplace accident victims for a “safety at work” video. Along the way she weathers inconvenience, sexism, and traffic with mordant resignation, running the occasional personal errand too (a nap, a quick shag). As the video applicants get increasingly maimed, it becomes clear that the multinational company behind the video is very much also behind all the debilitating injuries. Blithely telling their employees to “always wear a helmet” isn’t going to make their crumbling, Ceaușescu-holdover factory any less of a death trap.

The main film’s main narrative, then, is one of economic exploitation: Angela’s, the workers’, Romania’s. Jude pursues these threads of critique with a thoroughness that often clashes with the film’s stylistic commitment to an overwhelming and illogical stream of cultural signifiers. Angela’s day is frequently juxtaposed with clips from a kitschy 70s communist film about a no-nonsense female taxi driver, who jets as if from one still to another while she encounters Romance and Injustice on the richly film-grained streets of Bucharest. These sharply contrast the cool black and white which Angela’s life is filmed in. At the other end of the spectrum, there are the bizarre, “satirical” TikToks Angela makes to blow off steam, in which she films herself with a cartoon Andrew Tate filter and spews exaggeratedly chauvinistic anecdotes about bitches, hoes, water parks, etc. Patriarchal aesthetics first as tragedy, then as farce.

The problem with Jude’s barrage approach is that his namechecks mostly end up as Yes, it’s a funny clash of high and low culture when Andrew Tate disses Miss Jean Brodie, but it might just as well be Mr Beast dissing Esther Summerson. Jude wields his references with the ease of a director unwilling to engage with the full weight of the content attached to them, and the jokes (and the critique) seldom get very much further than this basic juxtaposition effect.

Every now and again it works really well: Jude gives Nina Hoss’ Austrian PR executive character—a 21st century personification of indifferent, corporate evil—a perfect bathos by naming her “Doris Goethe”. The scene where a particularly incongruous Zoom background enables her disembodied head to float menacingly over a table of subordinates is a perfect example of how good Jude is at extracting surreal comedy from the digital havoc of contemporary life—the film really can be very funny! On the whole, though, Jude’s enthusiasm for proper nouns results in a film (nearly 3 hours long) which feels large, but far from dense.

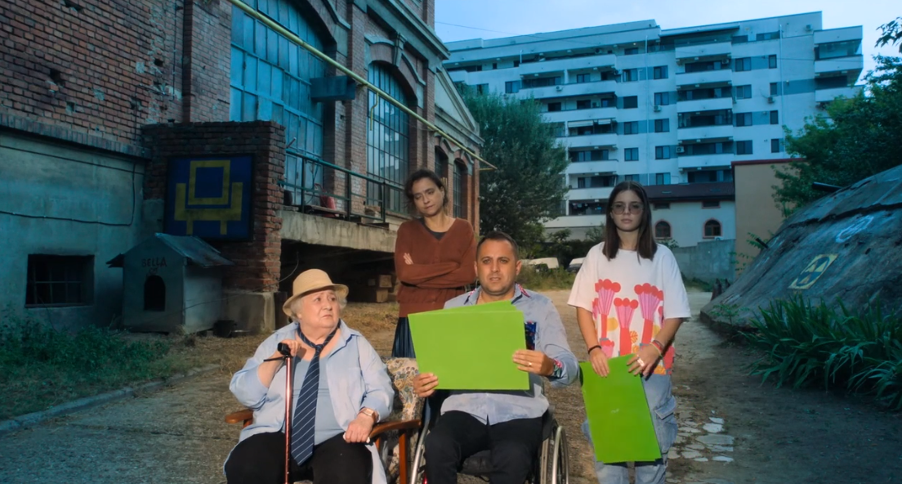

Jude’s critique is at its most effective when he hunkers down and allows himself to become nakedly didactic. The film’s high point is to be found in the austere, demonstrative clarity of its second act, in which the “safety at work” video is actually made. Filmed in one, continuous take, we see the scene through the eye of the camera they’re using in the film (making for a striking 21st century take on the principle of unity of place), which looks on unblinkingly as the story of Ovidiu Pîrșan’s crippling workplace injury is gradually reconstructed into a self-flagellatory piece of corporate propaganda. At every step, a complicated chain of power behind the camera reinterprets Ovidiu’s narrative and weaponises it against him, in a process so decentred that it absolves any individual person of wrongdoing. Although it’s a bleak note to end the film on, Jude’s discursive account of the processes behind this systemic exploitation hints at the possibility of understanding, and perhaps even reversal. There’s a very real anger to the film, which isn’t content with merely bearing self-congratulatory witness to such injustice.

At times, Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World can represent overly slow viewing. The film’s insistence on stretching out each of one its ideas to its painful, airless conclusion can makes for a dull time, even if you’ve got the knowledge of experimental cinema to know what the hell kind of tradition Jude is bouncing off. Expressing the often desperate tedium of everyday life means subjecting your viewer to a certain amount of it too. The film is more contemporary than any other I’ve seen, but in being so seems to identify the limits of its own relevance: in the internet age, what’s the use of a work of art which has figured out how to use its own dinosaur medium to half competently ape the effects of Instagram and TikTok? This is not even half the battle: Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World falls further short when confronted with the problem of saying anything particularly interesting about the now. As a document of our ever political, ever struggling-on life, however, it’s a triumphant success.∎

Words by Alexander Archer. Images courtesy of Mubi.