A Million Miles from Marvel

by isised | June 10, 2023

People study comics at Oxford.

Postgraduates, doing research on everything from Holocaust literature to the influence of Gothic texts on teenage girls, pore over the ever-expanding world of graphic literature, and get DPhils for it. Undergraduates reading English or Modern Languages frequently choose to study specific texts as part of their courses – and they’re welcomed by the faculties. Acknowledged masterpieces like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home are no longer seen as wacky or marginal choices, but as works of art and literature which invite and reward deep, analytical study.

As an English undergraduate at Merton in the 1980s, I wrote an article about the demise of Asterix the Gaul for Isis. It led to my one and only published work: The Complete Guide to Asterix (long out of print but eminently findable as a pirated PDF). And while I grew up in the shadow of Stan Lee, nowadays I explore sequential art that’s left superheroes far behind.

So, here’s a list of ten of my favourite graphic novels, each of which is both great fun and deeply creative. Some are pretty obscure. Some are internationally feted classics. Some are challengingly visceral. All are unique and brilliant works of art.

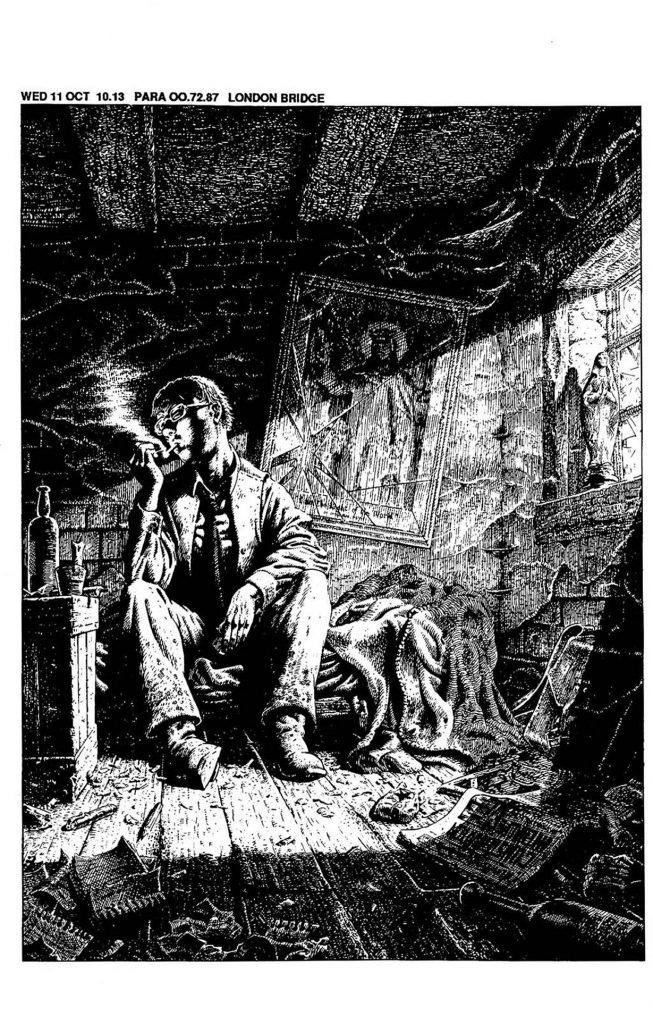

1. THE ADVENTURES OF LUTHER ARKWRIGHT – VOLUME 1

Bryan Talbot, 1982 onwards

The debate about which was the first-ever graphic novel will rumble on forever. But as far as the British comics scene goes, Luther Arkwright was there when it all began, and author/artist Bryan Talbot revolutionised the genre with this sci-fi steampunk epic. The plot is complex and elusive; the theme is revolutionary, anti-authoritarian, the death of Empire. And the art is staggering, with black-and-white etching closer to Hogarth than Homer Simpson. Talbot’s storytelling techniques are thrillingly experimental: there’s a sequence of pages that takes place essentially inside Arkwright’s head while he’s being tortured, and it ends in pure, white, empty space. Legendary comics maestro Alan Moore described Arkwright as “a crucial stepping stone between where comics were and where they are now”. I’d go further, and say Arkwright set the template for today’s adult graphic fiction.

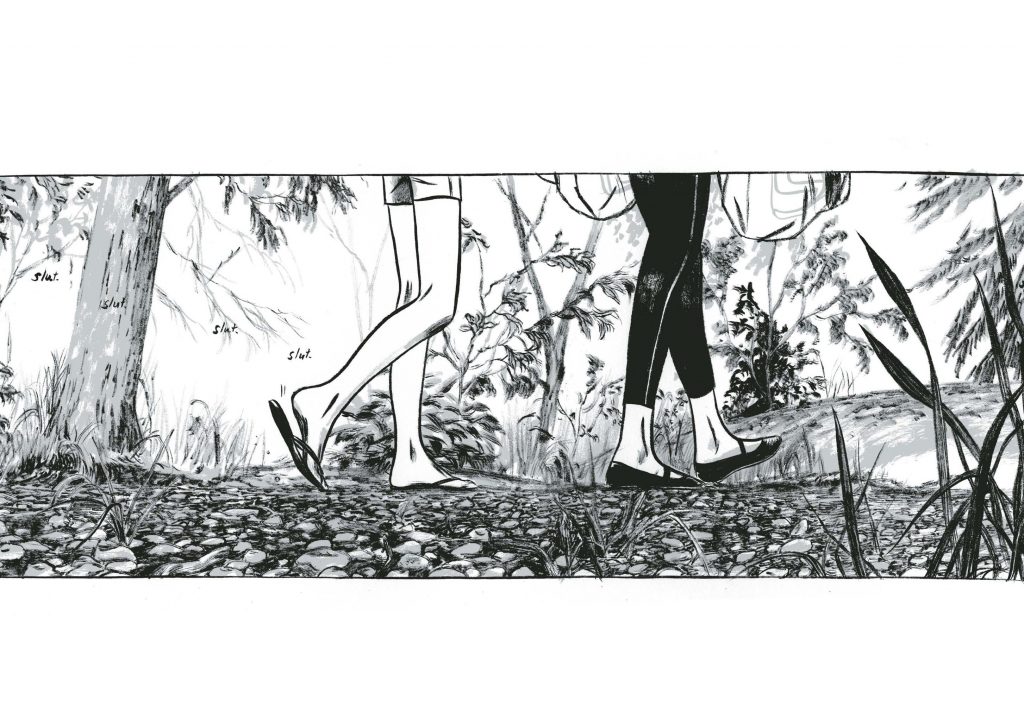

2. THIS ONE SUMMER

Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, 2014

Superficially, this is a coming-of-age story about two teenage friends, Rose and Windy, who meet up every summer in a remote little beach town in the USA. Over this one summer they begin to explore their sexuality, and are forced to grapple with traumatic family secrets, mental health problems, unwanted pregnancies, and the prospect that their innocent world will never be the same again. Jillian Tamaki’s drawings somehow capture that sense of a developmental cusp: monochromatic and sketchy, with hints of subtle detail and a gentle wash of cool, reflective blue. You can almost hear the lap of waves, the crunch of twigs, and you can sense the nostalgic warmth that signals the end of summer. If Arkwright’s plot is fundamental and obscure, This One Summer’s is almost incidental and evanescent… until the shattering finale.

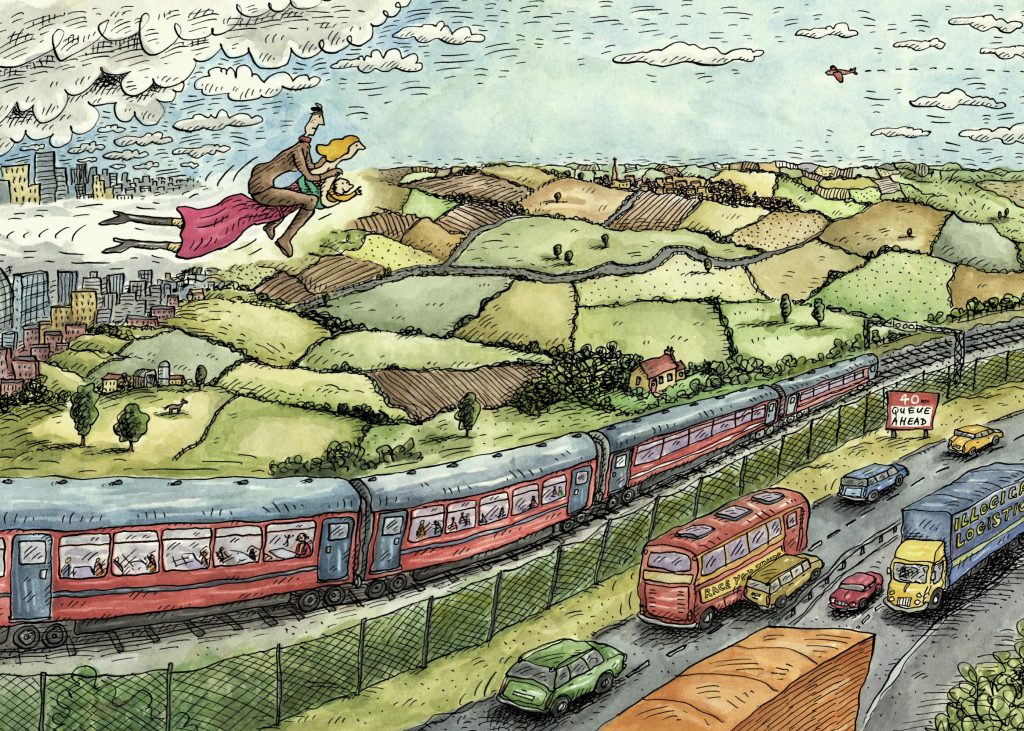

3. DRAGMAN

Steven Appleby, 2020

Steven Appleby is probably best known as a prolific cartoonist for various British and European newspapers, but she is a lot more than that. Her work in animation, cartoon, graphic novel and even hospital mural captures the sense of turmoil, self-doubt and fear that lurks beneath our respectable exteriors. Her humour lies in the fact that she recognises and illustrates the absurdity of that hidden paranoia. For me, Dragman is the masterpiece of Steven’s career. It’s a hilarious (but at the same time deeply moving) story of an innocuous everyman called Augustus Crimp. Augustus gets superpowers when he puts on women’s clothing. In that state, he can fulfil his potential and save the world – while enduring mockery from other superheroes. The metaphorical link with Steven’s own life is so naked and sincere that it completely charms you. At one point, Augustus, complaining about the sobriquet Dragman, says: “Dragman? That’s wrong. I dress as a woman, but I’m not doing drag. If anything, I’m trans… I think. I’m really just trying to be myself. Um.” The awkwardness and honesty are reflected in the shaky lines of Appleby’s art. It’s taken forty years, but this is one individual who has finally found themselves.

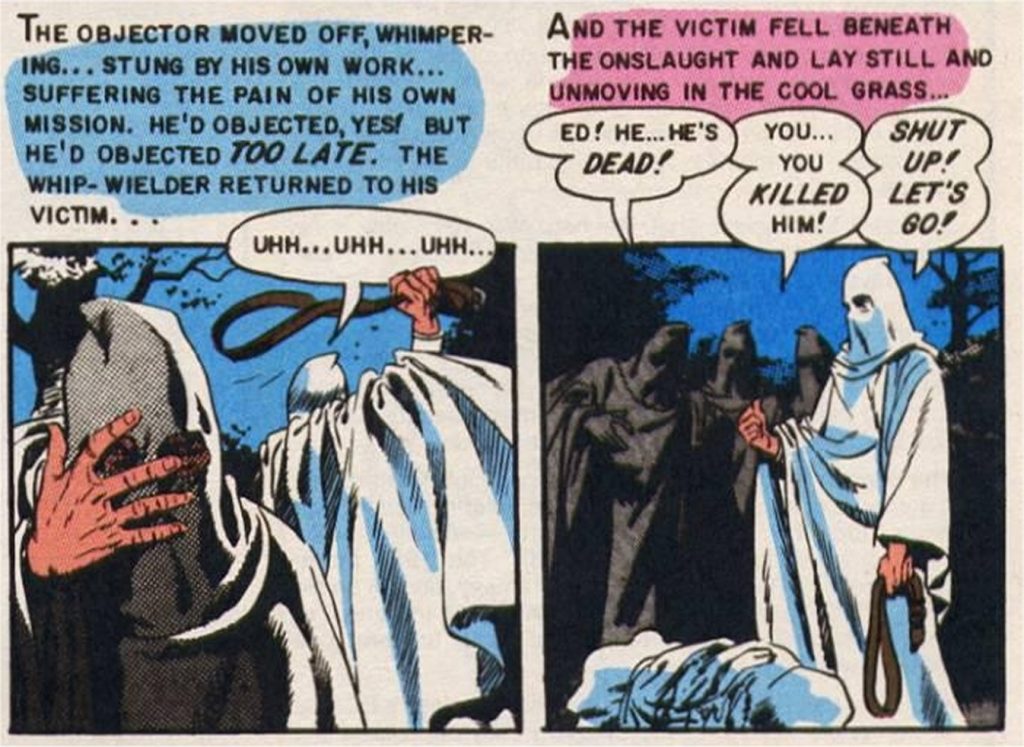

4. EC COMICS – THREE STORIES FROM THE 1950s

‘The Master Race’, Al Feldstein, Bernie Krigstein, 1955

‘The Guilty’, Al Feldstein, Wallace Wood, 1952

‘The Whipping’, Al Feldstein, Wallace Wood, 1954

If you don’t know about EC (standing for ‘Educational’ and later ‘Entertaining’ Comics), they were a publishing house that flourished in the late 1940s and 50s, issuing a broad range of titles, with lots of crime, horror, science fiction, and war stories. What distinguished them, however, was the morally principled and (in those days) extremely minority view they held on matters such as equality, racism and political honesty. Their stories came out before the murder of Emmett Till, and before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, when 96% of Americans believed mixed-race marriage was wrong. EC challenged widely held beliefs about interracial intimacy by calling upon readers to question their own prejudices. For his trouble, EC publisher William Gaines was cross-examined by the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, and ultimately EC were forced to tone down their output by the creation of the Comics Code. But they inspired a generation of counter-cultural young Americans. The Master Race is one of the first comic-book stories to deal with the Holocaust, as a former Nazi death camp commandant living in New York sees his victims all around him. The Guilty is a contemporary story of police brutality (and its accompanying cover-up) against black teenagers. And The Whipping is a superb morality tale of a group of white supremacists whose fear of Mexican boys going out with their daughters leads them to acts of horrific violence. Unforgettable, and for its time, astonishingly courageous.

5. FLEEP

Jason Shiga, 2002

There isn’t anyone working in comics quite like Jason Shiga. A maths major when he was at university, he is obsessed with patterns, solutions, puzzles, and logic. People? Not so much. In fact, the main character in almost all his books is identical and is normally called Jimmy – not because it’s the same person, but because identity and appearance for Shiga are simply not that important. They are secondary to the mathematical deduction processes channelled through the minds of his deceptively simple drawings. Shiga has created a number of astonishingly complex interactive comics. Meanwhile is an amazing experience, simultaneously puzzle and existential nightmare, but the one I’m choosing is Fleep, a comparatively simple story that takes place with just one character, set entirely in a phone box that is completely encased in concrete. That description illustrates that, yes, it is once more a form of puzzle, as Jimmy (it’s him again) tries to figure out where and who he is, as well as why he is in this predicament. What I love about Fleep is that, despite Shiga’s determinedly emotionless outlook, ultimately a heart-filled truth struggles out of the story. And the minimalist restrictions of the scenario are a fantastic challenge to the artist. Best of all, Fleep is free to read online. Search, and you shall find.

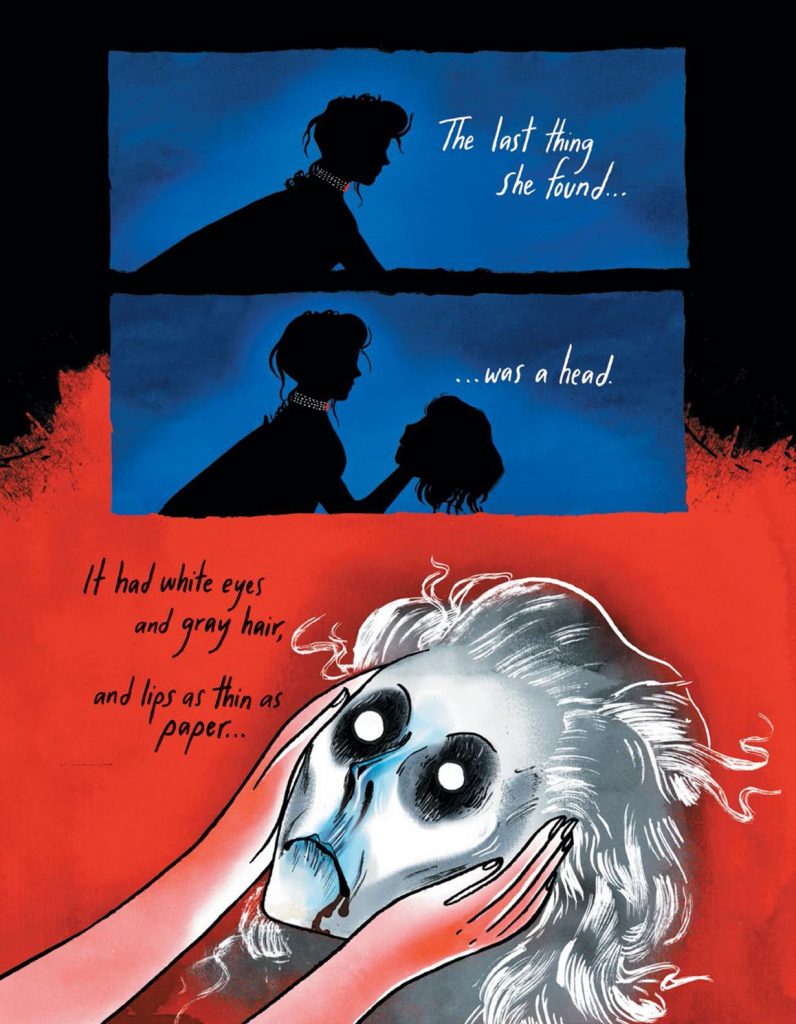

6. THROUGH THE WOODS

Emily Carroll, 2014

Emily Carroll stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Angela Carter, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Shirley Jackson as a purveyor of the finest feminist Gothic. Her tales pluck tiny tropes of buried fairy stories, and massage them into modern nightmares. And her images, like all the best horror, are both gruesomely dreadful and bewitchingly beautiful. This anthology of five tales is haunting in every sense of the word, created on a palette largely of black, white, and red, with occasional splashes of royal blue. Themes of guilt, gender, repression, and coercion balance the almost gleeful evil on display. My personal favourite is probably ‘His Face All Red’, about a girl and her older brother who seems to return from the dead. In Carroll’s work, each page is a single work of art, liberated from conventional ideas of panels and grids. The lettering is as much a part of the image as the figures themselves – a far cry from when writers used to glue speech bubbles all over the artists’ work. It’s a thing of strange beauty.

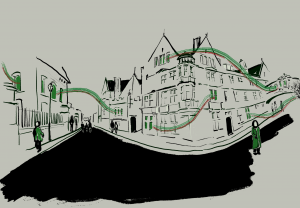

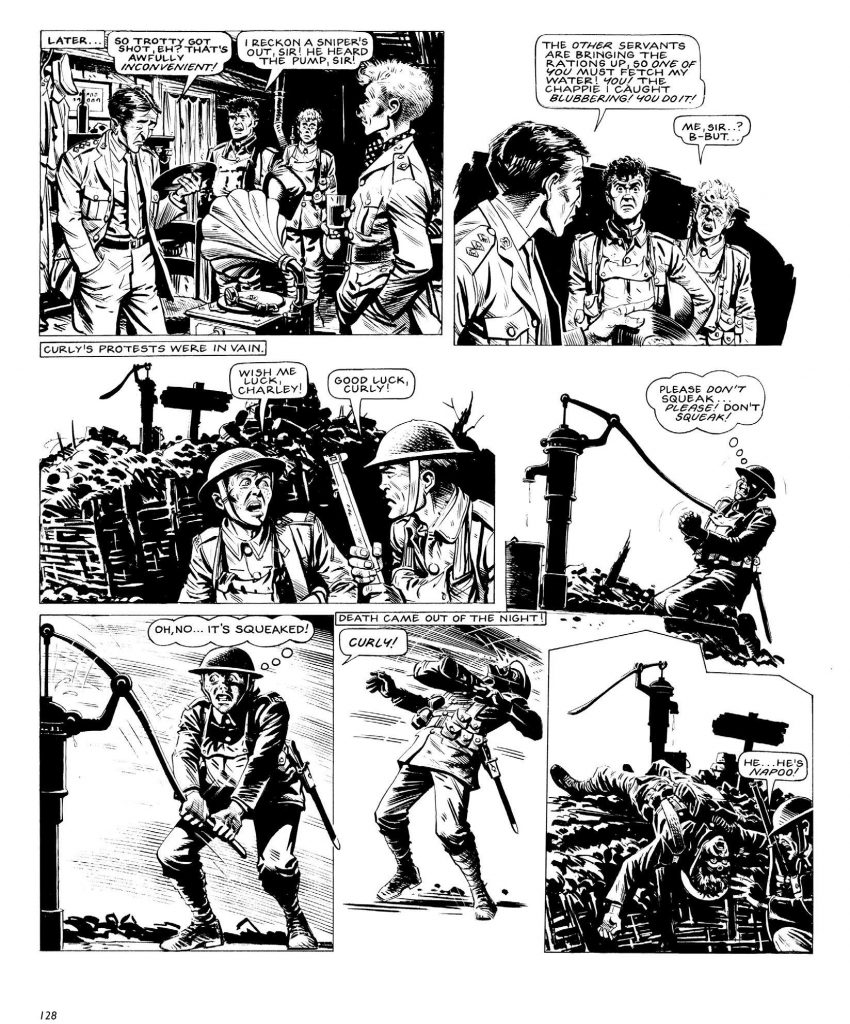

6. CHARLEY’S WAR

Pat Mills, Joe Colquhoun, 1979 – 1986

British boys’ comics were awash with World War Two stories for decades, with titles like Commando, War Picture Library and The Victor all featuring thrilling tales of derring-do. World War One stories were much less common. Charley’s War, which ran for seven years in Battle Magazine, followed an underage volunteer through the trenches of France from 1914 to the end of that terrible conflict. I missed it while I was growing up, but I found it a few years ago, collected in three gorgeous volumes, and I have to say: it is probably the greatest comic ever created in this country.

Why? First of all, Pat Mills’ writing is phenomenally terse, passionately driven (but full of dignity) and has a depth of knowledge that brings humanity to every character. It stands apart from every other war comic. Secondly, Joe Colquhoun’s drawings, each of them pure black and white, are stunning, uncompromising, and brilliantly detailed. (Colquhoun was in the Royal Navy during the War, so he knew how to depict both fighting and its impact on combatants.) Thirdly, and most importantly, Mills – who would go on to create the seminal British comic 2000AD – had a message to get across, and it wasn’t about the noble English against the evil Germans. The villains of Charley’s War are the English bullies, policymakers and businessmen who grounded down their own troops, kept themselves safe, and profited from the War (the accompanying image is a typical page). This is comics as class warfare, and it’s incendiary.

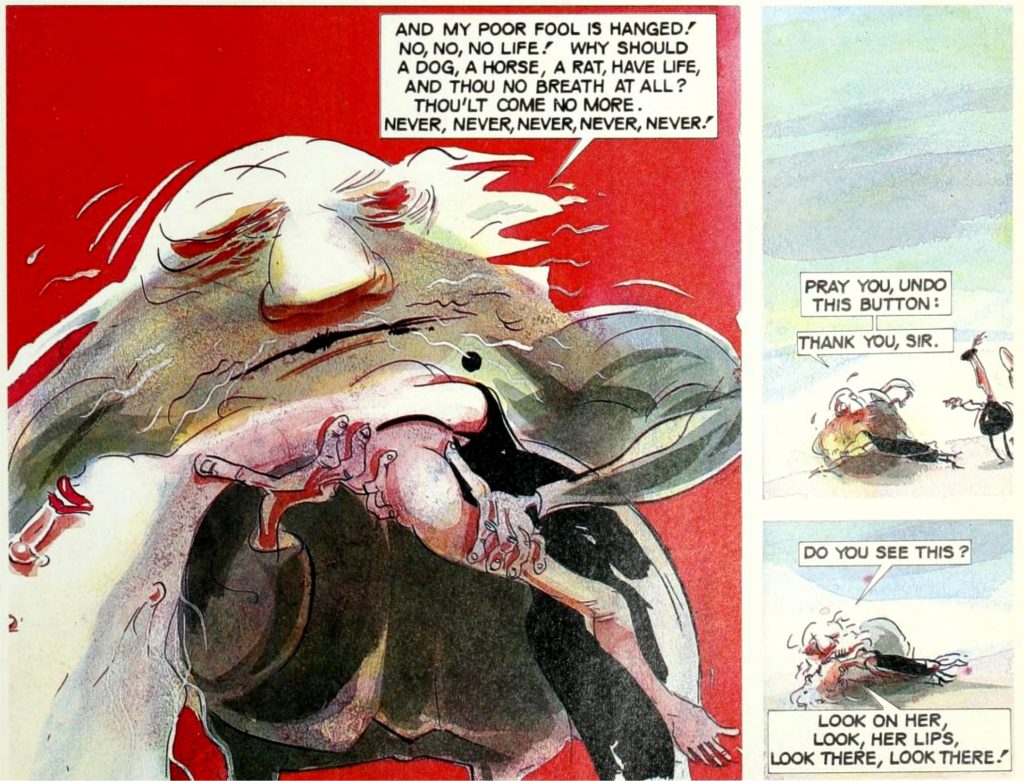

7. KING LEAR

William Shakespeare / Ian Pollock, 1984

‘Classics Illustrated’ and ‘Bible Stories’ have been responsible for some of the dullest, most two-dimensional comics ever created. Like Rupert the Bear,they tend to sit nervously somewhere between inoffensive illustration and unimaginative tableaux. Ian Pollock’s King Lear changed all that.

Pollock used to design amazing posters for the Royal Shakespeare Company, and after being involved with their phenomenal 1983 production of King Lear (with Michael Gambon as Lear and Anthony Sher as the Fool), he was commissioned to create a graphic novelisation of the entire, unexpurgated text. What he produced is, effectively, a performance of the play on paper – but a performance that could never take place in the real world. He brings the text to life with surreal imagery, grotesque characters, landscapes that appear and disappear from one panel to the next, and perspectives that jump from the massive to the distant. The Fool, whose speeches are so dense with imagery that audiences can hardly follow them, at one point literally juggles with the ideas that are coming out of his mouth. One of the most poignant moments in the book takes the almost inconsequential line of Lear’s from the death of Cordelia: “Pray you, undo this button”, and puts it in a panel all by itself, making Lear seem helpless and alone. It’s vicious, it’s tragic, it’s original, and it’s the best King Lear I’ve ever seen.

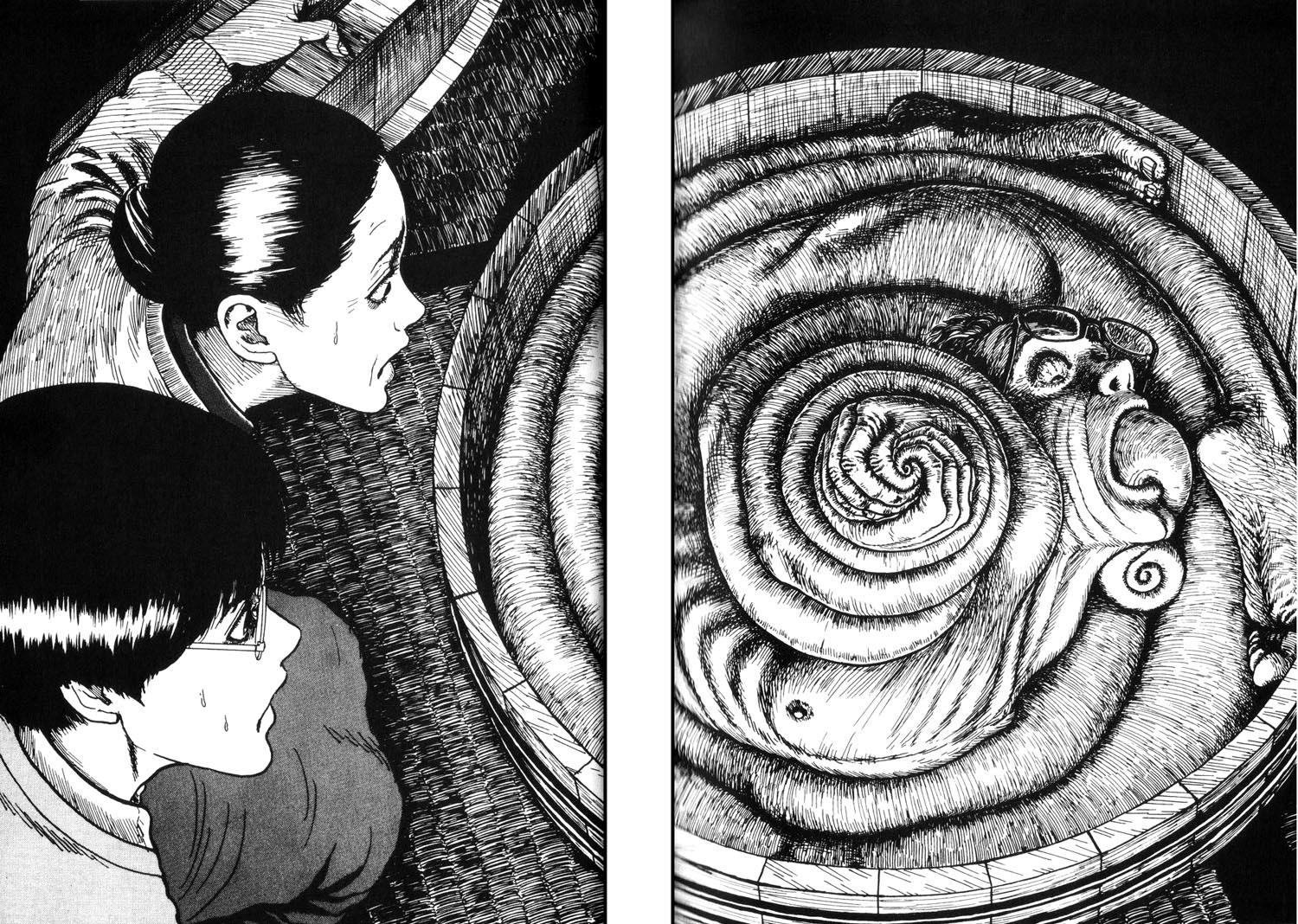

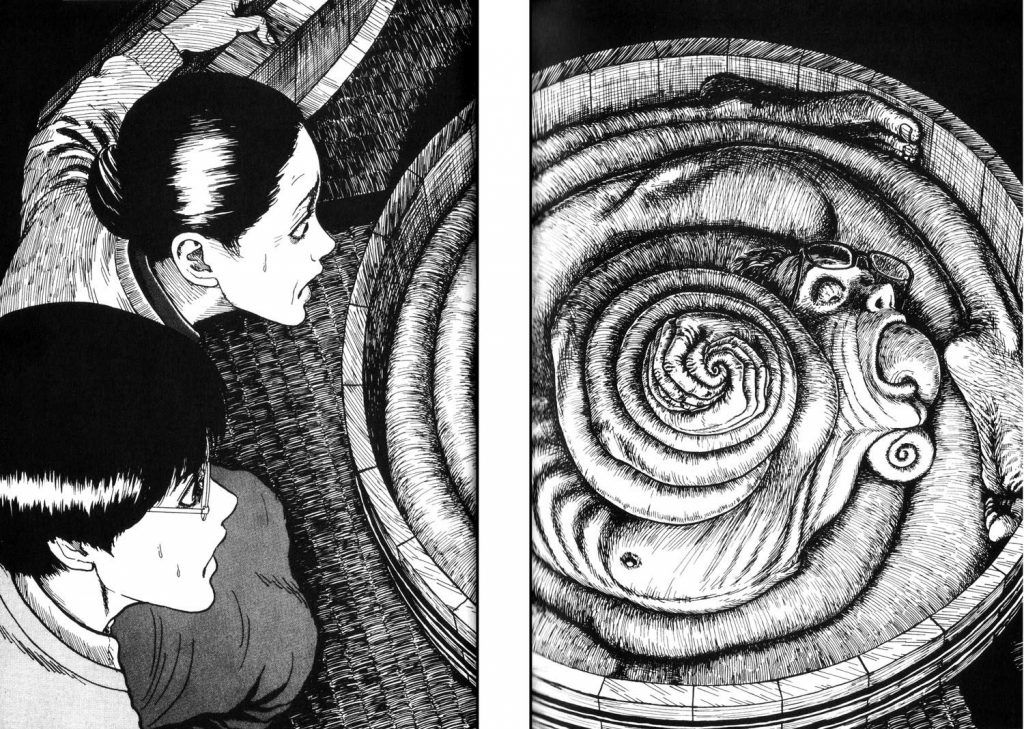

8. UZUMAKI

Junji Ito, 1998

Junji Ito is the master of Japanese horror, and if you’re not already familiar with his oeuvre, make sure you’re feeling calm and relaxed before you give it a try. His work is a perfect blend of two sub-genres: body horror and cosmic horror. The cosmic horror resides in the fact that the terrifying, supernatural events to which his characters are subjected seem beyond their control or understanding. The body horror is to be found in the impact that external force has on the characters’ lives – whether they are being pressed into solid rock in The Enigma of Amara Fault or whether, as in The Dissolving Classroom, the act of formal apology causes one’s schoolmates’ brains to liquefy and leak out of their nostrils.

Uzumaki is a phenomenal creation. Meaning ‘spirals’, it (literally) revolves around a community in which the townsfolk become obsessed with spirals. The sinister shape attacks, kills and dominates them in the form of typhoons, whirlpools and, in one particularly rebarbative scene, a specially made spiral box into which a man forces his own body. This clearly isn’t schlock horror: there’s a method in the madness, with social commentary never far from the surface. But what makes the whole thing unforgettable is Ito’s phenomenal draughtsmanship. Once seen, it will haunt your dreams.

9. MIRACLEMAN

Alan Moore, Garry Leach, Alan Davis, John Totleben, Mark Buckingham, Rick Veitch, 1982

I know I started this article by saying I’d moved away from superheroes, but we need to talk about Miracleman…

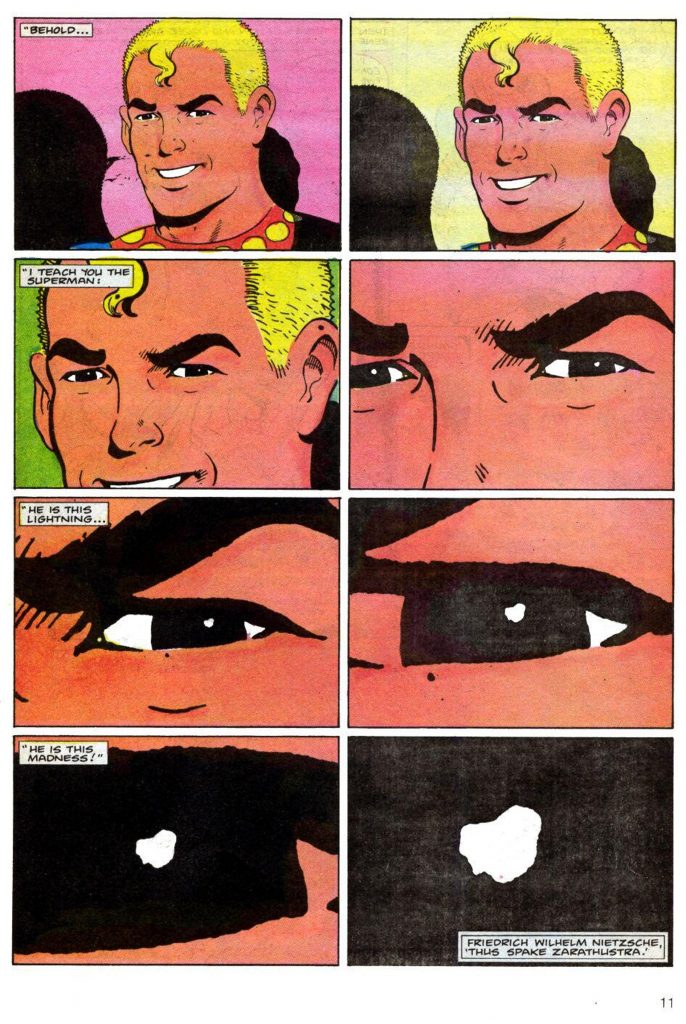

Watchmen may have been a global phenomenon, but it was not the first time Alan Moore had deconstructed the idea of the superhero. It all really started with Miracleman. In 1982, Moore took one of the flimsiest and most forgettable heroes ever invented, a cheap, 1950s, British knock-off of Superman called ‘Marvelman’, and asked one simple question: what if all this was actually real? What if, simply by saying the word ‘atomic’ backwards, a man could turn into an all-powerful being? The result was a devastating epic that broke taboos, questioned the role of heroism, and confronted head-on the principle that all power corrupts. Page 11 of issue 1 is a coup de bande dessinée that freezes on the smiling face of a two-dimensional superhero and then takes you into his Nietzschean soul. Issue 9 was the first time a comic had depicted a human birth in detail. And issue 15 features the brutal killing, in detail that would have made Hieronymus Bosch green with envy of everyone in London. By the end of the story, Miracleman’s inevitable triumph means that good prevails because humanity is scared into obedience: a distinctly uncomfortable and hollow victory. If you want to witness the moment that comics grew up, read Miracleman

.

Words by Peter Kessler.

Peter Kessler is the Magdalen Monday Movies curator and President’s Husband. He is also the Chair of the Lakes International Comic Arts Festival and Founder of the Oxford Comics Network, which promotes the study of comics and graphic novels at Oxford.