Dormitory

by Harry Lauchlan | January 11, 2023

Vogel frequently lies down. He listens to the other deposits of sound in his building spring to life and exhaust themselves. If there were often pockets of momentary turmoil erupting here and there – in the corridors or the plumbing – they go out too soon to take permanent shape. When alone, and with nothing else to keep him from sleep, Vogel tries to call Hass to mind and prolong the feeling of the world around him some moments longer.

The question sometimes strays out of his reach – whether he could have seen him more fully then – and each time he feels it recede, he tries to hold it back to his being, to make it burrow back.

Most of the time they spent together would have been during the walks back to the dormitory: wherever he’d been working that day, he’d finish and Hass would be stood there, waiting, often in some shade he’d found. Vogel struggles to recall what they would have spoken about, on that evening in particular or more sustainedly, each day sticking to the last. It seems improbable that they discussed the past, if only to avoid stirring the time prior to their acquaintance to the surface – though he is equally uncertain about what they could have said to each other about the future. The inevitability of their separation, even an indifference to it, was always present in Hass’s manner, even at his most affectionate – even if, Vogel accepts, neither could have put it that way at the time. He reflects that theirs was an intimacy capable of letting lie that which it couldn’t touch.

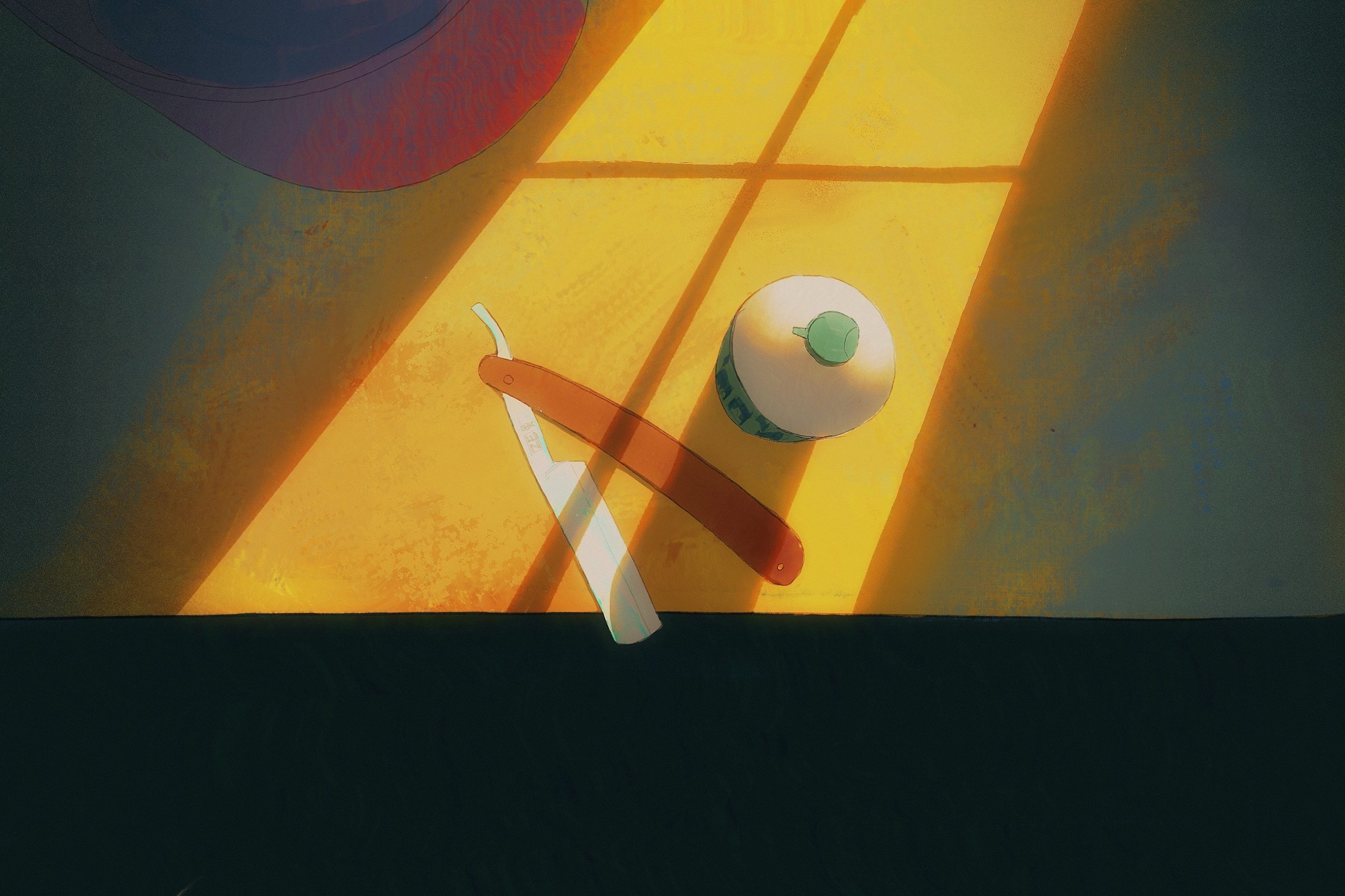

Were he to discuss the period in the company of, for example, friends, it would be the memory of his predecessor, not of Hass, that he would offer up to scrutiny. It had been him whom his predecessor had chosen to replace himself, the various items of shaving equipment ranged neatly around the crown of the basin. At first he had refused, but then was only too happy to accept. Most likely, it is because he was to shave Hass the following morning that he recalls Hass so entirely that evening – the weight of his walk, the strength of his momentum. After the day, he imagines it would have been the most he could do to pick up his feet from dragging into the dust. They would not really have spoken.

They would have felt the warmth of the dormitory when they arrived, the edges coming and going into the windows – the notion that life was a continuity of places in which one could spend time, then vacate. For no longer than would have been needed, he studied Hass’s skin – the graze of fine hair that covered it, the strange blueness underneath – and then they pulled themselves together and went in.

Not long after they got back, they would have rinsed themselves of any earthiness they had let thoughtlessly stick to them. The meal would have been served. This eaten, the lights would have been turned out, and they would have slept.

Vogel never thought to make a record of how it was he came to fall asleep each night – the motions through which he passed, the shapes through which he strained his body – a neglect which has calloused to a point of frustration. Where sleep is now easy for Vogel – he imagines it accompanying him in every moment, blushing and half-hiding its face behind the prow of a newspaper – every night in the dormitory he would need to force himself into it, as if feeling his way along the walls of a lightless passage to a single opening, behind which sleep, he supposed, existed. It seems inconceivable that something was not lost in forgetting, that recalling would not turn out to be useful in some way.

Having slept, he would have woken early and dressed acrobatically within his bunk – then would have left it to retrieve the basin, the lotion, and the razor. He would have filled the basin with hot water from the tap, which would have given him some moments to think as the steam fled the pipes. There would still, he imagines, have been flaws in his movement, bearing the basin to where Hass slept. Those stabs of hatred he must have felt when creaks in his joints broke the silence remain easily retrievable.

He would have climbed to give the signal at Hass’s bunk, the basin pinned to his left hip, keeping his right hand on the ladder before raising it into the curtain. Hass, he recalls, accepted.

Already dressed for it, Hass pulled the curtain all the way back and shuffled into place so there would be room for Vogel, who stooped to enter, wedging the basin into a corner. He closed the curtain when his hands were free. He began warming the lotion between his palms and the tips of his fingers, watching Hass start to stretch out. This he seemed deeply absorbed in. Plates of him split and shifted to level his surface which steadily brought itself closer to the flat line of the mattress. When he next looked at Hass’s face, Vogel noticed that he’d closed his eyes.

After Hass had finished, Vogel recalls the insistent pull of something, a regret that anything would ever have come to disturb him. He began spreading the lotion at the jaw. Hass stuck out his chin to give access to his neck, into which catchment he worked the lotion until he felt the collarbone below him. Vogel moved downwards in small, calm circles. He rotated his hand at the wrist to reach the farther underarm. From here to the crest of the hip, where Hass’s body faced away, it was necessary to spread the lotion blind. He spread it with even care. Where certain clefts proved unreachable, or uneven, and moraines of bone showed through, he let them be.

He rinsed his hand when he finished, and picked up the razor.

Poised over Hass, he began to cut into the foam. Even if, having done so with someone else every morning, he was used to the movements and sensations of shaving, it still excited him to see the skin, disembodied through the gap he’d made and misted over with what was left of the lotion. Where the razor brought out imperfections, moles, tags, which hadn’t been visible behind the hair, he did not pay them any attention. When he finished a section, such as a cheek or the underside of the chin, he would wipe this away with the hem of his sleeve, which would crust over if he delayed too long. Sections such as the cheeks or the central swaths of chest he would attempt to cover in long, sweeping motions, where he could feel the sensations at the end of the blade travel evenly from his hand to his shoulder. Other parts, where the body became more pedantic – on Hass, the valleys undercutting the projections of ribs – necessitated shorter, repetitive chipping motions made from the wrist, to make the razor flick into the hollows. You could not force the razor, and it was useless if you tried. At best, you could pull the skin into a more perfect surface.

Once, Vogel felt a break in the thoughtlessness as he leant. His head was suspended above Hass’s abdomen. He paused between the strokes of the razor. He no longer recalls what he thought exactly in that moment, only that it was thought, and not the flux of acceptance and experience in which he had been immersed before and subsequently. There was a moment where it threatened to bend back over itself, to crush under its own weight – but it passed. Now, he wonders how it would have been had he understood the weight. If, putting the razor once more to Hass’s body, its path had slipped, maybe, or the blade had caught somewhere or come loose, if he had bitten it in and the skin had been broken. Would Hass have stayed longer? The thought of an interruption never leaves him, as if it were the only reason he had ever shaved anyone. Hass did not move. Vogel continued shaving where he had left off.

In his memory, it is as if Hass was already edging towards that state of non-being, as if he faded beneath Vogel’s gaze. But always he remained in place, beneath Vogel and the blade, until Vogel wiped off the last smear of lotion, and disentangled himself. Then, they exchanged words, and Vogel left to get ready to go to work again.

Vogel repeats certain facts to himself at times, as the sequence of events after this becomes muddier – that this could not have been the last time he saw Hass, and that other, more partial contacts must have intervened between the shaving and the final break; then, that Hass had not disappeared into any emptiness at all, but into a clear and definite orbit of other people and locations. Where certain, recognisable scraps of him would have remained over time, others would have been cast off as they ceased being necessary. If they were to cross paths, surely they could reconstruct something from these – a closeness or an understanding.

When this occurs to Vogel, he leaves his bed and busies himself with things in his flat. He cleans his countertops and the taps of the sinks, then the taps of the bath. He pours a solution down the plugholes to make the water drain through them more efficiently. Though he is careful to accomplish each of these quietly, in case the noise intrude into other flats, each, in the silence of the building, seems to surpass the world’s capacity for sensation. After he sweeps the floor of his bedroom, he is unable to stave off sleep any longer, and will close the curtains in order to return to bed. He wonders what the arrangements of their meeting will be when he finally gets back in touch. He supposes that a degree of distance would be inevitable, though with discipline, recoverable. And, when it came to it, the wrench, would the circumstance of contact be direct or remote? ∎

Words by Harry Lauchlan. Art by Matthew Kurnia.