Keratin

At night I dreamed we lived at the bottom of a lakebed and I braided your hair. My child fingers, thin as chopsticks, weaving in and out of your mass of tangled curls. Underwater, your seaweed hair floated around your head, your pale face haloed in its soft cloud. Your closed eyes like a dead saint.

I remember learning that hair and nails are made of the same substance, keratin. This always seemed strange to me, your hard translucent shell-like nails and your slippery strands of hair. My fingers weaving fishtail braids, French braids, Dutch. Your hair clumping out in my hands like fistfuls of dust. At first I wove increasingly elaborate braids to hide the bald spots, then shaved my head in solidarity. Our hair looked like snakes sliding together down the drain, two different colors, intertwined.

When I was little I read that your hair and nails keep growing after death. Later I learned they temporarily appear longer as your skin decays. I pictured rows and rows of bodies underground, their talon-like nails scraping through the earth, hair as long as Rapunzel’s cradling their desiccated limbs. Little animals burrowing in it for nests.

We were sitting together under the apple tree when you asked if you could cut my hair. You picked up a clump, examined it, cut a jagged gash with safety scissors. I did the same to you. We watched the strands feather from our hands. At the salon, I had watched damp clippings coil like caterpillars on the wet floor; here it blew from our hands like chaff from wheat. We dug a hole with our hands and buried it together beneath the tree. I slipped a strand of yours in my pocket for luck.

Sometimes lovers would exchange locks of hair. The Victorians even created elaborate wreaths of their loved ones’ hair. After a family member’s death, they would clip locks from their heads and weave them together: blond with brown with black with red. Generations of dead cells eternally entwined. Only rarely is the hair white or grey; the sleek, shiny strands are of those who died young. Sylvia Plath’s mother kept her ash-blond childhood braids. Still with ribbons attached, they were presented in a Plexiglass display case at the National Gallery.

After you died I went looking for your hair. I pulled strands from your hairbrush and vacuumed them from our kitchen floor. Occasionally I found them balled in corners, clinging to our couch cushions, tangled in the drain of our shower. Your hair was everywhere– it turned up again and again. After weeks and months, its tangible presence remained.

Months later, when I gathered the strength to pull the sheets off your bed, I found what you had saved. Under your pillowcase, twined together like a heart, lay what I had forgotten: two locks of hair, light and dark, yours and mine. ∎

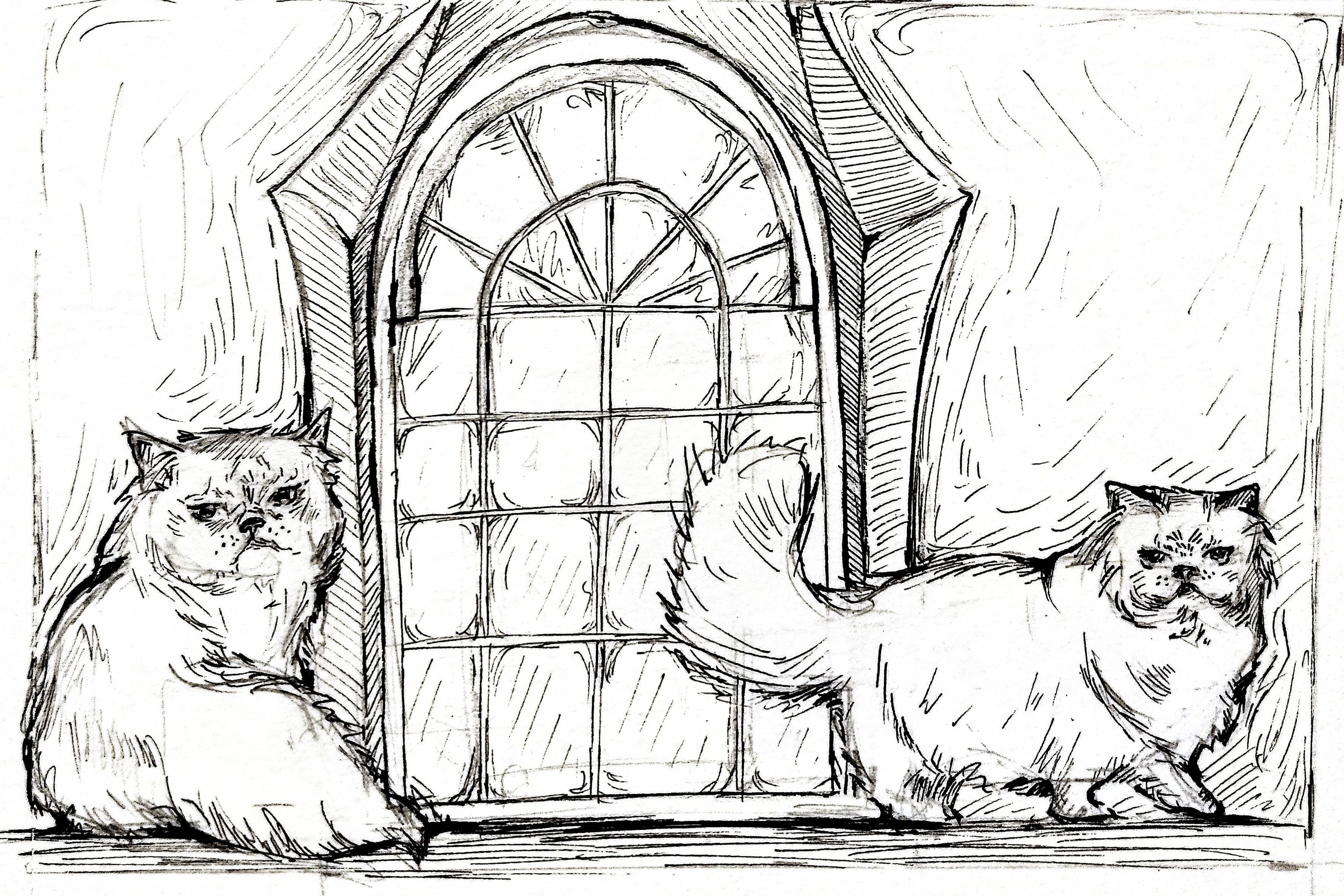

Words by Eliza Browning, winner of our HT22 500 word competition. Art by Eloise Cooke