The Scam of the Morning Routine

by Imogen Whiteley | August 21, 2020

What does a Successful Person do in the morning? The answer, it would seem, if you read enough articles about the CEOs of fashionable start-ups, is a lot: they get up at 5:45am, drink a glass of ice-cold lemon water, run a marathon, take some grateful breaths in the shower, and still find time to meditate before their work day begins.

If this all strikes you as a little American Psycho, you’re not wrong: in May 2016, Vogue published a YouTube video of Margot Robbie re-enacting Patrick Bateman’s morning routine from the film, satirising the continued ubiquity of the ‘psychotically perfect’ routine. The Successful Person’s morning routine has been a trope for about as long as the concept of ‘successful people’ has existed. Nearly two thousand years before Mark Wahlberg claimed on his Instagram to get up at 2:30am to work out twice and take the cryo-chamber for a spin, Pliny the Elder is supposed to have risen at midnight to have more time to study literature. Pliny’s daily routine, incidentally, included the ancient Roman answer to cryotherapy – a cold bath. Much like the 19th century historical theory of the Great Man, which emphasised the superior intellect and personal qualities of individual ‘heroes’, the modern Successful Person is imagined to be naturally better than the rest of us. The routines of successful people are often framed as key to their success, juxtaposed to the rest of the world. The discipline and single-mindedness needed to wake up at the crack of dawn to improve your mind and body is presented as aspirational, evidence of the exceptional personalities of CEOs and celebrities, personalities which must be the reasons for their success.

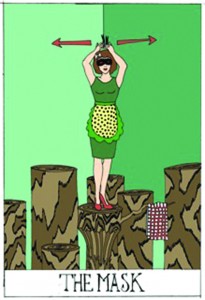

For something to be aspirational, though, it needs an audience to aspire to it; that audience is the rest of us. The morning routine creates the illusion of superhuman productivity – but there’s something performative about it, something primarily concerned with creating an illusion of productivity that seems convincing to the outside spectator as well as the Successful Person themselves. This image-conscious, matcha-latte-and-sunrise-yoga version of what it looks like to be productive creates an impossible and damaging standard for the ordinary people who skim articles about these routines. Feeling tired and burnt out from our daily lives and work, we turn the responsibility for those feelings onto ourselves, guilty that our version of getting things done doesn’t look ‘right’. This very specific, highly aestheticised version of what success looks like comes with the implication that successful people are successful because they have uniquely productive personalities. By implication, the rest of us – the world that is not yet awake while the CEO answers early-morning emails – are just not cut out for success, and won’t be until we replicate this very particular lifestyle.

That successful people’s morning routines often contain things like meditation might be good for them, but the performance of productivity often takes precedence over work itself. CEOs often self-report working long hours – Elon Musk’s 120 hour workweek being a notable example – but the ordinary reality is plainly different: a 2012 study by LSE and Harvard Business School analysed time logs kept by the personal assistants of CEOs, rather than the CEOs themselves, and found that the average workweek was more like 55 hours. Of this, 5 hours were taken up by business meals, and 20 were ‘miscellaneous’ – a category consisting of travel, exercise, and personal appointments. These are not activities that the average worker is paid for, or able to count as ‘work’. The definition of work appears to shift depending on who is doing it. Successful people are able to count self-improvement activities as part of their workweek, which most people would only count as leisure time, allowing them to report working incredibly long hours and reinforcing the idea that they are exceptionally productive. Work expands to fill the space we give it, and today, with the rise of the gig economy and the side-hustle, there is a sense that we’re expected to give our whole lives over to work.

A YouTube video about the ‘1 Billion Dollar Morning Routine’ suggests activities such as “recalling your dreams” – apparently, in your dreams you are “processing […] and working on solutions with your subconscious mind”. Unlike “most people” who “forget their dreams”, the speaker, Jim Kwik (who does not appear to be a billionaire but has built a career in part on telling people how to become one), says that successful people make sure to extract all that valuable subconscious information. This is a bizarre approach to life, suggesting even rest should be about improving your work and productivity. Other habits suggested are “making your bed”, “drinking water”, and “breathing” (while thinking about “excellence” and “oxygen”, amongst other things), and “one or two minutes of movement”. Each of these ‘habits’ is given a detailed pseudo-intellectual justification. Everyone is moving, drinking water, and breathing, but this video suggests that successful people do these things with work and productivity in mind, and that marks them out as different to the rest of us. They’re successful, the video suggests, because they allow work to become part of every aspect of their existence – including, incredibly, the suggestion of a “to-feel list” – even our emotional states are supposed to be productive. The implicit logic of these morning routines is damaging, reducing people’s value to what they are able to, or appear to, produce.

In fact, successful people do not get to where they are because they drink lemon water. The perspective which emphasises the importance of the morning routine suggests that dedicated hard work and sheer force of personality are solely responsible for success, rather than luck, connections, or inherited wealth. Although personal qualities play some part, the focus on these routines obscures the role of pre-existing privilege and the invisible army of employees who enable the successful person to prioritise their own personal development. Often, the additional productivity tasks in these optimised routines expand to fill time that other people would have to spend cleaning their own houses, for example. There is also a gendered aspect to this – men have long relied on the unpaid domestic labour of women to advance their careers – but even when this work is financially compensated it often remains invisible and underpaid. Elon Musk claims to eat his meals in less than five minutes, something which is framed in articles about his routine as a personal achievement indicating his superior productivity, and therefore social and moral value. Of course, he’s not actually better at streamlining his life than the rest of us – he just has workers to do things most of us do ourselves. Something that remains glaringly absent from the routines of most successful people is any mention of the workers who simplify their lives, allowing them to create a lifestyle of optimal productivity and ease. The presence of these employees is carefully omitted – occasionally a personal assistant or trainer is mentioned, often in a tone that suggests they are a particularly loyal friend, rather than an employee. Cleaners and cooks, however, are almost completely absent from successful people’s records of their time.

This pattern is nothing new. Even Pliny the Elder didn’t do all his own reading – one person read to him, and another took notes as he dictated. The ancient Great Man, like the modern Successful Person, is more often than not an illusion. His nephew, Pliny the Younger, described his uncle’s work habits in remarkably similar terms to the framing of the modern Successful Person’s daily schedule. Every part of Pliny’s day was organised around work – something which was only possible because of the labour of his workers: when travelling, “he kept a shorthand writer with a book and tablets, who wore mittens on his hands in winter, so that not even the sharpness of the weather should rob him of a moment”. It was not Pliny the Elder who had to suffer the effects of continuing to work in cold weather, but his inferior who actually put stylus to wax tablet. Though it was Pliny, of course, who was admired for his exceptional dedication to his work and received the credit for work heavily supported by slave labour. The Great Man theory of history suggests that exceptional individuals change the course of history through their incredible personal qualities, but Pliny the Younger’s account of his uncle’s work habits exposes the way that the work of Great Men often, if not always, relies on the unacknowledged labour of others, which is then assimilated into the achievements of the Great Man – or Successful Person – themselves.

This illusion, and our culture of work for work’s sake, has damaging effects on people who are trying to ‘make it’. A quick search on social media for the world “hustle” reveals hundreds of aggressively pessimistic maxims to this effect – someone will always hustle harder than you. Nobody cares if you’re unhappy. No one owes you anything. No one will finish your work for you. Rise and grind. No one will do it for you. The idea that the morning routine is key to success suggests that personal strength and ‘grinding’ are the only way to success, when in fact successful people are able to indulge in morning routines that are so obsessively focused on self-improvement because they are already wealthy enough not to need to spend time on other pursuits.

The effects of the coronavirus pandemic have thrown our usual ways of working and living drastically off-course, creating a moment in which it feels more possible than ever to question how our ‘normal’ way of life worked, and exactly who it worked for. The fantasy of the Successful Person’s morning routine can make us feel like we’re doing something wrong if we’re not up at the crack of dawn, or if our version of productivity is messy or wouldn’t photograph well – even if we’re actually doing the things we want to do. The disruption to routines and systems caused by the pandemic provides an opportunity to radically reimagine what work and success could look like, and to reconstruct our way of life in ways that are more progressive, less exploitative, and more human. These morning routines create a very particular picture of success, an image that is difficult to fully let go of – but we might all be happier, and even more productive, if we did.

Words by Imogen Whiteley, art by Josh Boddington.