Bruly Bouabré’s ways of seeing

by Jiaqi Kang | December 14, 2019

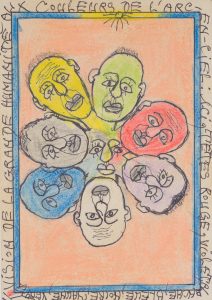

Seven disembodied heads float in a circle, cheek-to-cheek, their chins pointing to a face in the middle. They look like old men: wrinkled foreheads, receding hairlines, long, drawn-out faces, and empty eyes staring out ahead. The shapes of their eyes, noses, mouths are crude and repetitive. This might be why the Telegraph called his work “childlike”. But who is this child?

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré never received any art training. But in 1948, he underwent a prophetic vision, announcing in 1958 that he was founding a new religion, L’Ordre des Persécutés, and that his name was now Cheik Nadro. In 1989 his art career took off when he was one of the ‘primitive’ artists featured in the monumental exhibition Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which sought to compare the ethnic arts of non-Western cultures with the cutting-edge conceptual art of Europeans and Americans.

His work is collected as ‘African contemporary art’ on the global market. Yet Westerners seem to like him precisely because for them, he embodies the idea of the backwards, ignorant tribesman: scratching wildly colorful drawings in a devotional stupor. In 1995, with this in mind, the Nigerian intellectual Okwui Enwezor commented: “This is the kind of art we African writers and critics wish to disinherit.”

But Bouabré cannot be so easily stereotyped. He was an educated, multilingual government clerk who had lived through French colonial rule as well as Côte d’Ivoire’s independence in 1960, and he wrote extensively on the customs of his Bété people. He knew exactly what he was doing when he courted European intellectuals, and used their academic fascination with authentic African culture to his advantage. When he first founded his religion in 1958, he’d been helping French anthropologist Denise Paulme with her field research. He invited her to attend his proclamation – probably hoping that she would write about it (she did). That same year, Bouabré sent Théodore Monod of the IFAN, a ‘Black Africa’ research institute, a major project he had been working on: creating an iconographic alphabet for the Beté language, which had no written form. Monod eventually wrote about this too. As Bouabré grew famous for his art over the years, he streamlined his production process by having his sons prepare his cards and draw the sun-filled blue border that features in all of his pictures. He never passively waited to be ‘discovered’ by the contemporary art world, contrary to the assumptions of the collectors and curators who were fascinated by him.

A recent exhibition at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University has been the first step in a long overdue re-evaluation of Bouabré’s legacy. In a small room painted bright yellow, from 20 June 2018 to 2 March 2019, Alphabété: The World Through the Eyes of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré showed Bouabré disrupting notions of art and analysing everyday life. Dr. Amanda Maples, who organised the exhibition when she was serving as the Cantor’s Curatorial Fellow in African and Indigenous American Arts, told me that tiny spaces like the Patricia S. Rebele gallery where the show took place “really lend themselves to close looking.”

When asked why she thinks Bouabré is being reassessed at the moment, she says that there is a “push to reconsider the Magiciens de la Terre exhibition that brought so many contemporary artists of African descent to the forefront, including Bouabré, because they were presented from a particular Westernised worldview.” The exhibited images, created in the late 2000s and early 2010s, just before the artist died, not only engage with Côte d’Ivoire’s colonial history but also investigate the ambiguity of modern life. From the 1980s, neoliberal ideas and the promotion of self-interest and competitive markets led Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan to drastically reduce state participation in the economy, creating a ‘laissez-faire’ environment. As the years passed, regions of Africa that were recovering from colonisation and violence were heavily encouraged to conform to free-market economics by seemingly neutral entities like the World Trade Organisation and the World Bank. Corporations went multinational, and soon Coca-Cola logos abounded. The aging Bouabré cast a keen eye over these developments and relayed this perspective in his work.

In 2002, Bouabré told anthropologist Cédric Vincent that historically, white colonisers have dominated written discourse on Africa, silencing native voices. “I’m literate,” he said, “so when I make a drawing, I want to put down the thoughts that pertain to the work I’ve just made. The work is there, but we also need to clarify what it says, we need to have this discourse alongside it. Africa has laboured a lot, but she hasn’t been able to explain her labour. This is a fact that has to disappear.” Bouabré aimed to give a voice to the oppressed, to let the subaltern speak. He did this not only through his invention of the Bété alphabet and through his writings, but also within his artistic work.

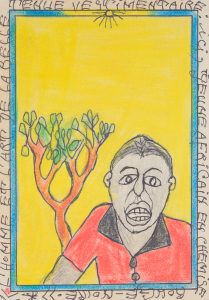

In ‘Man and the art of dressing well: here, young African in red-black button-up shirt’ (2009), the male African subject looks directly at the viewer with his mouth open in a grimace, as if protesting our gaze. The image cuts him off at the torso, subverting the dehumanising tradition of nineteenth-century ethnography, which infamously objectified naked African ‘tribesmen’ standing next to baobab trees and huts. Bouabré isn’t just reframing the way the young man is being seen, but gives him the ability to reject being seen altogether.

Anti-colonial discourse has long run parallel to nationalist and culturally essentialist ideas. In ‘Decolonising the Mind’, Ngugi wa Thiong’o famously called for a wholesale rejection of the coloniser’s language, and asked his literary peers to begin writing in their own languages. Similarly, art critic Olu Oguibe’s complaints on white fetishisation of Bouabré (whom Oguibe calls “Felix”) betrays a preoccupation with an ‘authentic African-ness’ that lies beneath all of the white man’s stereotypes.

But Bouabré asks: what is ‘indigenous knowledge’ in a former colony? Côte d’Ivoire was completely transformed under decades of French rule and both cultures became inevitably entangled. In modern times, is there really such a thing as a ‘true’ Ivorian identity without any European characteristics, and is it regressive or futile to go back into the past to try and uncover it? Bouabré instead asks how we can move forward and create a new, progressive world. He doesn’t shy away from appropriating the French language in his work – after all, French now belongs as much to him as it does to elite academics like the anthropologists Paulme and Monod. “Bouabré is an inspiring figure to consider,” Dr. Maples says, “in that he wanted to privilege the legacy of oral languages and histories by adapting it to the Western model, yet making it accessible to all people, everywhere.”

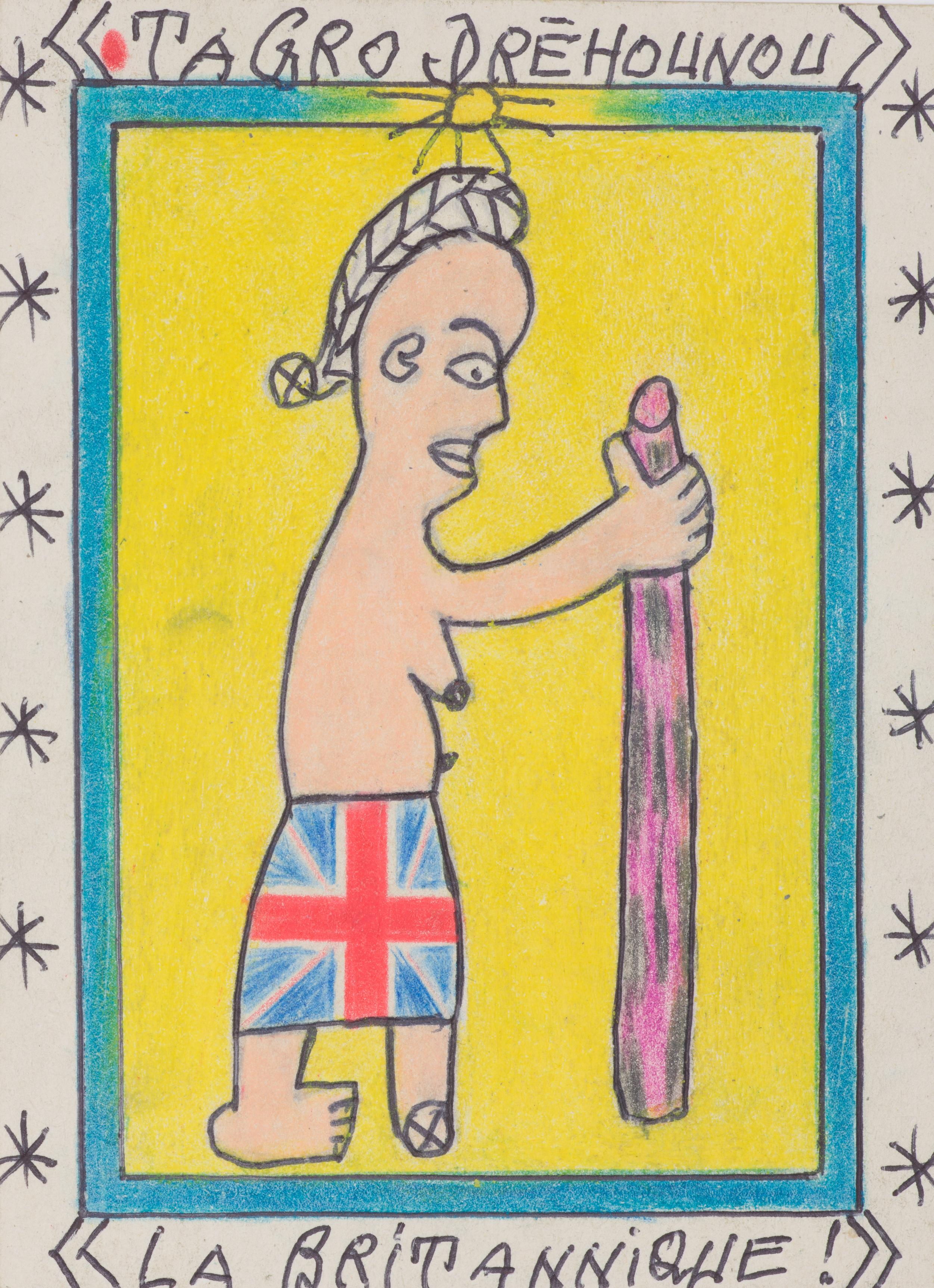

This universalism is clearly expressed in the Tagro Dréhounou! series where Bouabré depicts his mother with 4 different nationalities: Central African, British, Cameroonian, and Georgian. In each picture, she looks exactly the same except for the flag on her skirt. The arbitrariness of the colours he selects for this series – an orange background, a pink spotted stick – throw into question the colours which do, at first, seem to make sense: beige skin, black skin, the colours of a national flag. Here, colour defines meaning, Bouabré appropriates the coloniser’s invention of ‘race’ as defining one’s humanity. Yet he also shows that national identity is skin-deep too: without the national flags drawn onto the women’s skirts, how would anyone know where they’re meant to be from?

At the same time, I wonder whether we are all equal: despite their portrayed sameness, the lives of these four women would have been drastically different. How valuable are buzzwords like ‘multiculturalism’ in a world still defined by structural inequality? And what does it mean to be ‘African’ – is there a singular, unified identity for the continent that doesn’t play into colonial machinations?

Bouabré’s art doesn’t see anything as static or pre-defined, passively existing, out there waiting to be possessed. He doesn’t act like he knows everything. Instead, he seeks a process of knowing and understanding what he sees through the practice of depicting it. Bouabré told art historian Sidney Kasfir: “I do not work from my imagination. I observe, and what I see delights me. And so I want to imitate.” But Bouabré’s idea of “imitation” is far from the Western canon’s notion of it. It is not material wealth or the quality of light that he wants to capture. Instead, he revels in the human eye’s ability to narrow in on only the details that seem to matter, like a ‘divine sign’ in an orange.

“He chose syncretism over singularity even while championing our commonalities, universalising us,” Dr. Maples continues. “This is especially interesting when you think about the rhetoric of Africans being ‘othered’ or ‘primitivised’ by outside points of view, as he would have known. If we all have something in common, it levels the playing field.” She adds: “But I can’t stress enough that he was also inserting local knowledges, histories, and language and that specificity is still so crucial. It teases out questions about the articulation of global identities and ideas in local ways.”

In his series of women in the rain in Vienna, Yerevan, Jeddah, Rosario, and St. John’s, Bouabré denies us anything that might make the location of the scene unique: no iconic buildings, but just text and a curtain of rain, blocking any kind of connection the woman could have with her surroundings. A cross-cultural, hyper-connected society puts us in touch with people from around the world, but globalisation can also be homogenising: the women all look the same in their adherence to Eurocentric fashion.

Or maybe it’s just the same woman, wearing different coloured dresses, holding different coloured umbrellas, standing against a flat backdrop in a studio. Why should we take for granted what his titles say, anyway? Where most artists would just write their title, Bouabré intentionally includes quotation marks around them. Snaking around his drawings, the scribbled titles literally serve as a frame, and the quotes add a second frame. Based on Bouabré’s tendency for narratives, it’s possible they denote a narrator’s voice, presenting a story to the viewer while remaining distant. Indeed, Bouabré satirises the idea of the male artist-genius integral to the Western canon: Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Pollock. On the back of each picture, he sardonically writes “Signature-auteur:” before signing his autograph.

When tracing over his pencil outlines with ballpoint pen, he presses unbelievably hard, leaving deep grooves in the cardboard, as if he were possessed by some spontaneous, divine inspiration. Yet, comically, the pencil lines are still obvious underneath. Bouabré suggests that he never really took anything seriously, especially not his role as Cheik Nadro. He knew all about the performative nature of art, and sought to use his unique lexicon to explore it.

Bouabré dreamt of a world without borders. He did not claim objectivity, instead celebrating the mysterious and ambiguous. The world, dominated by Western white men who assumed they had the prerogative to interpret and classify everything, saw only the apparent immaturity of his style. He was depicted as an irrational, superstitious ‘savage’ whose lack of ‘civilisation’ made him charming. The reception of his work raises questions about the role art can play in politics. To what extent can you ‘subvert’ white colonial mindsets if they insist on overlooking the complexity within your work? And is it enough to just destabilise notions of identity, or should more be done to galvanise action? Bouabré brought these questions to the table. Now we must engage with them.∎

Words by Jiaqi Kang. Cover Art by Chloe Dootson-Graube. Images courtesy of the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University; Gift of Stefan Simchowitz.