Placebo

by Liv Moul | November 12, 2019

A book belonging to Alexander Smoakes was open on the table, and he was staring at a word he didn’t know.

Smoakes became angry, the seeping kind. He did not feel himself getting angry, but became it, because this was the kind of seeping anger you cannot notice in yourself at all. It bit at him, starting beneath his fingernails as he grazed over the ends with his other fingers. He did not notice his tendons clench; he did not notice the scratch he made down the side of his thumb; nor that stretching temple movement that sidles the ears inexplicably down the head, when eyebrows wax furiously and eyebrows button downwards, hairline rising. This is the forehead of emptying thought, the ante-elasticity ready to tighten into a scream.

But Alexander Smoakes did not scream; he frowned. It was an anger that so often built in him, unnoticed, of such headshaping magnitude that, really, it wanted outbursts that Smoakes’s lonely silences could not permit. He frowned, and the anger exploded as much as it could in a temporary wrinkle, the rest subsiding as it always did, in a dry swallow.

Smoakes laughed at his own obscurity. His eyes stretched, lamppost shadows creeping away from him, and he blinked three times at the word he didn’t know. He was hoping that the obscurity would bat away with his non-existent lashes as he squinted closer and closer; his head looming into the page. The meaning didn’t come. He rolled his head to the side, so that his left cheek was fully plastered onto the paper. His cheekbone ached when he pushed his face downwards. The meaning didn’t come.

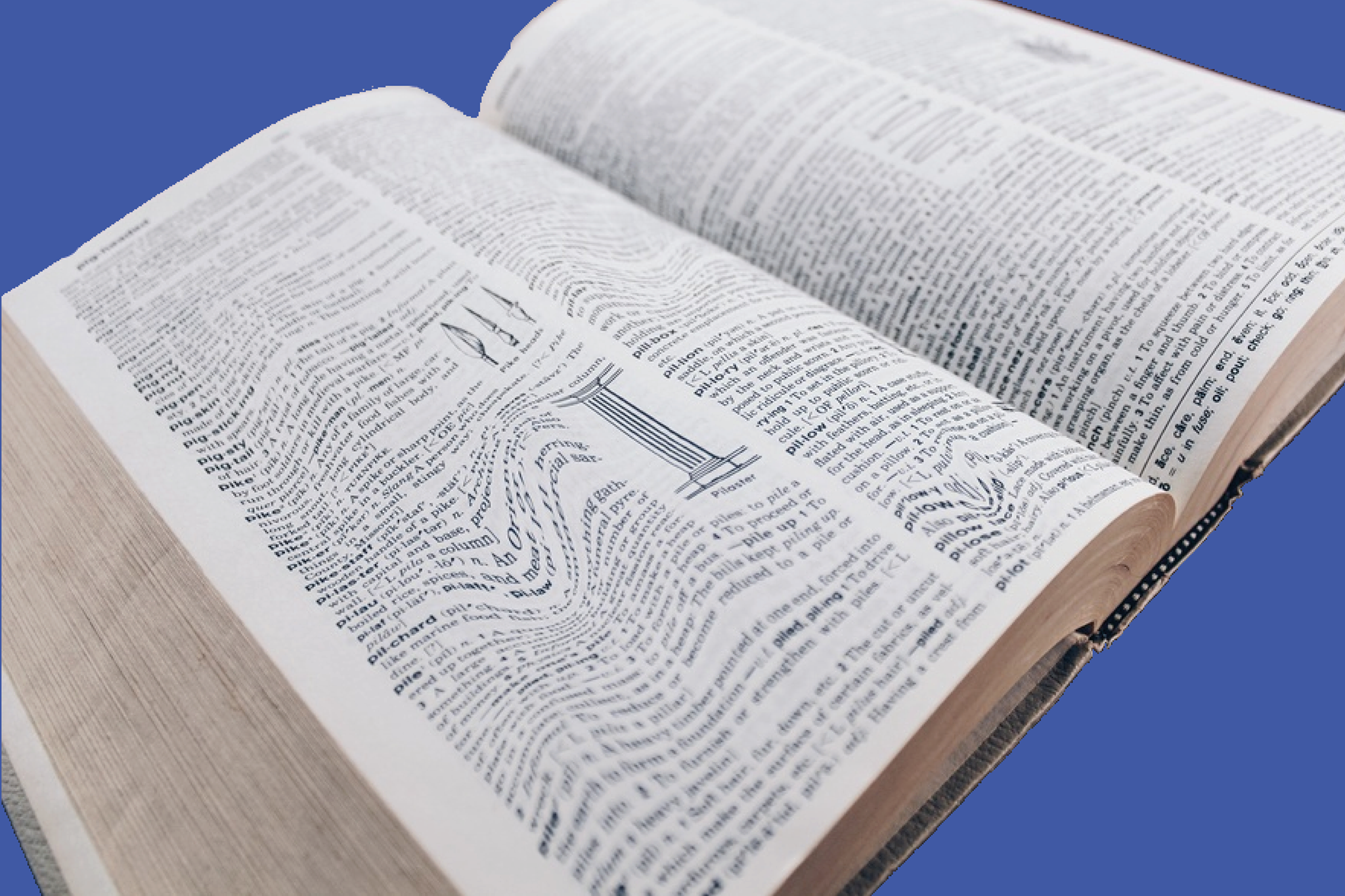

His throat scratched, surprised, as ten minutes later Smoakes had reached for the dictionary only to find that no definition of this word existed at all. He tried again. It was the most unnerving thing. The word was there, the head was there in coronet glory; emboldened, isolated, but lacking in body. The minor words, the words that should flesh out the definition, were absent. Smoakes blinked, differently from before, as this blink was inadvertent and uncalculated. A barely noticeable blink, which stood a blade of grassy nothingness compared to the obtuse, danyleonine bat-squint of before.

The telephone rang in the corner of his office, and the definition still did not exist. Not in his memory, nor in the dictionary lying open in front of him. He ignored the bleat in the corner of his ears, which was probably Delphebus Tressel and definitely magnetising the damp air. One more ripple threatened to make Smoakes sneeze. But he was focussing on the dictionary, his shelf of language in front of him.

For a sense-pilgrim like Smoakes, the dictionary was a communal construction. The headwords on the page are the walls of language, like a beam of cross-hatched wood. They are strong, running sometimes in repeating parallel grains (‘memo’, ‘memoir’, ‘memomotion, ‘memorabile’, ‘memorabilia’, ‘memorability’, ‘memorable’, ‘memorableness’, ‘memorable’, ‘memorably’, ‘memoral’, ‘memorally’ … ‘memorializer’, ‘memorializing’, ‘memorially’, ‘memoria technia’, ‘memoried’, ‘memorious’, ‘memorist’, ‘memoriter’, ‘memorizable’, ‘memorization’, ‘memorize’, ‘memorizer’, ‘memorous’, ‘memory’, ‘memory box’, ‘memoryless’).

And sometimes in isolated knots (‘placebo’).

Smoakes blinked, aware. He saw these beamy headwords on the page, and saw their screws, those tiny class indicators of a non-threatening, constructive kind: n., v., n., n., n., n., n., n., adj. and n., n., adv., adj., adv., adv., n, adj. and n., n., v., v., int. …

The smaller body of thinner writing, the definition itself, gave the shelf its plank; blank and sturdy, carpentered by some typist, but really designed by a community of speakers, writers, translators, readers. Interpreters. It was marvellous joinery. The definition could be short or long, even a wobbly application, just as long as it attached to the word.

Smoakes saw configurations of these shelves appear all over his house of English. The joinings fit together in front of him in different ways whenever he read poetry. How words are put together to make a line of verse was, for Smoakes, simply a matter of wood weight. Some senses were incredibly dense – with separate usages, multiple associations – and some were paper-thin. This had nothing to do with rarity, either. Macbeth’s incarnadine was quite surely an 80-gsm notepad shelf for Smoakes; of, however, oh! What a sequoian shelf of was.

And still, punishingly, when he went to the dictionary the wall was there, but the plank was not. It even had a teasing screw: adv. How infuriating! He couldn’t understand it. Where had the definition gone? He scanned – with bat-squint fury – the rest of the page, a pleasing soil of roots – but there, in the middle of other definition planks, was pure, blank space.

Smoakes wondered if there had been a mistake in the printing. But surely, he would have noticed – this word, quite simply, was definitionless.

Looking again at the dictionary page, Smoakes felt a familiar run of names trample through his thoughts – what would Delphebus Tressel say – what would Poppin Alabaster think – and he wanted reassurance. He turned to a word he knew there was a definition for: ‘notice’. His finger stopped scratching his thumb. It was there, the first sense, I.1: ’The act of imparting information, and related senses. (a). Intimation, information, intelligence; a piece of information, an intimation. Frequently in to give (also to have) notice. Also in extended use.’

Absorbing something he already knew meant that his mind overspilled, thick and oily. His mind overspilled, and flowed into territory it created for itself like a video-game creation opening out in front of him that he didn’t want to pursue, but he was carried along.

Notice of what? Notice of nothing. What do ‘-tice’ and ‘-thing’ have in common? ‘Tice’ is meaningless without the ‘no’ – ‘thing’ can exist without it. ‘Tice’ is a leeching suffix – ‘thing’ an independent one. The words broke up in front of him, and without him being able to help it, ‘nothing’ became two words, and ‘notice’ a dense one. In fact, the ‘t’ almost disappeared. He wondered if it would ever expand back out, if he could ever read ‘notice’ again without it being squashed as it was to him now.

God help me, he blinked.

He turned back to his definitionless word, that didn’t have its plank. What kind shelf is that? he said to himself, which he sometimes did, in his own voice more loudly than the one that leaked like that oil-spill of notice.

(At least, he pretended it was his own voice. It was a particular voice he knew he used with his friends sometimes, the voice that let him swim through these spills which, when he was on his own, he could just let happen. Sometimes he enjoyed the current, sometimes he drowned in it. But people would think him crazy if he just sat there silently, mid-flow. So the voice came out pompous, trying to make a dam for him to teeter on, to wave to the sane ones on the riverbanks and ignore the rush beneath him, underneath him, building up behind him.)

The word was still definitionless.

§

The mouth of Delphebus Tressel was unspectacular. There really is no other way to put it; he had an unspectacular mouth. And yet – it was the common thing different people remembered about him.

When Delphebus laughed, his lips spread across his teeth and all but disappeared; his whole mouth would disappear into his uncavernous cheeks, dolphin teeth on display. Nobody noticed this phenomenon, nobody knew that his lips disappeared into the space that wasn’t there in his face to reveal his dolphin teeth – but everyone said what a fabulous sense of humour Delphebus Tressel had.

When he kissed, his lips pored over their subject unclammily and in a bloom. His kiss was a rose, full, pink, and demanding notice. But nobody thought about his unspectacular mouth; they would sigh and wonder how wonderful he was – when really, he was quite average – in bed. That rose instead deserved all the credit.

When Delphebus spoke, nobody would ever have said that he had a nice voice; the opposite in fact, with his consonants filing off the ends of his words. But these shards of words, how people valued them! He would look over at Smoakes in a small pub, pursing the same unspectacular mouth over the edge of room-warmed wine. His words fell out of his grating mouth in effortless parcels, which Smoakes would gather gleefully, attentively.

“Smoakes,” he grated one evening, when the edges of his glass and his words were smudgy, “book reviews are – they’re cabinets of ideas that you’ve had about something else, maybe connected – I don’t know – Smoakes, listen to me – stop glazing. People are – listen – people are afraid that they only have one good idea and they – they squeeze it into everything. Everyone is recycling – Smoakes – it’s terrifying.”

Smoakes collected up these hollow seeds, and planted them in his own brain, hoping they would flower into something he could say later to Delphebus. It never did, and he would blame himself – not Delphebus, and definitely never that mouth.

If Delphebus were faced with a definition-less word, Smoakes thought, he would know exactly what to do with it.

§

Peering over the edge of another glass in the same swarmish pub, sat Poppin Alabaster, of whose mouth no one took any notice. Poppin was unquestionably weedy, and Smoakes despised him for it. But he loved him in a way, partly because Delphebus did, and partly because Poppin looked at you with God’s very eyes. Everybody knew it. “Good lord,” they would say, “Alabaster looks at you with God’s very eyes.”

(“He’s seen my soul,” they would sometimes add, or sometimes they would add, “Somebody buy him a drink.”)

But this wasn’t true. Poppin saw nobody’s soul, and if he did, he would have been too polite to say so. Poppin had the eyes of God because his lids closed with the same tone-changing glide as a cloud passing over the sun: the sky would momentarily darken and Poppin’s gaze disappear with the slow fierceness of death. And when he listened, his eyes waxed with God’s unclenching knowingness. It was impossible to know if he thought you were saying something brilliant, or dull.

Smoakes had to be in awe of Poppin’s absorption, but hated him just the same. With that definitionless word now glaring at him in its white blankness – the bold wall of the word sitting without its body – Smoakes tried to look at the page with God’s eyes. He looked, adrenaline cut with hate, –

It was useless. The word was perennially definitionless.

§

After a sleep of ten years, or just 30 minutes, Alexander Smoakes awoke. Ashamedly, his nose was firmly planted into the spine of the dictionary, that behemoth of rememberings, and associations; of answers, almost.

He blinked. He was Delphebus. He picked up his spidery black pen, and filled in the definition himself. There. A new creation! If anyone asked him what it meant, he could tell them, because he had invented the definition himself. He said it aloud, rosily, dolphin teeth clipping against his lips.

He blinked again, and was Poppin. He looked at the blank page and worked out a logical definition from those above and below. He had fashioned a definition from its surroundings: a bouquet unoriginal, but at least there, at least making something from existing other things.

He blinked. Alexander Smoakes looked at the still definitionless word on the page. He flipped, desperately, to the back cover of the dictionary, reached for a pair of unused scissors, and cut out a rectangle of card. Folding it over into a sheath, he pasted it over the headword and the blank space. It had no definition, Smoakes thought, the space deserved no shape. More white space defined undefinable old white space. To be erased, forgotten – and the problem went away.

It was as if the word never existed at all.

Words by: Liv Moul