Funding Under Fire

Walking out of Oxford train station, the first building you see is a sleek three-storey structure, its polished modernity incongruous with its modest surroundings. The Saïd Business School, built in 2001, oversees teaching for Oxford University students in business, management, and finance. Only the name of the school, engraved above its Park End Street entrance, hints at its connection to an infamous arms deal orchestrated decades before its construction.

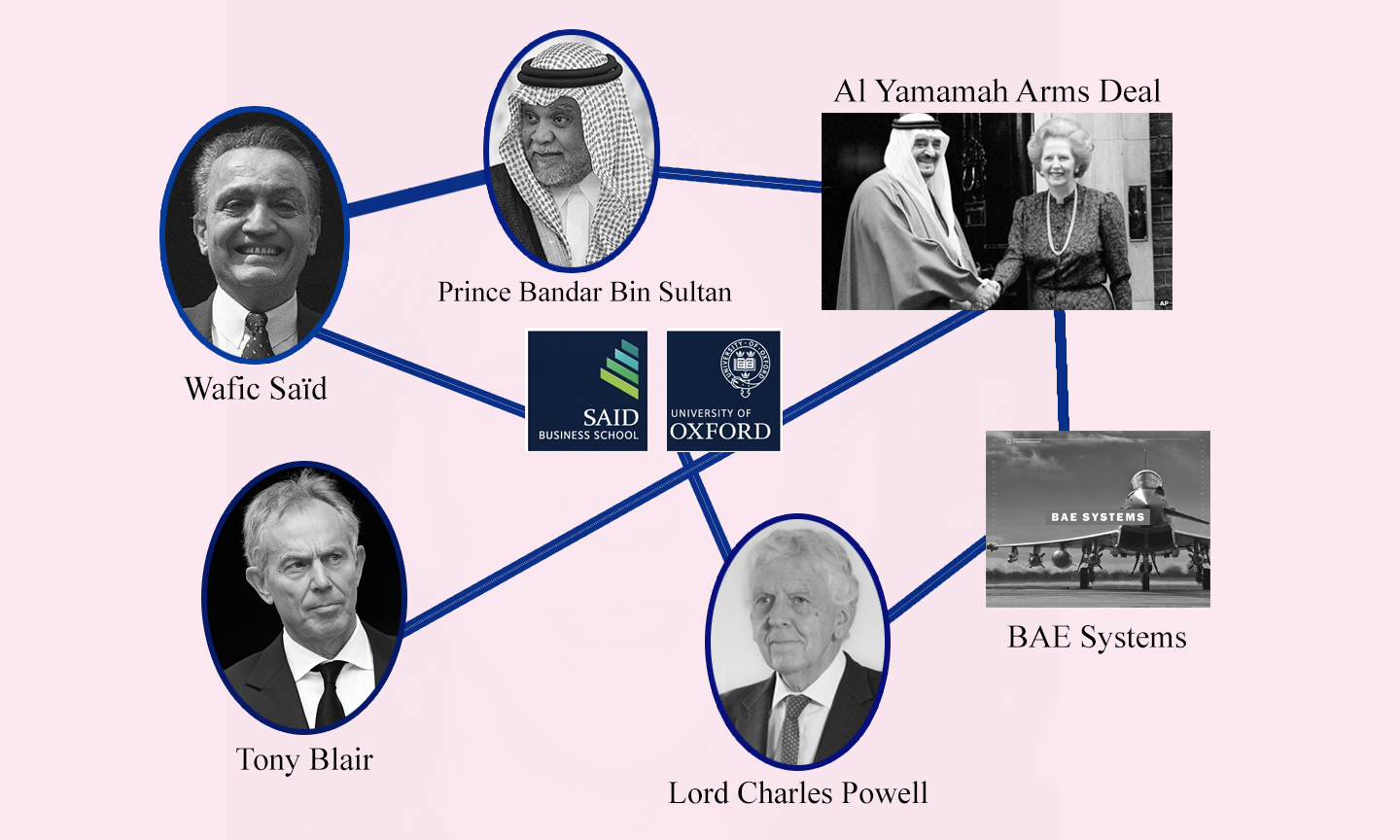

The Al Yamamah deal between the UK and Saudi Arabia remains Britain’s largest ever arms deal, earning BAE Systems, the prime contractor, at least £43bn in sales to the Gulf state between 1985 and 2007. Rumours of corruption surfaced almost immediately, but investigations were thwarted for decades. In the early 2000s, after a series of Guardian investigations, a UK government Serious Fraud Office (SFO) probe into the negotiations found evidence of ‘commission’ payments, or bribes, totalling as much as £6bn. Wafic Saïd, founder of the Saïd Business School, was alleged to be responsible for arranging a bribe of around £1bn for Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a key negotiator of the deal, and organising a £12m bribe for Margaret Thatcher’s son, Mark.

Saïd rejects the idea that he is an ‘arms dealer’, telling The Daily Telegraph in 2001, “I have never even sold a pen knife”. However, Oxford’s association with individuals involved in the arms trade has provoked widespread criticism. Andrew Feinstein, a prominent writer and campaigner around the arms trade and director of Corruption Watch UK, describes the University’s willingness to deal with figures “at the centre of the most corrupt deal in history” as “shameful and indefensible”. Along with the Saïd connection, the Oxford business school has received six-figure grants from BAE Systems, whose chairman is a visiting fellow. Moreover, Lord Charles Powell, an ex-Thatcher adviser, is Chairman of the Trustees of the Saïd Business School. In 2006, Powell was successfully employed by BAE to lobby Tony Blair to close down the SFO investigation into Al Yamamah. Blair himself allegedly used his political weight while Prime Minister to push through the school’s construction.

The connection between Al Yamamah and Oxford is loose change relative to the abundant funding from the arms industry and military agencies to Oxford University. Investigations by The Isis have found extensive financial relationships which have allowed military priorities to threaten academic freedom. These findings raise fundamental questions around the ethics of how Oxford is financed and the independence of its research.

Associated with unethical activity

Internal Oxford University guidelines state that “funding is only requested or accepted if it will not result in the University or any of its members acting illegally, improperly, or unethically”. This includes money that “originates from or is associated with unethical activity”, while all donations and research funding that “raise issues of a reputation, ethical or similar nature” are referred to the Committee to Review Donations and Research Funding.

Military contractors sponsoring research at Oxford include BAE Systems, the Airbus Group, Honeywell International, Leonardo, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Rolls Royce, and Thales. All of these organisations feature on investor exclusion lists for their involvement in the production of controversial weapons. All possess export licences to Saudi Arabia, with BAE coming under particular fire for its role in supplying, training, and maintaining the Saudi Air Force during its ongoing Yemen offensive. In September 2019, Amnesty International released a report accusing seven arms companies linked to Oxford of an “alarming indifference to the human cost of their business” in a manner that could “expose these companies and their bosses to prosecution for war crimes”. More recently, arms companies connected to Oxford have been heavily criticised in the press for their role in arming Turkey’s forces ahead of the Kurdish offensive.

In September 2019, Amnesty International released a report accusing seven arms companies linked to Oxford of an “alarming indifference to the human cost of their business”

Their involvement in dubious overseas activities is not the only criticism to be levelled at these companies. Besides its violent implications, studies suggest that the arms trade accounts for as much as 40% of all corruption in world trade. Rolls Royce, which has given Oxford over £6m in the last three years alone, was forced to pay £671m in penalties in 2017 relating to claims of bribery. Thales are currently facing trial on corruption charges alongside South Africa’s disgraced former President, Jacob Zuma. BAE Systems have been accused of handing out billions of pounds in bribes to win contracts. The list goes on.

Responding to The Isis’ findings, the Campaign Against The Arms Trade’s universities coordinator stated, “universities are public institutions that are supposed to work for the public good and encourage innovation, creativity and fruitful dialogue. Instead, universities like Oxford are profiting from death, destruction, and oppression, home and abroad.”

A University spokesperson rejected these accusations, arguing that projects financed by these companies “advance general scientific understanding, with subsequent civilian applications including climate change monitoring, earthquake detection, energy efficiency and humanitarian relief, as well as potential application by the defence sector.” However, the humanitarian applications for a significant number of such projects are unclear. Individual projects uncovered by The Isis include a £129,000 grant from Rolls Royce for an Engineering project entitled ‘Tempest’, running from 1 December 2018 to 29 February 2020. Although no details of this project have been made publicly available, Tempest is the name given to a Rolls Royce, BAE Systems, MBDA, Leonardo, and MoD programme to build a sixth generation stealth fighter jet. The University did not respond when asked to comment directly on this subject.

Clear-cut individual cases such as these are not the only examples of arms involvement in financing research at Oxford. In most cases, defence-related funding takes root at an institutional level. Centres for Doctoral Training (CDTs) manage research council-funded PhDs. These centres aim to provide students with “technical and transferable skills” through research and training, with an emphasis on collaboration with industrial partners. This collaboration produces sets of funded projects for PhD students, who have complained that limited choice makes it difficult for them to refuse projects. Leading arms manufacturers such as Thales and Leonardo are industrial partners at a number of CDTs, meaning their representatives directly supervise PhD projects. In these cases, when CDT projects involve confidential information, students may not be given full details before beginning research. Once students do begin research projects, it can be difficult to withdraw, not least since project contracts often feature Non-Disclosure Agreements. One graduate student who wished to remain anonymous remarked that it is possible to be “forced into certain directions” once research has begun. PhD students also suffer if their research cannot legally be published because of confidentiality agreements, their academic freedom threatened by the priorities of the University’s military funders.

One graduate student who wished to remain anonymous remarked that it is possible to be “forced into certain directions” once research has begun.

Deep immersion

As Dr Peter Burt, a researcher for Drone Wars UK, explains, universities “provide the kind of academic expertise and knowledge, bases for research, and facilities that are not available elsewhere”. Beyond influencing academic research, financial support allows military bodies to directly access these resources.

The Oxford Robotics Institute (ORI), a subsidiary of the Engineering Department, offers an ‘Industrial Membership’ programme to prospective commercial funders. According to the Institute, membership “buys deep immersion within the ORI to the full portfolio of our research and activity”. The programme is tiered, with a “full Industrial Member” able to embed an employee within the institution with “full access” to “all of our data, software, hardware and computing facilities”. Three of the ORI’s six current industrial members have ties to the arms trade or defence agencies. One of them is a subsidiary of the sixth largest defence contractor in the world, and works exclusively on building unmanned surface vehicles. Their website lists the military and security applications of their vehicles, described as “the future for Maritime Operations”.

Oxford also houses two Rolls Royce University Technology Centres. At the Solid Mechanics Engineering department, home to one of them, three of the department’s twelve professors do consultancy work for Rolls Royce. Another professor is on the MoD’s Defence Scientific Advisory Committee’s register of security-cleared scientific advisors. Over half of the department’s research projects listed online have received funding from defence-related bodies, including the US Air Force. Given the power of faculty boards, especially over academics early in their contracts, it can be very difficult to ask questions about established senior professors and their connections with defence bodies. For Dr Stuart Parkinson of Scientists for Global Responsibility, the result of such connections is a “labyrinth that builds up and becomes very solidified and powerful within that environment”.

Given the power of faculty boards, especially over academics early in their contracts, it can be very difficult to ask questions about established senior professors and their connections with defence bodies.

Battle-winning impacts

The convergence between defence bodies and the University relates to both funding and personnel. Academics routinely involved in defence-funded projects have been found on the payrolls of bodies such as BAE Systems, Rolls Royce, and the MoD, working as consultants to supplement their University income. The MoD in particular has a significant Oxford crossover, with officials invited to give lectures at the University, and government defence laboratories running interactive workshops for students.

Government policy documents reveal targeted funding from the MoD with the explicit goal of shifting the research agenda towards military interests. Following its 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review, the MoD announced an initiative to “unearth defence and security pioneers” by funding programmes designed to encourage collaboration between academia and arms companies. Specific research areas where the MoD sees the “greatest potential to transform military capabilities to achieve battle-winning impacts” are outlined in the Science and Technology Framework, published in September 2019. Responsibility for delivering this strategy falls on the MoD’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Professor Dame Angela McLean – the Professor of Mathematical Biology at Oxford’s Department of Zoology.

MoD funding at Oxford University totals over £6 million for research contracts active in the last three financial years. This includes six-figure grants for research projects with specified applications including electronic warfare and drones. Oxford’s Networked Quantum Information Technologies hub, established by an MoD-led government programme, has received £61 million in grants paired with military contractors since its foundation in 2014. It also receives additional funding from government bodies including the Atomic Weapons Establishment. As of 2016, the University had overseen seven MoD-funded PhDs as part of this programme, more than any other participating university in the country.

MoD funding at Oxford University totals over £6 million for research contracts active in the last three financial years.

In addition to direct funding, the MoD collaborates with government councils to finance projects and encourage military sector collaboration. Oxford’s research council grants active in 2019 include over £80 million paired with the MoD, while nearly 40% of its £420 million of science council grants are paired with military-related bodies.

Another central facet of the MoD’s Science and Technology Framework is autonomous technologies. In November 2018, Drone Wars UK published Off The Leash, a report into the development of autonomous lethal weapons systems. Such systems – dubbed ‘killer robots’ by campaigners – are a contentious area, labelled by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as “politically unacceptable and morally repugnant” ahead of a UN summit earlier this year. In its report, Off the Leash found “tangible evidence” that the MoD, military contractors, and universities are “actively engaged in research and the development of technology which would enable weaponised drones to undertake autonomous missions.” These developments can be traced to Oxford, where The Isis has found extensive collaboration between government agencies and military contractors in areas relevant to drones. Currently funding at the University from defence-partnered grants related to autonomy totals at least £22 million, with Thales, QinetiQ, and BAE Systems – leading developers of drone technologies – providing significant financial support. Meanwhile, MoD-funded Oxford projects include a number of PhDs relating to unmanned flight control and sensor development.

These developments can be traced to Oxford, where The Isis has found extensive collaboration between government agencies and military contractors in areas relevant to drones.

A changing field

The UK universities system is at a critical junction. A long-term decline in higher education government support, combined with the impending loss of EU grants, has left university administrators scrabbling for funding. Responding to The Isis’ findings, the University spokesperson maintained that “all research funders must first pass ethical scrutiny and be approved by a robust, independent system, which takes legal, ethical, and reputational issues into consideration”. However, the pressure to find alternative financial sources has already raised serious questions about the suitability of Oxford’s current ethical frameworks. As Andrew Feinstein argues, “funding from defence companies is not undertaken philanthropically”. Just this year, it emerged that three years of negotiations and an internal ethical review into a £150 million donation from Stephen Schwarzman were subject to Non-Disclosure Agreements, sparking concerns amongst university campaigners about the University’s clear lack of transparency.

Funding from defence companies is not undertaken philanthropically.

A month on from the announcement of Schwarzman’s donation, Vice-Chancellor Louise Richardson lamented the disparity in fundraising between the University and “our American competitors”. If anything, this changing environment is moving Oxford closer to American funding models, with industrial research funding growing at over twice the rate of research grants over the past five years.

Oxford’s spokesperson concluded that the University’s research is “academically driven, with the ultimate aim of enhancing openly available scholarship and knowledge.” Questions persist about this assessment – the Campaign Against The Arms Trade’s universities coordinator stated that the findings demonstrated a “destructive role in suppressing students’ ability to contribute positively to society rather than to develop technologies of war”. The influence of industrial partners on the publication of research projects with commercially sensitive findings also hinders the pursuit of openly available knowledge. Meanwhile, although scholarship at Oxford remains “academically driven”, the considerations that determine which projects receive funding from government bodies such as the MoD are not. Further work is needed to uncover the full extent of the close connection between Oxford University and military organisations. For now, the question remains: how long can the University maintain a global reputation for progress while wedded to the military sector? ∎

Words by Ben Jacob ([email protected]). Artwork by Ng Wei Kai.