Empire Adrift

by Dan O'Driscoll | May 15, 2018

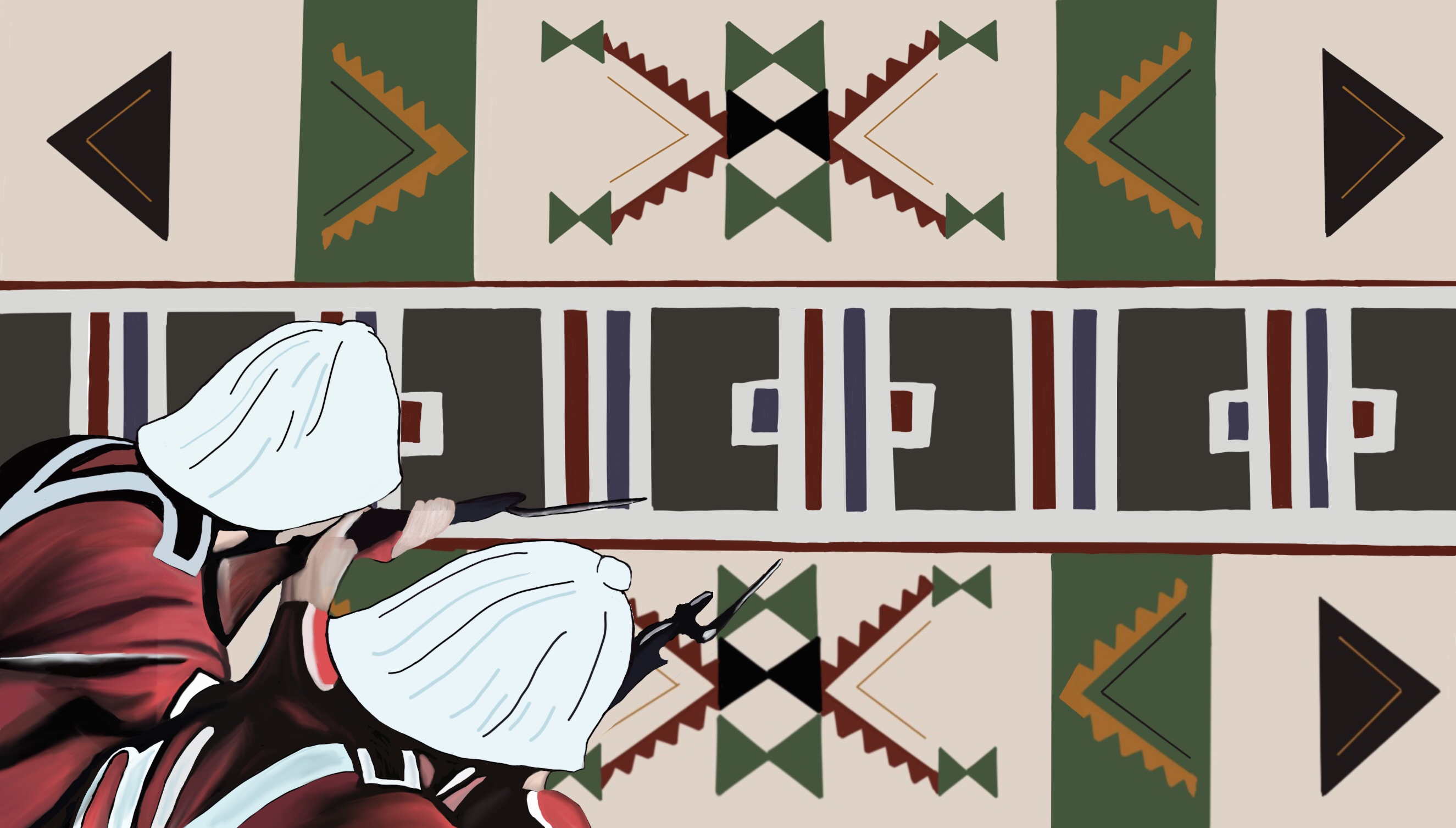

Ten years ago, I saw one of the most memorable sights of my entire childhood. I remember a column of bright red coming slowly into view round a bend in the road, progressing methodically to the beat of a drum. Cream pith helmets, golden sword hilts and medals gleamed in the sun. At the head of the column was the Royal Welsh’s regimental mascot, a white Kashmiri goat called Shenkin. His coat bore a red dragon and the motto Gwell angau na Chywilydd – Death rather than Dishonour. The boys and girls who lined the streets of the former mining town of Blaina that day must have been overawed. I, for one, know I was.

I was particularly captivated by the soldiers themselves. The only previous knowledge I’d had of real-life soldiers had been obtained via footage of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that I’d glimpsed on the TV before my parents switched channels. I didn’t realise until much later that many of the men in the bright column that day had probably served in one of these wars. Later on, these men spoke warmly to us children and even let us pet their goat. One of them asked if any of us intended to join the army when we grew up. I didn’t reply, more out of shyness than genuine indecision. In time, the question came to strike me as a loaded one. With the benefit of hindsight, the idea of scouting out future recruits for modern middle-eastern bloodbaths in a deprived Welsh town at a parade commemorating the working-class men killed in the service of their country seems both decidedly uncomfortable and grimly ironic. Nonetheless, the question itself was, at least in my case, somewhat pertinent. The Royal Welsh were marching that day to commemorate the British victory at Rorke’s Drift over the Zulu Kingdom in 1879. Specifically, they were there to honour my great-great-grandfather, Private William Henry Partridge, who had fought in it.

At Rorke’s Drift, 150 soldiers, a significant number of them Welsh, fought off an assault by over 3000 Zulu warriors. The encounter was unimportant in the greater scheme of things but it was instantly mythologised by the press and subsequently immortalised in the 1964 film Zulu. I watched Zulu, a staple of my grandad’s VHS collection, a number of times after the parade. As an oddly-fascinated ten-year-old, it was the only real source of information I had about the conflict, and indeed, the British Empire in general. The formative role played by dated pieces of popular culture may not seem a terribly positive influence on my understanding of Britain’s imperial past and my own connection to it. Indeed, in all likelihood, they probably weren’t. Nevertheless, I was impressed by how relatively progressive and relatively accurate much of the film was when I re-watched it recently.

A number of critics have problematized Zulu’s content. One 1964 New York Times review went so far as to call it “robustly Kiplingesque.” Historians like Ian Knight have insightfully highlighted the fictitious nature of many key elements, from the uniquely Welsh character of the 24th Foot to the iconic battle-field singing. Knight also noted that several scenes fly in the face of historical fact, such as that in which King Cetshwayo orders his impis to attack the British in Natal after crushing their invasion force at Isandlwana, which fly in the face of historical fact. In reality, the battle ended not with a mutually respectful parting of the ways, but with the distinctly unchivalrous bayoneting of wounded Zulus on the battlefield. These issues can be seen as part of a broader, even systemic, disjuncture between the way Britons conceive the imperial past and the way it is routinely portrayed.

At first glance, then, Zulu seems to fit into the jingoistic tradition of exotic frontier films. However, it is actually remarkably nuanced in its treatment of both Zulu and Briton alike. The British are acutely divided by class and nationality. Sir Michael Caine’s aristocratic Lieutenant Bromhead initially scorns his working class subordinates. Notions of a unifying ‘British’ identity are undermined when one of the several Welsh Private Joneses remarks to a Boer NCC Corporal that “Tis a Welsh regiment, man! Though there are some foreigners from England in it, mind.” Private Cole’s desperate pre-battle plea, “Why is it us? Why us?” punctures any suggestion that the defenders adhere to the dictum ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ while the recurrent wanton violence throughout underscores the brutal futility of the war at large. The Zulus, meanwhile, are consistently praised by their adversaries, with ignorant racist remarks by British “rednecks” swiftly put down. When the Zulus are dismissed as a “bunch of savages” or native levies as “cowardly blacks,” for example, these remarks are swiftly debunked, and the sacrifice, bravery and military prowess of black characters is highlighted in response.

Even Zulu’s ahistorical conclusion serves to depict a genuine historical shift in attitudes on the part of the British. As art historian Catherine Anderson’s 2008 article Red Coats and Black Shields highlighted, Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift marked critical turning points in the representation of black people in Victorian culture. The film itself also marked something of a new departure in the treatment of local extras. Contrary to rumours, all of the genuine Zulu extras, numbering over a thousand, were paid in full, despite discriminatory wage laws in force at the time, with many taught from scratch how to act and introduced to motion pictures for the first time during production. Meanwhile, the future anti-apartheid figurehead and founder of the Inkatha Freedom Party, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, served as an advisor on the film and even starred as his actual great-grandfather King Cetshwayo kaMpande. Given that modern historical epics (and films in general) set outside the West have struggled to accurately reflect the ethnic realities of their subject matters, this ‘problematic’ 1964 throwback may actually offer some important lessons.

For all its issues, its historical missteps, its vainglorious Anglicana and its melodramatic male voice choir-contests, Zulu probably still kept me better informed than many of the adults casually observing the parade that day in 2008. Chances are that their historical education barely touched on any of Britain’s imperial past, let alone a fairly obscure, year-long colonial struggle in South Africa like the Anglo-Zulu War. Red-coats, bearskin hats outside Buckingham Palace and Rule Britannia are among the few encounters that ordinary Britons ever have with an Empire that once subjugated a fifth of the world’s population. This lack of understanding of our past obscures the dark realities underlying much of the individual heroism that is so often celebrated. I was proud of my relative’s bravery and, indeed, still am. But I am not proud of him because he killed spear-wielding tribesmen defending their homeland with a high-power rifle. What I really admire is the ordinary sacrifice and day-to-day perseverance of the soldiers who fought at Rorke’s Drift. Private William Henry Partridge was a hard-working miner who was drafted into a conflict for land and diamonds on the other side of the world in which he had no stake. He not only fought but had to live with the consequences, among them a chronic condition that would plague him for the rest of his life. The agents of empire could just as easily become its victims.

Next year will mark the 140th anniversary of Rorke’s Drift, and, with the events of the past decade, it seems unlikely that it will be an uncontroversial date. In light of Rhodes Must Fall, controversies over American Civil War memorials, and protests by SOAS students at the glorification of Churchill at a London café, it is difficult to imagine a parade like the one I attended in Blaina occurring without incident in a student city like Oxford today. Perhaps this is a good thing. Certainly if people are – understandably – uncomfortable with a war with decidedly racist overtones being remembered in a way that glorifies rather than accurately reflects the past, then they have every right to make their voices heard. If nothing else, the inevitable debate will draw attention to this chronically overlooked period. Indeed, a part of me wishes that I myself had been precocious enough to bluntly answer “No” to that friendly soldier back in 2008 when he asked if we wanted to “follow in the footsteps” of those that fought in the Anglo-Zulu War. All too often the iconography and language of empire is used to further decidedly modern, often cynical, ends and I firmly agree that the commemoration of individuals and events should not allow the complex and unsettling truths of the past which they populated to be concealed. Yet, equally, blind opposition to efforts to connect Brits to their past will not lead to productive engagement with the harsh facts of Empire. Remembering the battle does not entail condoning the war. The opening line of WW1 poet Wilfred Owen’s haunting Anthem for Doomed Youth, “What passing bells for these who die as cattle?”, apply to the ordinary British soldiers who fought in Britain’s bloody imperial wars, and were left behind by the state thereafter, just as much as those who died at the Somme. Better these imperialist skeletons be dug out of Britain’s proverbial closet, exposed and contextualised, than left adrift in a sea of sentimentality and flag-waving nostalgia.

Artwork by: Julia Manstead