India, unafraid.

by Jeevan Ravindran | April 5, 2018

tw: mentions of sexual assault, violence, rape

16th December 2012 – a day that started like any other, but which now marks a turning point in the struggle for women’s rights in India. In South Delhi, 23 year-old physiotherapy intern Jyoti Singh climbed aboard a bus with her male friend. They had just been to see a movie, and were heading towards Dwarka, in South West Delhi. But the bus didn’t actually take them anywhere. Instead, the driver, along with five other men, assaulted both of them with iron bars before proceeding to take it in turns to rape Jyoti, reportedly for close to an hour. Finally, they threw both out of the moving bus. Jyoti’s injuries were so severe that she was flown to Singapore for treatment. Unfortunately, on 29 December, she died, becoming an emblem of the ways in which Indian society fails its women.

This wasn’t the first such occurrence in India, but it was the first to cause outrage on this kind of scale, with widespread silent protests and vigils across India, and worldwide media attention. It brought these men’s atrocities under global scrutiny. Initially, Jyoti was unnamed in the media, and was referred to instead as ‘Nirbhaya,’ meaning ‘Fearless’. In 2015, her name was finally revealed. She became a symbol of what women’s rights activists were fighting for – the freedom to live without fear.

Yet such incidents of rape and sexual assault seem bizarre when we consider that in India, women are worshipped as goddesses. During the holy festival of Navaratri, dedicated entirely to Durga, Lakshmi and Saraswati, the goddesses of strength, wealth and knowledge respectively, little girls are dressed up and venerated as the Divine Mother during festivities which last for nine days and take over whole cities. But how can this be happening whilst women are simultaneously made to feel uncomfortable in public places? It’s complicated, to say the least.

Technically, women are legally free to do what they want, a freedom which began with Indian women receiving the right to vote in national elections in 1950, after the country gained independence from the British Empire. But in many rural regions, a woman’s place is still considered to be in the kitchen, and her existence centres on providing a stable domestic environment while her husband sustains the household. In short, boys are raised to pursue their dreams and girls are raised to pursue a wedding ring. Urban India has moved far ahead in recent years, and many young women now have access to education and manage to pursue their own goals, even entering traditionally male-dominated professions such as scientific careers or driving auto-rickshaws.

Yet despite this outward culture of equality, a deep-rooted ideology of male supremacy still persists amongst all generations. The 1976 Equal Remuneration Act was a huge step forward in legislation, but a 2013 study found the gender pay gap as present as ever, with women at best earning 9% less than men, and 52% less at the opposite end of the scale. 2007 saw the election of Pratibha Patil as India’s first female president, yet under her tenure a census revealed gender population discrepancies that could only be the result of an increase in female foeticide. The customs that teach Indians to be proud of the male child and, at most, indifferent to the female, haven’t died out. For example, when a baby boy is born, laddoo sweets are given out. A girl’s birth, however, is marked with the cheaper and smaller barfis.

The difficulty lies in the fact that in many respects women are still seen as commodities who exist for the benefit of men. This perception is not only reflected but encouraged in popular culture. Female actors are often given smaller roles than their male counterparts, or appear in movies only to provide the ‘glamour quotient’. Women often grace the screen only for a few minutes, in an ‘item number’ in which they mouth enticing lyrics in order to arouse an onscreen male spectator. Film reviews contain lines such as ‘she has minimal dialogues but surely charms us away with her smile’ and ‘they heat up the atmosphere with their hot numbers’ in reference to a female actress, whilst male actors are conversely praised for their ability to ‘overshadow everyone else on screen’.

The disparity only increases with age; award-winning actresses tend to step out of the limelight as they become older, due to a dearth of well-written parts, whilst their male contemporaries continue to play the hero and romance younger actresses. Hema Malini, one of the most popular stars of the 1970s and 80s, compared herself to Meryl Streep in order to highlight the disparity between Hollywood and Bollywood in this regard, commenting that she is not offered any good roles. The Indian censor board finds fault with films for being too sexual, such as the 2016 ‘Lipstick Under My Burkha’ which was criticised for being ‘lady-oriented’. Yet it fails to comment on the perpetration of misogynistic ideologies in films such as the 2010 ‘Dabaang’, in which the harassment of the female protagonist is glorified and turned into a source of amusement.

The presentation of Indian women in film is almost laughingly juxtaposed by the fact that in reality, women in India are often criticised for ‘provoking rape’; by wearing provocative clothing, for example, or by travelling unaccompanied. The sexualisation of women in film is presented as a scandalised treat where viewers are in equal parts interested in, and appalled by, their sensuality. Solo female tourists are warned of the dangers they may face as a result. When I myself travelled alone in India, I spoke to parents who assured me that they would not let their daughters do what I was doing. I encountered a hotel receptionist who thought it acceptable to invite himself into my room, tell me to close the door and try to flirt with me, pressuring me to add him on WhatsApp. On the same day, a shopkeeper in a clothes shop asked me if I had a boyfriend, whether I was free that night, and pressured me to take his phone number. The simple tasks of checking into a hotel and buying clothes became obstacle courses.

These experiences are nothing compared to the everyday, unwilling compromises many Indian women must make in the way that they live their lives, such as not going out late at night, not glancing at men unnecessarily, not speaking in such a way that could be interpreted as flirting. The difficulty seems to be that some see women as walking opportunities for rape, and think that the duty to prevent it lies with them, rather than an attacker. Marital rape isn’t even considered an attack, and remains legal in India to this day. Women are seen as weaker beings who must submit to the male gaze, and yet are simultaneously held responsible for the actions of men.

This is hugely ironic, given the culture of worshipping goddesses. The Goddess Durga is seen to be the embodiment of strength, and is depicted as a tiger-riding, weapon-wielding firebrand. She is the equal to her husband Shiva, the lord of destruction, and together they are ‘Shiva and Shakti’, neither able to exist without the other. Yet this pairing is not reflected in wider society; the same men who might worship Durga as their family deity see no contradiction in perpetrating violence against women.

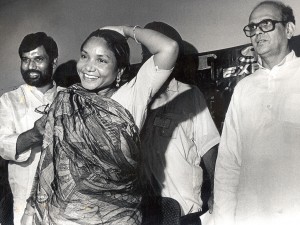

It falls to women to defend themselves and other women. The Gulabi Gang, a group of activists based in Uttar Pradesh, epitomises this reality. Their founder Sampat Pal Devi created the group in response to the police ignoring an incident of domestic violence. When 17 year-old Sheelu Nishad, a rape victim who’d tried to file a police report, was arrested on false charges of theft, it was the Gulabi Gang who organised two large protests and brought her case to justice.

Nirbhaya, the state of fearlessness, can’t really be felt in India yet. Jyoti’s rape was the only such incident in 2012 which led to a conviction in Delhi, and it was just the tip of the iceberg. However, the wave of international outcry that followed Jyoti’s rape did succeed in urging the government to tighten laws around sexual assault, expanding the definition of rape and increasing the severity of convictions. There was also a huge increase in the number of women coming forward with cases of sexual assault, which suggests a slight erosion of rape stigma.

Ultimately, there is still a staggeringly long way to go. Things are slowly but surely changing in popular culture, where a crop of female actors are portraying strong women on screen and paving the way for change. But this needs to become commonplace, and misogynistic ideologies in films must be curbed. Legislation needs to move forward, and the legal system that continue to disadvantage women through loopholes such as marital rape urgently needs to be rethought. An India in which women do not have to be afraid and are less limited by the male gaze would be one of limitless potential. India must use the momentum created by these gradual shifts in culture to push them further, so that women are recognised in all aspects as the equals of men.

If these changes can be implemented, Nirbhaya just might be within reach.

Artwork by: Sai Parepalli