The Battle of Grosvenor Square

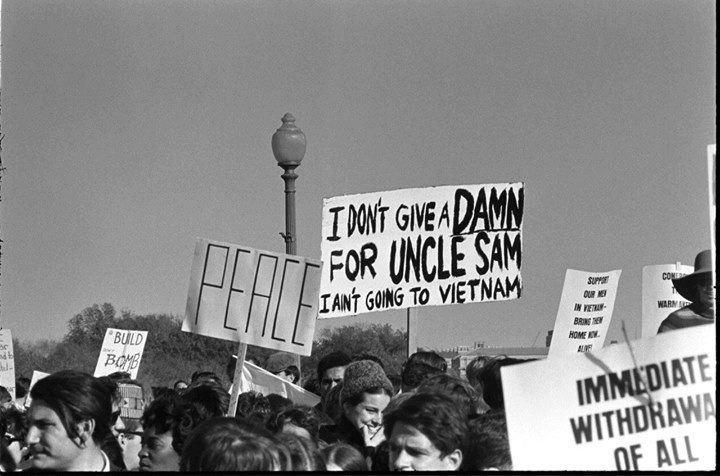

On the 17th March 1968, over 80,000 people gathered on Trafalgar Square to protest against the Vietnam war. The Tet offensive had just ended and, unknown to those at the demonstration, the My Lai massacre had occurred the day before. Harold Wilson’s government had managed to keep Britain out of the war but there was a great deal of anger at its failure to denounce the US invasion. The march, organised by the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC), was intended to put pressure on Wilson and on the US government. There was also a radical, left-wing under-current: the VSC’s leadership included Tariq Ali, Pat Jordan and several other Trotskyists.

After listening to rousing speeches by Vanessa Redgrave and Tariq Ali, the crowd left Trafalgar Square along Charing Cross Road. The organisers of the event had carefully planned the route. The march was to proceed down Oxford Street to North Audley Street via Holles Street, Wigmore Street and Orchard Street. The eventual destination was Grosvenor Square, the location of the American embassy. But the intention was to avoid the actual embassy and exit the square by Upper Grosvenor Street. Police cordons had been put in place to funnel the protesters away from the embassy and ensure that they adhered to the agreed route.

Events did not unfold as the organisers, or the police, wanted. Nobody announced the route that was to be taken at the rally on Trafalgar Square. Instead, the protesters simply followed Vanessa Redgrave, who intended to hand in a petition at the US embassy. Most of the crowd entered the square from the wrong side and were faced with a tight police bottleneck. At the same time, a small group of Maoists decided to target the embassy itself, leading to clashes with the police. Faced with what seemed to be a dangerously explosive situation, mounted detachments of police attempted to break up the crowd. The result was a series of running battles between the police and protesters that left 86 injured. Tariq Ali described the scene in his book Street Fighting Years:

A hippy who tried to offer a mounted policeman a bunch of flowers was truncheoned to the ground. Marbles were thrown at the horses and a few policemen fell to the ground, but none were surrounded and beaten up. The fighting continued for almost two hours.

Several other accounts also bear witness to police violence. In a letter to The Times, John Scarlett, later head of MI6, condemned ‘the behaviour of the mounted police as the square was being cleared.’ He noted that:

I twice saw policemen charge quite strongly at very few demonstrators who were doing absolutely nothing and both times people were heavily clubbed over the head, while one of my friends saw a girl being viciously clubbed for no reason at all.

But the police, though heavy-handed, were not particularly brutal by international standards. A letter from Jane P. Futcher, published opposite Scarlett’s, noted that ‘in comparison with American police standards, the behaviour of the English police was pleasant and agreeable.’ Unlike the 1970 protests at Kent State university in the US, no demonstrators were killed. It is telling that the remaining protesters sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’ with the police at the end of the day.

In retrospect, the protest seems like something of a dead end. It was an event, a headline, but little more. There was no change of policy on the part of the British or US governments, nor was there any shift in attitudes among the public. It is unclear what the organisers of the protest hoped to achieve in the first place. The war was already unpopular in Britain and Wilson’s assistance to the Americans was minimal. Christopher Hitchens, writing in his memoir Hitch-22, notes that he regarded the protest as an act of solidarity with the Vietnamese people. He wrote that:

Michael Rosen had written a haunting poem, published in the university’s literary magazine Isis, that hymned a then-famous poster of a Vietnamese woman in a paddy field, with a gun slung over her shoulder. Please let it be, the poem had urged, that some of the news and pictures of our revolt will reach you and put a smile on your face.

It is unlikely that the woman ever heard about the events on Grosvenor Square, and even less likely that she would have cared about them if she had. The suggestion that ordinary Vietnamese citizens would – or should – have known or cared about events in a far-off, foreign capital is faintly ludicrous and smacks of self-deception. Hitchens himself came to feel that the anti-Vietnam protests were ‘shabby’. Certainly, the violence that occurred on Grosvenor Square reflected poorly on the protesters and the police. Nonetheless, the rally beforehand was entirely peaceful and most of those who entered Grosvenor Square did not have violence on their minds. It may be unclear what exactly the leaders of the protest hoped to achieve – and there remains the suspicion that the VSC and Maoist splinter groups regarded it as a recruitment opportunity or the first sparks of a revolution – but it’s still possible to retain a great deal of respect for the unvarnished idealism that motivated many of the demonstrators who turned out that day. At least they cared.

Michael Rosen’s poem Arrests! has also been re-published on the website to mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Battle of Grosvenor Square’.