Civil Rights and Black Panther

by Steven Spisto | December 10, 2017

‘I don’t remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.’ – Edward Said

When the fictional superhero Black Panther debuted in Fantastic Four #52 in the summer of 1966, the Civil Rights movement was in full swing. Lyndon B. Johnson had just signed the Voting Rights Act, the Black Panther Party for Self Defence was founded the following October, and in 1967 the US Supreme court ruled in the case of Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional. For Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, two white liberal comic book makers, to introduce the first mainstream black superhero, it was an especially politically charged moment.

The Black Panther is a hereditary title handed down to the rulers of Wakanda, a fictional African kingdom and most technologically advanced country in the world. The current holder of the mantle, T’Challa, serves as king, spiritual leader, and champion of the people. T’Challa’s strength is made evident by his creators; he successfully protects his people and kingdom from harm, both foreign and domestic. Captain America, the living embodiment of the star spangled banner, has fallen prey to the Panther’s rage while attempting to chase Nazi’s across the Wakandan border. The Black Panther’s story arc reflects the historical and political context that the character operates in. Writers over the years have weaved in elements of historical conflicts involving invading powers like European colonisers as a means of asserting the radical political message the character represents. Such stories also traced an alternative history where un-colonised African countries, represented in Wakanda, may have developed free from foreign intervention. This poignant message came at a time when African nations like Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, and Zimbabwe were all gaining their independence.

Comic books aren’t immune from the unfair representation of African-Americans in popular culture, who are often being depicted in subsidiary or stereotypical roles. The characterisation of Waku, Prince of the Bantu, appearing in the 1954 Atlas Comics’ ‘Jungle Tales’ was reduced to a cheap stereotype. DC’s feature of Jackie Johnson, a black soldier, lacked agency and nuance—his creators rather used the character as a token minority. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s creation of T’Challa and Wakanda were pioneering additions to the genre. America’s first mainstream black superhero is one of the smartest men on the planet. A world-leading physicist with a PhD from Oxford – a modern day Einstein mixed with Tesla. Traits such as these subvert stereotypes peddled by the American media that often depict African-Americans as being uneducated and of low status. In this way, Marvel was a trailblazer for the representation of black characters as highly intelligent, politically powerful, and heroic.

My love of comic books brought about a realisation that representation within them has always been more meaningful than other forms of media, due to the significance of their narratives, and how central they are to forming a 21st century mythology. As an avid comic book reader I’ve always felt that the stories were imbued with teachings that have had a lasting impact on me. The colours, costumes, and mesmerising artwork were intoxicating but they couldn’t be anything other than superficial without an underlying message. As trivial as it may seem, Peter Parker and Clark Kent were always more present in my mind as symbols of virtue than Moses or Jesus. The weekly routine of Sunday School could never stand a chance against the hours I spent reading and rereading volumes of Batman & Superman. The sense of ownership which stems from collecting The Teen Titans fostered a deeper connection than either film or television ever did. Ultimately, the comic book canon has served as a source for those other mediums; it’s at the heart of our popular culture, and because of that, representation in it carries with it greater power.

Although Black Panther and Wakanda were a breakthrough in the depiction of black characters in mainstream popular culture, they still could not manoeuvre around flaws, partly brought about by the comic being a product of its time. Equality and self-determination were issues of political struggles in the 60s. Civil rights activists like Ella Baker and Bob Moses were agitating for the removal of state legislation designed to disenfranchise black voters. At the same time, Africans sought to install democratic systems of government to replace colonial rule. In the context of the contest for liberal values in the 60s, a hereditary monarchy seems too outdated a system of government for a country depicted as the most technologically advanced in the world. And so, inadvertently reinforcing tropes of non-western societies depicted as ‘un-enlightened’.

The motives driving Lee and Ditko, two white middle class creatives, should be questioned. It’s not obvious if they were moved by the ‘good visuals’, the publicity, or the potential financial gain that they could squeeze out of their black readership. In fact, Marvel was weary of courting too much controversy. In 1972, they briefly changed the name Black Panther to Black Leopard. Recently Marvel’s Vice President for sales triggered a media storm when he suggested, after a meeting with retail representatives, that the introduction of diverse characters was the latest cause of decline in sales. In fact, only two out of the fourteen representatives even suggested that argument, and other retailers soon came out to reject the claims. Reading through the older comics, and comparing them to more recent issues, you do get a sense that contemporary writers have given Black Panther a more political edge. Although I doubt that political motives played a significant part in Lee and Kirby’s original characterisation.

Comic book characters are ever evolving. Writers and artists are rotated on a regular basis: meaning that new story arcs are created, origins are reinvented, and histories are revised. Such is the case with Black Panther, which in 2016 was taken over by award winning writer Ta-Nehisi Coates and artist Brian Stelfreeze. Coates and Stelfreeze’s experiences as African-American’s added a layer of sincerity missing from the original run, bringing the character into a more active and sincere political discourse. In fact, Black Panther #1 (April, 2016) was the best-selling comic that month, thus contradicting the view that diverse characters don’t sell. The new series premiered at the same time as T’Challa’s first feature in Hollywood as a supporting character, but now, is set to star in 2018’s eponymous Black Panther, featuring a predominantly black cast. Black Panther does so much more than highlighting the importance of representation, it’s also creating a space in which black filmmakers and actors can thrive. In a recent interview the actor playing T’Challa, Chadwick Boseman said ‘I feel the energy. The image itself opens people’s minds up. You can talk about it all you want, you can have it in a comic book, you can even do an animated series, but when you see real people doing it, it changes something inside of you.’ The change Boseman is referring is a change I experienced a long time ago as a child, and soon, thanks to this movie, it will be something more people will get to enjoy.

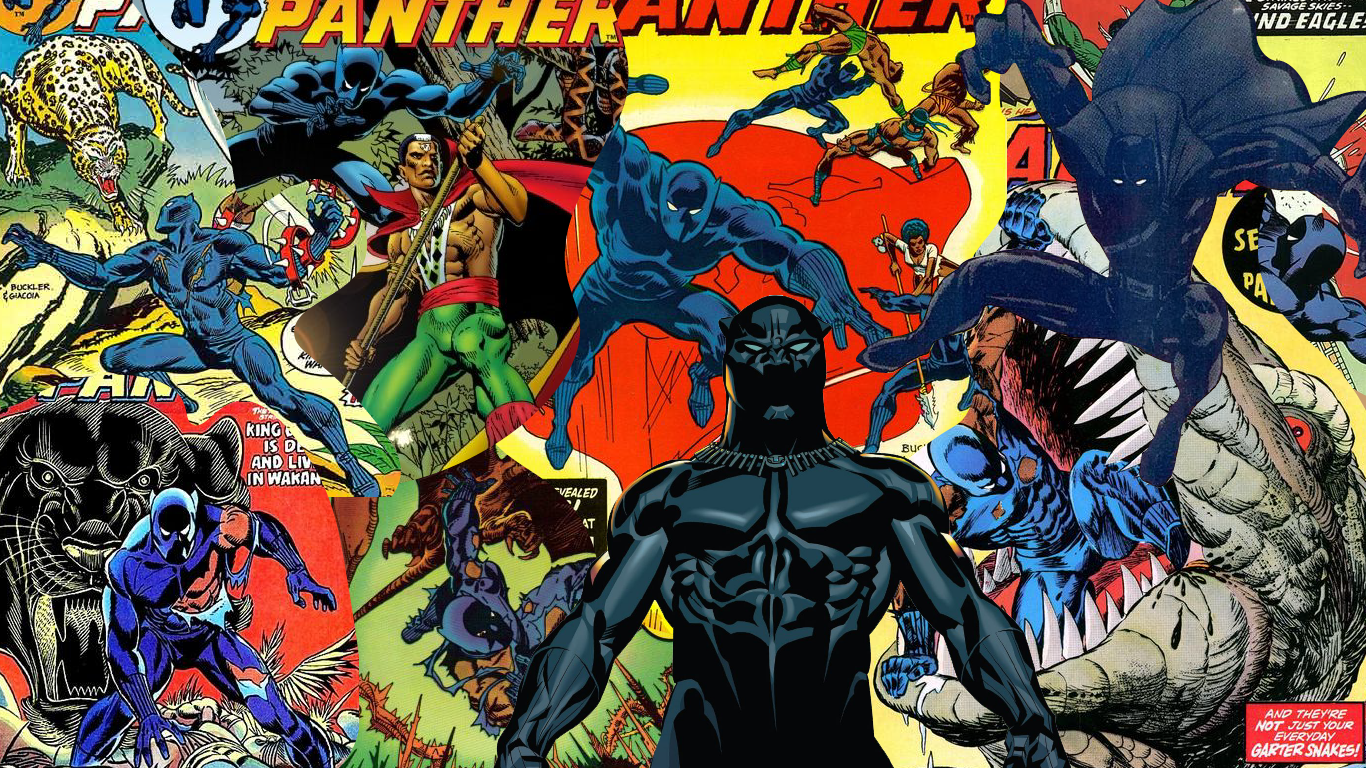

The creation of the Black Panther in the realm of comic books meant much more than just representation in the media, it symbolized a crucial development in the pantheon of heroes that form the modern mythology. The nature of comics as a visual medium means that they transmit ideas in the most striking and memorable way. The representation in comics are powerful, the way they mythologize characters, embedding them into our popular culture helps realise an understanding and enjoyment of each other. Black Panther has made me think more than any book I was ever made to read at school. Hopefully, it will provoke the same contemplation in everyone who watched the movie or picks up the latest issue.

Artwork by: Sholto Gillie