“Stop right now, if you can”: Interview with Clive James

by Lulu Smyth | May 5, 2016

Clive James is an Australian critic, poet, novelist and memoirist, best known for his television reviews and the autobiographical series ‘Unreliable Memoirs’. One of the most distinctive wits of the last century, he once described Barbara Cartland’s heavily-mascaraed eyes as resembling “two crows that had crashed into a chalk-cliff”, and Arnold Schwarznegger as looking like “a brown condom full of walnuts”. In 2010, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He speaks to Lulu Smyth via email.

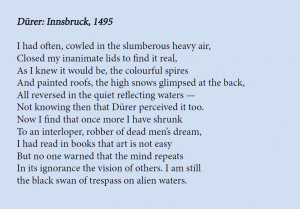

Since your diagnosis in 2010, you’ve been extraordinarily productive, particularly in the fields of poetry and criticism. ‘Poetry Notebook’, ‘Latest Readings’, ‘Sentenced to Life’, ‘Nefertiti in the Flak Tower’, and your translation of Dante have all been published in the last five years. A new book of collected poems and a verse commentary on Proust are coming out at the end of this week. In the face of mortality, what is it about poetry that draws you, rather than prose?

When the light is starting to fade, the nice thing about writing a poem is that you can see the edges of it while you are building it. Prose is too big. Nevertheless I might have a big prose book in the works soon, in which I can tackle large questions like this one. I’ve already got a title for such a book. Only a quarter of million words to go.

You were born Vivian Leopold James, but changed your name to Clive because “after Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O’Hara, it became a girl’s name no matter how you spelled it”. Do you ever wonder what your life might have been like if you’d stuck with Vivian?

The world-shakingly important matter of my change of name is treated fully in my book Unreliable Memoirs, but the best short answer now would be to say that if I had left my name as it was I would have spent the rest of my life fending off enquiries from people engaged in gender studies, and I would have never got anything else done.

‘Latest Readings’ was published almost a year ago. What have you been reading since?

Everything, but especially Jane Austen, still the gender student who matters most. Right at this moment I’m deep into Mansfield Park. There are half a dozen sets of the Austen novels in my family, and my younger daughter Lucinda has the best one: the neat little Novel Library set which I once foolishly gave to her instead of hogging it for myself.

I read somewhere that you’re a House of Cards fan, and so assume that you have Netflix. What do you think of the phenomenon of streaming television online?

Wrong assumption. I bought the boxes, and will buy the new season in a box when it becomes available. For my opinions on Frank Underwood’s political career, see my forthcoming book Play All, to be published by Yale in September. The New Yorker recently ran a piece of it: the chapter about Game of Thrones.

Thoughts on reality television?

I’m often asked to take the blame for the advent of reality television because I once screened clips from insane Japanese game shows. It’s like being held responsible for the battle of Okinawa. Declining to participate in Help, I’m a Celebrity: Get Me Out of Here was possibly my smartest career move.

With ‘Clive James on Television’, you went from being well-known to becoming famous. You’ve said in previous interviews that fame doesn’t change you, but it does change the way that people act towards you – the result being that you’re “no longer able to have a normal conversation”. How do you cope with that as a writer?

The only way to cope is to make coping a subject. I started to do so in the title essay of my book The Meaning of Recognition. There may be more to say yet; until, of course, the door finally shuts and there is nothing to say at all. I hope that my books, and especially the later ones, have managed to convey an essential sanity, but there were definitely times that I almost lost it. Some of my recent poems, in fact, have been about exactly that.

In the preface to ‘Unreliable Memoirs’, you wrote: “Most first novels are disguised autobiographies. This autobiography is a disguised novel.” In light of that, I was wondering what you thought about the recent trend of ‘autobiographical fiction’. Knausgard, Ferrante, Marias, Lerner etc, all exhibit a kind of playfulness and experimentation with the boundaries between those two genres.

My first and only reaction to Knausgard is that the world doesn’t need any more ordinariness than it already has. The women in my family have almost got me convinced that I should start reading Ferrante. I’ll do it, but she’ll have to queue up behind Jane Austen, who might not have exhausted all the playful possibilities of the novel, but certainly put a serious dent in the supply of playful possibilities that I could ever find interesting. Basically I don’t want to read any writer who is fascinated by his own technique. I’m not even fascinated by mine.

You’ve said that at both the University of Sydney and the University of Cambridge, you were “a bad student” who consistently read off-course. To the ears of my contemporaries, reading off-course is the sort of procrastination that qualifies being a good student. Now, with the internet, we have so many distractions that is almost impossible to stay focused on any one thing at a time, and work is scarcely one of them. Do you worry about the future of literature in this virtual environment?

Literature will win through the way it always has, by being too valuable to be ignored. All you have to do is write something as good as Pride and Prejudice. A cinch.

Finally, do you have any advice for young writers?

When the young writers ask me for advice, I give them the same advice as I give my niece: stop right now if you can.