What are we waiting for?

It’s an odd experience, waiting, in a generation like ours. Silence, space and solitude can be agitating in the twenty-first century, where a successful life is often synonymous with bustle and activity. Do we no longer know how to be passive?

Sure, the average city-dweller’s daily life is underpinned by some definition of waiting: we wait at bus stops, for kettles to boil, for friends to arrive. A study by Richard Larson claims that the average American spends two years of their life waiting in line. Yet the omnipresence of technology and virtual company means that we rarely immerse ourselves in a state of ‘non-doing’. And in situations where waiting is non-negotiable, such as in a traffic jam, the frustration can become unbearable. According to neuroscientist Daniel J Levitin, the brain’s search for new stimulation has “a dopamine-addiction-feedback loop behind it”. In other words, our modern dependence on distraction and activity equates to a psychological addiction. As I write this article, my patience is forfeited for diversion: I browse through social media and listen to music, succumbing to each tangent the internet offers me.

A manifestation of the way our generation waits—or refuses to wait—can be experienced, predictably, through Facebook’s instant-messaging app. It is no longer enough to simply send a message with immediate transmission—rather, these features contribute to a millennial anxiety of immediacy that demands incessant interaction. Highlighting this anxiety was the addition of a ‘seen’ feature, whereby the sender can see not only whether, but exactly when their message has been read. Since the introduction of this aspect, instant messaging has become something of a power play amongst young Facebook users: we have the ability to make people uncomfortably aware of the fact that they are waiting on our reply. It’s the 2016 take on waiting for the phone to ring after a hot date—except it happens all the time, and in a range of relationships. Not being the most recent person to respond, results in having the upper hand of not waiting for someone. If these conversational minutiae seem negligible, talk to anyone that’s ever flirted online and this aspect might reveal itself to be crucial to the interpretations of our virtual relationships. What about the way this same generation interacts as a part of a whole, that is, with the rest of the world?

Let’s consider that pocket of society we call activists. Remaining within the parameters of the internet discussion and social trends, we could note the increasing numbers of petition websites—such as SumOfUs or 38Degrees—which regularly channel a plethora of different causes to their members. These causes range from supporting individuals in legal cases, to curbing global warming. A subscriber to a couple of these myself, I know how easy it can be to ignore or delete these emails despite an aforementioned tendency to flit from internet tab to tab: we might coin these ‘unawaited’ messages of the average inbox. After signing up to these sites with perfectly good intentions, I started feeling like a kid creeping upstairs past TV-watching parents every time a new one appeared. Even when I do have time, the same wire in my brain that will readily vanish down a rabbit-hole of YouTube cats reacting to cucumbers, will habitually neglect to answer those pleas for action to really make a difference beyond ourselves.

In his book The Power of Now, German philosopher Eckhart Tolle examines the esoteric meaning of waiting, making a distinction between the situations I have just described and a more conscious state of presence. In contrast to the distracted, restless waiting we’re so good at, he believes there is ‘a qualitatively different kind of waiting, one that requires your total alertness.’ Implied is that we are a slave to the first condition and disconnected from the second; perhaps unsurprising considering the influence of digital information on our world today. What I find interesting is Tolle’s use of the word “alertness” to describe that which we are lacking. It aligns itself with journalist Bertie Brandes’ comments on the subject of drug use in the millenial generation, which identify an increasing tendency to seek refuge in psychological oblivion. “Where there was once tension, there is immediate gratification”, he says, classifying this predisposition as “engender[ing] a kind of paralysis.” We end up with a portrait of modern life that customarily stretches us with stress, distraction and remedial self-sedation.

If we take a step back from the neuroses of social media and glance at the bigger picture of what our generation’s future may look like, there is one thing we are good at waiting for. Every day the progression of climate change from a distant prospect to an imminent reality becomes more noticeable. Shortly after fracking plans were announced in UK’s national parks, a vast region of Cumbria saw itself dramatically flooded. Our most topical political issue of 2015, that of the Syrian refugee crisis, owes itself in part to a lack of water in the Arab regions. And it was hotter in New York last Christmas Eve than it had been on the fourth of July. Regardless, the vast majority of us sit and wait, content to turn a blind eye when our personal interests are not at risk.

When we link this passiveness back to the contrastingly attentive dynamics of social media, I can’t help but notice a regression on the part of the Y-Generation from the macro into the micro. From a collective consciousness to an egoistic disorder masquerading under the veneer of ‘virtual connection’. These symptoms intensify as the global population increases, and express themselves in the skewed values often seen in this our future generation. We need to reverse the bastardised model whereby we anticipate with every inch of our consciousness a briefly awaited Facebook message, and yet cannot have the foresight or drive to move past a passive waiting for more serious issues. The time is indeed now: our wait is over.

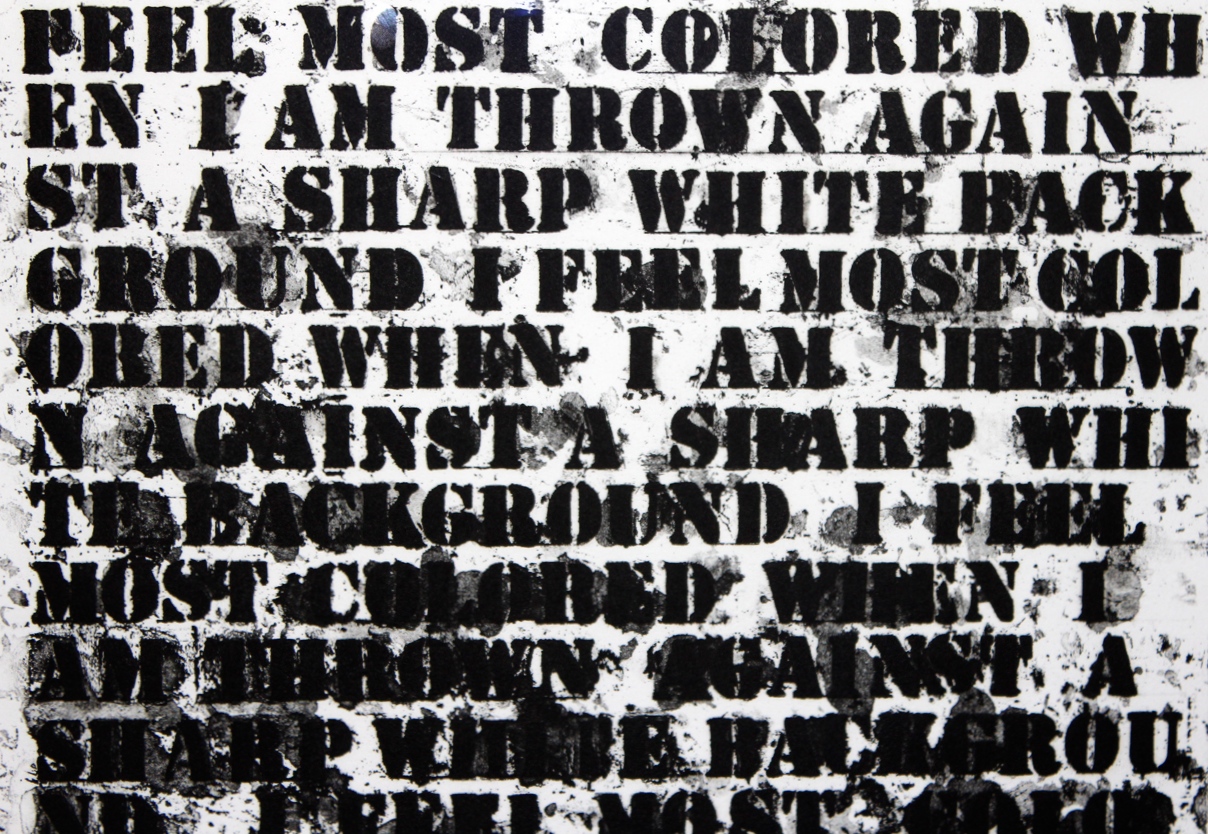

Image by THOR