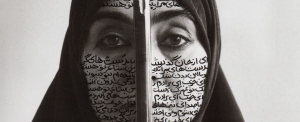

New Bodies, Old Norms: Transsexuals in Iran

by Thea Slotover | May 5, 2015

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, ‘male’ and ‘female’ are clearly defined oppositional concepts. Yet the country is also the world’s second most prolific practitioner of sex-reassignment surgeries. In 1985 Ayatollah Khomeini issues a fatwa stating that transsexuals should be permitted to change their sex, with radical surgery offered as a ‘cure’ for those suffering from gender dysphoria. Today, the government provides half the cost of sex-reassignment, as well as social support for those looking to undergo the operation. Iran is particularly unique in allowing post-op transsexuals to change their name and sex on their birth certificate and identity cards, providing them with a ‘clean slate’.

This seemingly progressive attitude is not echoed by all tiers of society. Though it was sanctioned by Khomeini, the socially conservative majority in Iran still find sex-reassignment very difficult to accept, with many transsexuals reporting complete rejection from their families following their operations. The subject, little discussed before the millennium, is being given increasing coverage by the state-sponsored media, coverage that aims both to titilate and to present surgery as an Islamic solution to ‘deviant’ behaviour. It is usually through radio, television programmes and articles in the ‘yellow papers’ that Iranians become aware of transsexualism and decide to seek consultation, particularly those from provincial areas who must travel to Tehran in order to have the operation.

Iran’s official stance might be viewed as incredibly progressive, but toleration of sex-reassignment surgery is tied to a rigidly binary attitude to gender. Individual’s freedom to decide their identities is limited to choosing between one set of stereotypical gender expectations or another. Male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals must conform to the same strict dress codes and legal regulations as those designated female at birth. That includes not being able to get a passport without their father’s or husband’s approval.

Of course, there is the straightforward satisfaction to be gained from finally feeling comfortable in one’s own body. An interviewee from a 2005 study stated her reasons in simple terms: “I am a woman. I’d like to chance sex because I think society will accept me as a woman.” Post-op transsexuals commonly use the phrase ‘born again’ and ‘belonging’ to describe the sensation of inhabiting their new bodies.

Practical concerns are also a significant factor driving MTF transsexuals to undergo the operation. In a 2008 documentary, Be Like Others, the filmmaker Tanaz Eshaghian interviews pre- and post-op transsexuals in the surgery of Dr. Mil Jalali, Iran’s leading sex reassignment surgery specialist. Ali Asghar, a pre-op patient, spoke of constant harrassment and sexual abuse dating from their childhood to the present, both at school and at work, and of abuse by the morality police and revolutionary guard, all as a result of effeminate dress and behaviour. “When I try and work with men, they sexually harass me. And I cannot work with women because I am not a woman.” Ali Asghar hoped that if they altered their sex, they would find social acceptance.

The abuse suffered by pre-op transgender Iranians hints at the darker side of the government’s positive attitude towards sex-reassignment. Instead of a liberal attitude towards self-definition, it implies a social climate where marginal behaviour is not tolerated. If transsexualism is regarded as an illness, it is easy for the government to acknowledge the ‘problem’ and present a ‘solution.’ Other elements of the LGBT spectrum are not tolerated. As Ahmadinejad noted on his visit to the US: “In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals like in your country.”

Those who do not want to undergo surgery but identify as a different gender to that assigned at birth are at even greater risk of social exclusion. The night before his operation, Eshaghian asks Ali Asghar if they would have the surgery were he not in Iran. The response is “No”.

Though Iran’s medical authorities distinguish strongly between transsexualism and homosexuality (the latter is a capital offence), the level of social acceptance accorded to transsexuals has led many gay Iranians to chose the label ‘transsexual for public use.

During research in several Iranian cities between 2006 and 2007, Afsaneh Najmabadi – a professor of gender studies at Harvard – noted that many operates identified the impossibility of living with their chosen partner, couples with the intense social pressure to marry and settle down, as influences on their decision to change sex.

In Eshaghian’s film, the boyfriend of pre-op transsexual Aboush says: “I was kind of mean to him when he was in men’s clothes. If I can persuade myself that he is a woman it makes the relationship better… but only because of the way people treated us [before].” After Anoush’s operation, the boyfriend becomes cold and distant, and is reluctant to go ahead with their planned marriage.

Sadly, these developments are far from unique: many of those who change sex on order to marry are left by their long-term partners, who cite lack of attraction to their partner’s new body as their reason.

In order to dissuade homosexuals and lesbians from sex reassignment surgery, the government carries out a four to six month programme of psychotherapy and chromosomal tests to ascertain whether candidates are ‘true’ transsexuals. Colloquially referred to as ‘filtering’ this process has ironically created social spaces in which homosexuals and transsexuals, grouped together, are able to meet and compare experiences, as people living outside of social norms. Najmabadi describes meeting men who identified as homosexual when they spoke to her in private, but claimed to be unsure whether they were “gay or transsexual” in group meetings. She observed an emergent sense of solidarity between some MTF transsexuals and homosexuals, with transsexual support groups opening up weekly (non-governmental) meetings to gay men.

But Iranian society’s utter vilification of homosexuals has prevented a truly open discourse with transsexuals, many of whom speak with disdain for those who are ‘kunis’ (‘anal’). Vida, a MTF transsexual who appears in Be Like Others says: “I know homosexuals, and I speak to them, but I am not friends with them. I don’t approve of their behaviour; it is un-Islamic.” Having experienced life on the margins, transsexuals are more accepting that most Iranians but not wholly so.

The benefits of Iran’s policy towards sex-reassignment should not be dismissed; any measure that helps trangender people struggling with their identity to carve a comfortable position for themselves is laudable. But the Islamic republic’s blanket denial of alternative views of gender and sexuality has led to cases where surgery is undergone by persons who are not fully committed to it.

For these people, the eventual results are rarely positive. Their new physicality offers scant opportunity for sexual fulfilment, and – particularly for those who switch MTF – it is often difficult to find new employment. Following surgery, Ali Asghar (now Negar), disowned by her family, has been forced to make a living through sex work, and lives with three other MTF transsexuals from the same clinic, in the same line of work.

The only hope for a truly progressive and accepting attitude towards sex and gender can be found in the discourse opened by the policy. They have exposed a chink in the solid barrier between masculine and feminine through which future generations of Iranians might be able to transcend ‘solid’ ideas of gender.