“We marched out down to the Ashmolean where we burnt the proctors in effigy”: Tariq Ali on Student Activism and his time at Oxford (1983)

by Sue Irvine | April 28, 2015

We are sitting in his study in Hornsey, the seat he hopes to contest as a member of the Labour party in the next General Election. At the moment, the problem of his membership in the party has been ‘shelved’ by the NEC who regard him, basically, as too far to the Left. Hornsey Constituency Labour Party are willing to adopt him as their candidate, however, and the dispute remains unsolved.

But Tariq does not seem over anxious. He continues to speak at 3 or 4 meetings each week and generally disseminate his political convictions. “Since I left Oxford,” he says “my life has been a total involvement in socialist politics.” He began life in Pakistan where he went to University and was very active in student politics. “Pakistan was then, as now, under the rule of a military dictator. I came to Oxford really on the insistence of my parents, who wanted me out of the country before I was locked up indefinitely. Coming from a society where any talk of humanism was seen as almost worse than treason, I found Oxford very stimulating.”

But not, as he emphatically points out, academically. “Oxford was very liberating socially, sexually and politically, but I just ignored the academia. It didn’t interest me.” What did interest him was politics and he was a ‘direct-action’ Marxist at a time when you could count Oxford Marxists “if not on the fingers of your hands, then on the fingers of your hands and the toes of your feet.”

I wonder how Oxford could be so politically invigorating, but Tariq assures me that the Oxford of 1963-5 was a very different one from today’s politically tepid University.

“It was much more politically defined than your Oxford.” He suggests The Isis as a barometer of the current lack of politicisation in Oxford though he concedes that the Left is much wider here now than it was then. “But we were a much more intelligent bunch. Even the right-wing people seemed more open to ideas. Oxford in my day was in a transition period from the late ’50’s to the radicalisation which finally erupted in ’68. We felt as if we were on the eve of something important and it was very exciting.”

He was very active in the Labour Club and became President of the Union in his second year – the first Pakistani to do so. “You must remember that this was before the Left boycotted the Union. It was a genuine arena of political debate. I think the boycott is pointless, the left should be using the Union to convince people of their beliefs; it draws the largest audiences.”

When he stood for presidency, he was opposed by Douglas Hogg and recalls that “half of the Tory opposition front bench came down to cast their votes against me.” He won of course, and strangely enough on the eve of the ‘Queen and Country’ debate at the Union – in which he took part – whom should he run into but the unfortunate Douglas, forever fated to be crushed under the heel of Tariq Ali’s impassioned and concise delivery. The occasion was a Radio 1 debate on the very same subject, between Tariq and the ill-starred Douglas. “Listeners were asked to phone in and register their votes throughout the programme, and at the end, 10,000 people had phoned in, 6,000 of whom were on my side…”

He sees this result as more symbolic and realistic than the overwhelming result against the motion ‘This House Would not fight for Queen and Country’ at the Union. On one hand he described the Union audience a representative of the ‘silent majority’ at Oxford and on the other, said that he felt a close result on the motion would have been more representative of the students as a whole.

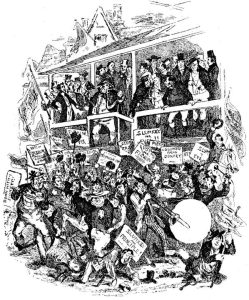

Tariq’s own contribution to television while president was a teach-in on Vietnam at the Union. Long before this official action in his second year, Tariq was making a name for himself as a man-of-action around Oxford. “In my second term the Union invited the South African ambassador to speak, so we arranged a huge demonstration and a barricade outside the Union, banging on the ambassador’s car and so on. Seven of us were sent down for ‘bringing the good name of the University into disrepute’. We were let back in later, but gated for a month so that I had to be in my Lodgings in Holywell Street at 9.30 every night – Bulldogs used to sometimes follow us round to check up on this. On the last night of my gating however,” (recounted with obvious relish), “We held a wild party at my place, and marched out down to the Ashmolean where we burnt the proctors in effigy.” Those were the days.

But going down was no anti-climax. He began his law degree at Gray’s Inn but soon gave it up to concentrate on politics and the Vietnam issue. “I was then asked by Bertrand Russell to do some things for the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation and to go on a fact-finding mission to Indo-China.”

Now, a great deal of his time is taken up by writing. He’s just finished a book for Penguin called Can Parkistan Survive? and is compiling an anthology for them entitles What is Stalinism? “Then I’m working on a book about contemporary politics in Britain and the debates in the Labour party for New Left Books and doing a new biography of Genghis Khan for Quartet.”

But Tariq’s last word is a criticism of the college-system which he thinks should be reorganised along the lines of other universities. “It’s an anachronism like the House of Lords and the Monarchy. Oxford is part of that complete failure of the English bourgeoise to institute a thoroughgoing bourgeoisification of the previous system. Now it has become an ideological pillar of the ruling class and when it gets threatened, they get upset.”

Determined to end on a final cheering note, I ask Tariq what he thinks of Cherwell. “Oh that dreadful newspaper – that was YUCK!”