The Man with the Backpack

The man with the backpack stands next to us on the train every morning pretending to read his book. We spend the seven minute journey to school trying to make him laugh or sigh, or, if we put on a really good show, glance up from his fake reading with an incredulous look. It’s an entirely involuntary motion, a flash of eye contact between a balding man in his mid-forties carrying a bag so antisocially large that it takes up at least two valuable commuter standing spaces in the busy train vestibule, and a group of teenaged girls. What? his face seems to say, half-irritated, half-amused. We crave this look.

The day my acceptance letter arrives, I’m embarrassed to admit how quickly my mind jumps to the man with backpack. He’s the first person I tell, actually, after my parents—my decision to break the good news to my friends on the train is heavily influenced by the prospect for spectacle such an announcement holds. Their shrieks of excitement and celebration are the perfect way to inform the man with the backpack that I am off to study English at Oxford. It isn’t so much a desire to show off (not just a desire to show off) as a need to update him on the situation; he knows which college I have chosen, has heard about the ordeal of interview, can probably even quote lines from my personal statement—I can’t just leave him hanging. The man with the backpack also knows the names of the teachers we love and the teachers we hate, as well as the ones I dismiss as “nice but ineffectual”, my euphemism for what I identify as their intellectual inferiority. My general air of youthful arrogance must be exasperating not only for my teachers but for the man with the backpack—but perhaps he understands that such levels of unmitigated confidence are inevitably unsustainable. Maybe he knows that what he is witnessing is a thing that can not and will not last—the peak and subsequent last days of my Rome, of the cosy, sheltered little empire which has spawned this arrogance. Perhaps this understanding is the reason for the strange sort of sadness in his smile upon receiving my good news. It’s not the smile I want, but it is a reaction and at seventeen I live for the reaction of a man whose name I do not know and to whom I have never spoken.

That’s not to say that the man with the backpack is a stranger. We know lots about the man with the backpack. We know that he has a wife with a backpack, who also wears thin, wire-framed and, if we’re being honest (and of course we’re being honest as we’re seventeen and secretly consider ourselves the definitive authorities on fashion in the Chichester area) unfashionable glasses, who gives him hasty kisses as they part on the platform every morning. Although we never really see him do it, we know that the man with the backpack likes to read—we imagine that he does finish the books he holds in his hands every day after we have left the train and he is all alone. As we point out to each other, it would be an expensive and quite frankly culturally wasteful endeavour to buy book after book just to hold and pretend to read during our seven minute train journey. We’re self-obsessed, yes, but not stupid. We’re seventeen. The man with the backpack is a varied and often controversial reader; we find his choice to read Twilight on a train full of school girls psychologically revealing (surely expressive of a desire to connect with us, his train friends, or perhaps a desperate grasp at the youthfulness with which we consciously taunt him on a day to day basis) and consider his propensity to read what we regard as commercial thrillers disappointing, though not altogether unexpected.

* * *

The train that used to take us to school was the Southampton to London line; for seven years we inserted ourselves into this man’s life, a small seven minute distraction between Chichester and Barnham, playing a part in his morning routine. We’d wonder about his job—such a big backpack surely contained something, but why he would have to lug this large something to and from the workplace every day remained a source of annoyance and mystery to us. I think that’s what he was—something mysterious, and yet familiar. We knew of him, but not about him. We wanted his attention, but I don’t know what we would have done if he had actually spoken to us one day, if he had participated in the conversations that were always really for him. I think we would have hated it. He would no longer have been the man with the backpack. He would have had a voice, an opinion, a mind and a reality other than the one with which we endowed him every morning at 8:08 on Platform 1 at Chichester station. He would care about more than my opinions, and, at seventeen, the loss of my greatest and eternally silent fan would have been too much to bear. I think he knew that.

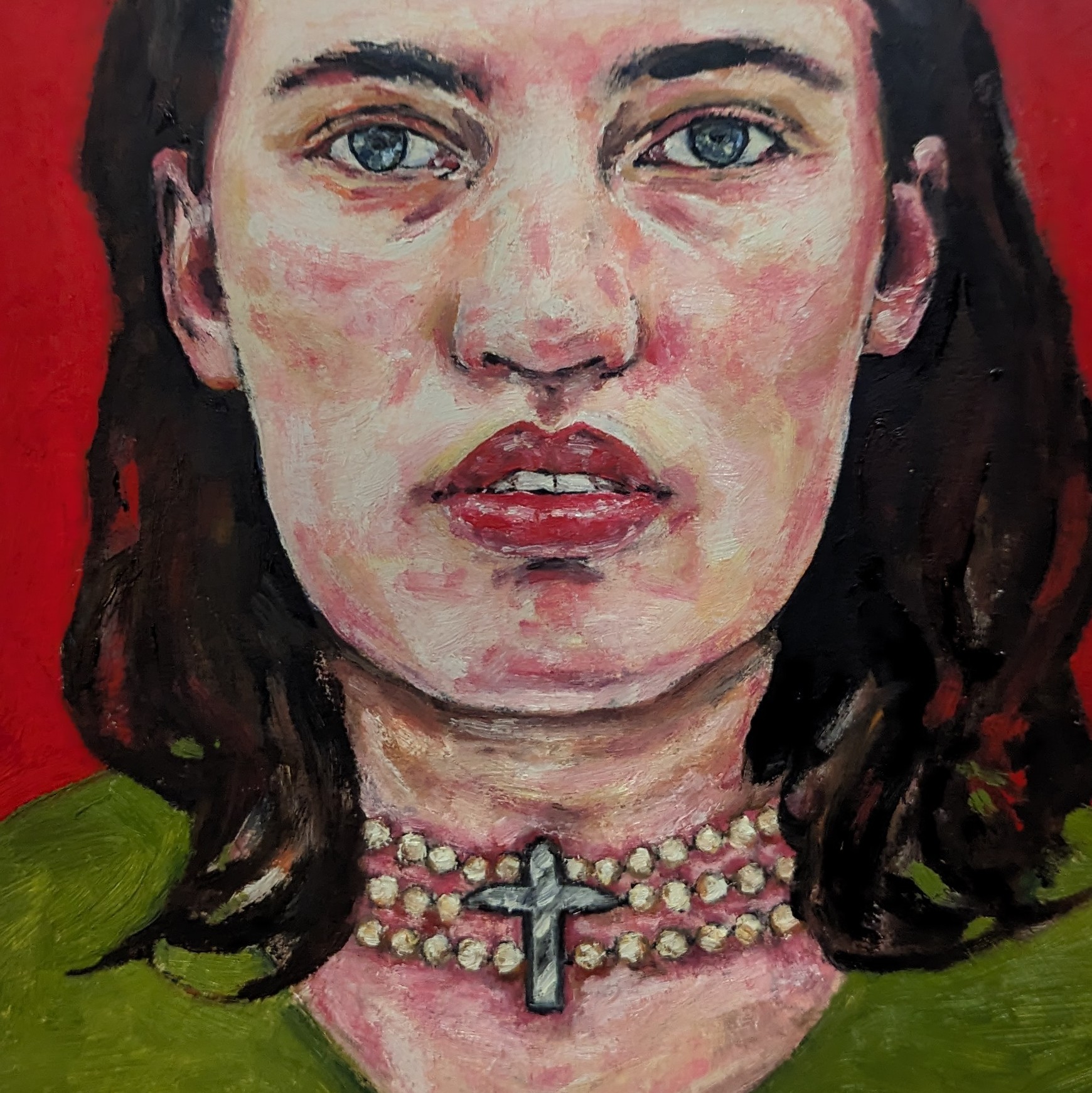

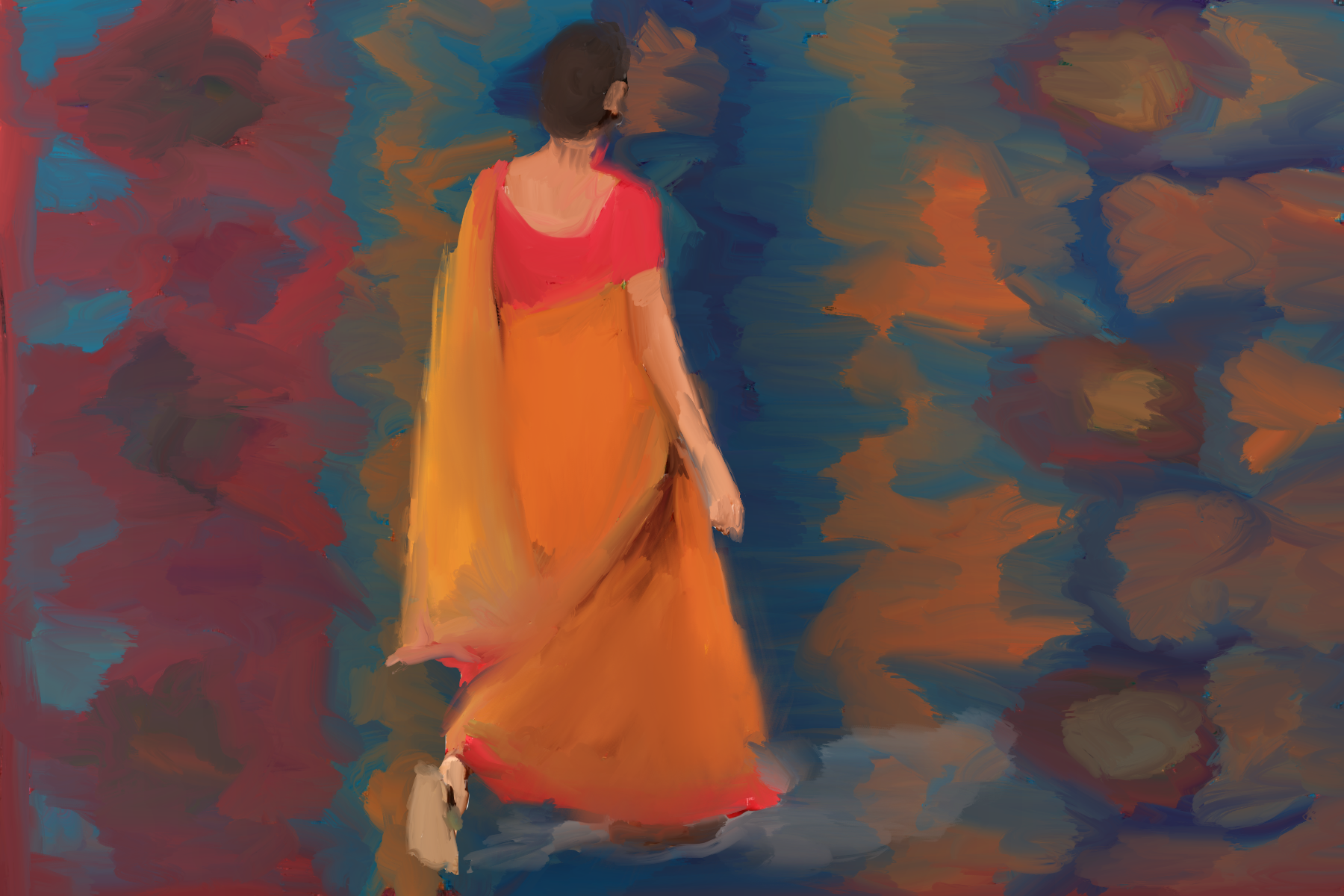

Image: Géraldine van Wessem