Eyewitness: Riots in Istanbul – Part Three

Saturday, 1 June 2013

Taksim Reclaimed

Turkey is a country built on the uneasy frontier between two of history’s most powerful and productive civilisations, so it is unsurprising that questions of symbolism often seem to transcend all else. Perhaps all politics are ultimately, at least in part, games played with symbols, but in Turkey they seem manifest, taking sides and demanding reckoning-with. There’s the fez, which Atatürk outlawed, and the headscarf, which his successors persecuted and Erdoğan has championed. The Turkish language, ruthlessly purified of foreign words at the birth of the republic, was once enforced as the vehicle of the ezan, the emancipation of which from this heresy was a bitter political struggle. After all, the language, with its modern Latin script that symbolises eternal allegiance to the West, is itself the great symbol of the nation – a symbol that many would never see compromised by Kurdish broadcasting, or Kurdish schools. It stands with the brimmed Western hat, the (originally Swiss) civil code and the nearly-built-from-scratch capital of Ankara as great national symbols, whose promulgation in place of the old Ottoman imagery of monarchy and Islam was Atatürk’s main achievement in securing the power of his secular republic. Nevertheless, it is Atatürk himself who has become that republic’s greatest symbol, a metaphor for the national longing to be strong, modern and respected by the West.

When I returned to Taksim Square on Saturday evening, the first thing that struck me was how the crowds – which had torn down street-lights, smashed windows and layered all of central Istanbul in spray-painted slogans – had lovingly decked out the monument of the War of Independence, and the statue of Atatürk at its centre, with flags and bunting. The square was alive as I had never seen before, buzzing with a sense of triumph, of renewed strength and victories to come. Tens of thousands of people had gathered, and they moved quickly and loudly across the crowd, either in large blocks or smaller gaggles, often starting loud and raucous chants as they moved through. Above the churning sea of people there were thousands of flags, both the star-and-crescent national flag and the various banners of the leftists, as well as the version of the national flag with Atatürk, in an immaculate Western suit and looking noble and distant, superimposed on the foreground. Around the square, columns of smoke rose from bonfires and the wheeled grills of entrepreneurial köftecis. Chants broke out, spreading across the crowd in steep, short crescendos, and mingling with singing and drumming. Little boys selling tea from thermoses strapped to their back, and old bearded men hawking Turkish and Atatürk flags weaved in and out among the lively protestors.

That evening I worked my way from the main square, up through Gezi Park and ultimately along Cumhuriyet Caddesi in the direction of Harbiye, the commercial district west of Taksim. Gezi Park was packed with people, all impossibly young. Most were sat in groups on the grass, drinking and smoking, and the chatter seemed to fill the air as much as the smoke and steam coming off the grills. The atmosphere here was more collegial, and with the feeling of a massive block party as much as a protest, unlike in the main square – where large clumps of people of the various different ideologies, communists and Kemalists, had moved in separate ways to different chants, a subtle reminder of the fault-lines beneath this united front. Gezi Park seemed to be the base of the less political – among whose number most protesters seemed to count themselves – who were here not for the great struggle but to challenge an arrogant government. I worked my way gradually across the park, stopping frequently to take in the impromptu concerts and folk-dances.

In Gezi Park, there was a sense of tranquility, as though everything to be fought for was already won, but as I continued down the muddy slopes at the park’s far end, I found myself at the corner of Cumhuriyet Caddesi, the wide traffic road that runs from the end of Tarlabașı along the edge of the park; here, the mass mood was of consolidation, and preparation. One man stood on an overturned car and pointed in the direction of Harbiye, warning that the police would come from that direction and that preparations needed to be made, and this had a ring of hopefulness to it as well as militancy – eagerness for the next glorious fight. For the moment, he didn’t seem to trigger any mass movement, although he had anticipated the turn the evening would take. I followed the avenue as far as Osmanbey Metro, about a mile from Gezi Park. The pavement was filled with people, flowing onto the street. Traffic was less than normal but still busy, and cars passed through honking their horns in a celebratory din, some driving up and down waving Atatürk flags and cheering, and the thick crowds surrounding them waved back and broke into chants in response.

Even at this point – it was around 11.00 when I decided to begin heading home – significantly more people seemed to be heading away from Taksim Square than towards it, though it was still full of life as I passed back through. The BBC had said earlier that the square was filled with ‘tens of thousands’ of people, unhelpfully. The popular statistic, which almost everyone I spoke to had accepted as fact, said that the number was three hundred thousand at its height, and the crowd was a vivid reminder of modern Istanbul’s most salient characteristics: it is a huge city, and a young one. Looking out several times over the tens of thousands, I couldn’t make out a single headscarf, and although later reporting did outline the contribution of ‘anti-capitalist Muslims’, the demonstrations had been taken on the initiative of the secularist and cosmopolitan classes who make up the backbone of the Kemalist establishment.

This is not a young person’s revolt, however – except inasmuch as Istanbul is a young person’s city – and it certainly wasn’t a middle-class one. Going to a small büfe near my flat for dinner, at about midnight, I didn’t have to ask the men working their for their opinions of the police, of the government or of ‘Tayyip’, all of which they held in sworn contempt. Cab drivers, fellow students and old men in coffee shops would all, in days to come, voice the same strident views. My university – the oldest and, I’m told, most selective in Turkey – offered to postpone exams for students who had been demonstrating, but shopkeepers and tea-vendors were no less likely to do what they could for the movement.

At about half midnight, I finished my chicken dürüm while the men in the büfe watched the television; as I left, the owner’s son announced a rumour he had just received by text, that the police had returned. This seemed improbable, given how thick the crowds at Taksim were, but I returned anyway to look around. I returned via Istiklal Caddesi, and as I crossed the main square the mood seemed to have changed. Perhaps it was because the less hardcore demonstrators had mostly left, or merely the effect of the dark of night on the psyche. In any case, I was more aware of the burnt-out police cars and public busses – windows smashed, tyres deflated, doors ripped from the hinges and everything layered in graffiti. Every access point was now choked with barricades, made out of overturned cars and torn-out car parts, abandoned police shields and barricades, and any number of benign civic fixtures; and they were rising and expanding constantly. There were fewer people but they seemed to be more animated, and everything was illuminated by the flickering of the surviving electric lamps, and the dancing light of the bonfire flames.

I crossed the main square to Gümüșsuyu, the upmarket diplomatic quarter surrounding a wide avenue that winds downhill from Taksim to the edge of the Bosphorus, which was the area rumoured to be under attack. It wasn’t, but I stayed to watch the barriers being erected – every few dozen yards, one had been started, although the one closest to Taksim Square was the most impressive. The side-streets were apparently being scoured by groups of demonstrators, dragging anything solid, metal and movable up to the barrier and throwing it on top, without much evident regard for structural considerations. The phrase ‘like Tahrir’ cropped up more than once. I sat on the low wall running between the avenue and a hedge-lined tea garden, now littered with piles of cheap plastic water bottles, shopping bags and cigarette ends.

There was an electronic billboard on the avenue’s central reservation, about twenty yards in front of the emerging barricade, which had been flashing lingerie and soft-drink advertisements all evening; after about an hour, a few people began to hurl rocks at it. This immediately triggered fierce reactions from those around – several people yelled ‘yapmayın!’ – ‘don’t!’ – and a few men approached the stone-throwers and began arguing energetically with them. Five minutes later, more stones smashed into the billboard, with the same reaction; despite all the argument, young men lumbered up to it armed with makeshift clubs and began smashing it. The glass proved surprisingly difficult to smash (one of the lesson’s I’ve taken away is how much what we think of as glass – from shop windows to bus windshields – is in fact some alloy of plastic, and doesn’t shatter nearly so satisfactorily as one might like) but after a while it gave in, despite the furious objections of those around at every stage, carried out in the gesture-laden yelling for which the Turkish language is so well suited. I watched the even dispassionately (all else aside, I was quite tired at this point). I could probably have found plenty to despise about the billboard, and certainly about the crass variety of consumer capitalism that had built it – and I imagine many feminists would also have had no problem destroying the heavily-airbrushed images of the lingerie models – but these considerations were foremost on no one’s mind. It was simply the inevitable unleashing of the will to destroy, the original sin of all political violence, pushing itself against shaken inhibitions. In the end, as it often does, it won out here: the glass was smashed, the huge paper adverts were ripped out of their rollers, the bright fluorescent lightbulbs were shattered.

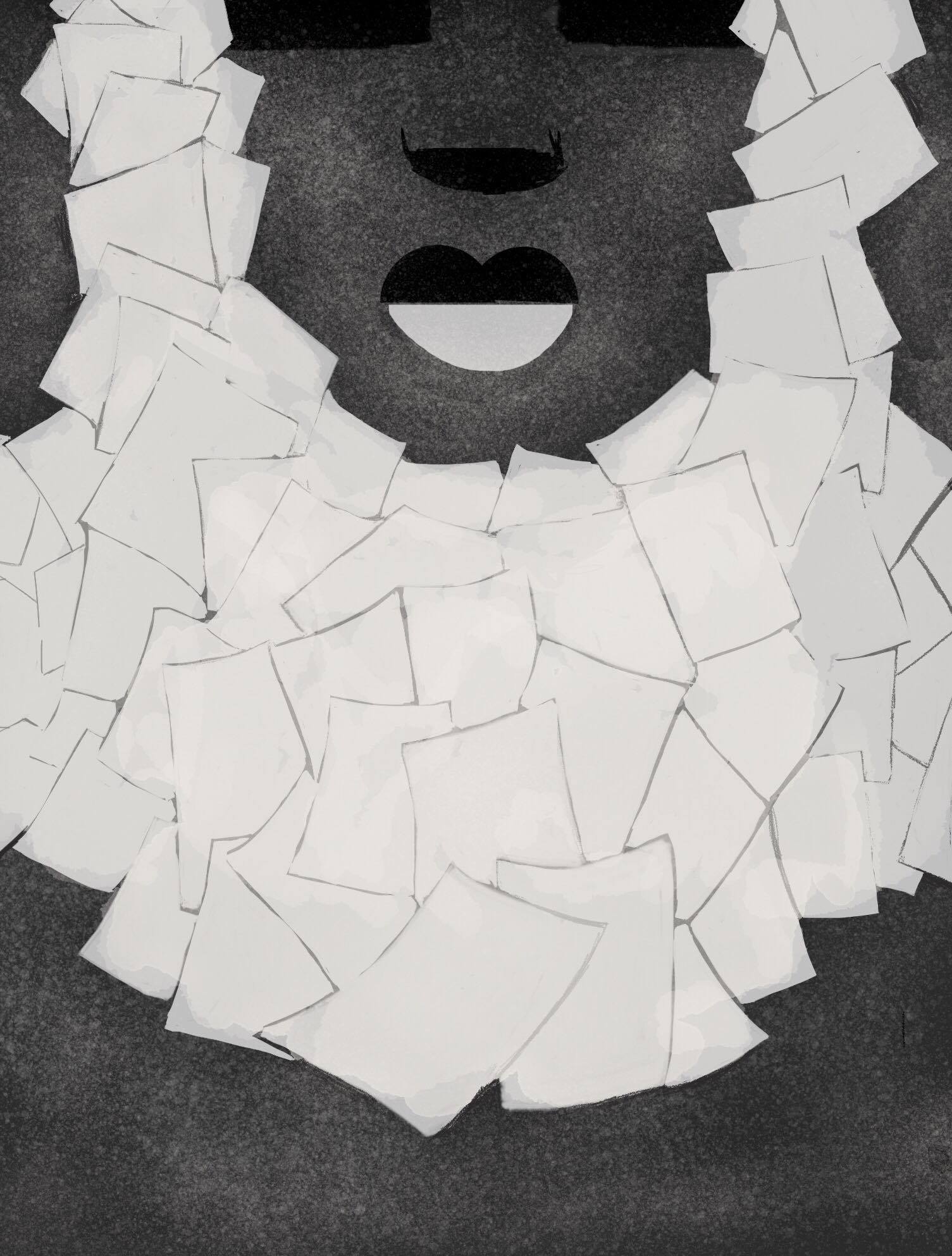

In fact, however, the destructiveness of the Gezi Park demonstrations has, in some ways, been surprisingly limited. On the one hand, vandalism was not just an accepted fact but an approved weapon of resistance – ‘I have become a vandal,’ a friend told me proudly, and for several hours a group of my university friends wandered through the streets around Taksim accompanying an art-student friend, finding places to spray-paint the graffito he had spent the day imagining and realising (a rather clever piece of art, I thought, which turned the AKP’s lightbulb logo into a gas mask). Several groups of girls stopped to admire his artistic skill and panache as a spray-painter, and as a group we wandered through the urban moonscape of spray-paint as connoisseurs, appreciating the most original and technically-talented pieces. No one tried to stop the dozens of vandals wandering around Taksim, and passing strangers often helped them to clamber into difficult-to-reach spots. Vandalism on a scale I had never before witnessed had become the language of the people.

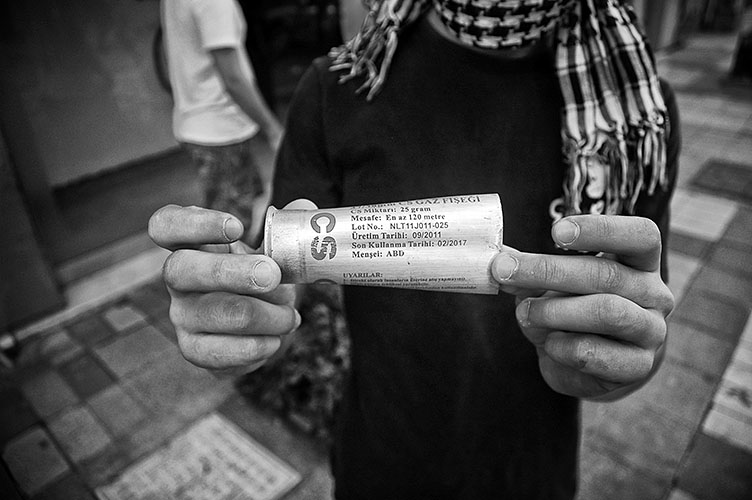

Yet there were also very strong inhibitions, for such a large crowd in such adverse conditions. Later in the week, when we were at Gümüșsuyu, a lull in the tear-gas attacks was interrupted with the sound of a window being shattered in a grocery store. Shouts of outrage immediately broke out and hundreds of demonstrators descended on the spot, some pulling back the culprit, the rest raising both hands to signal their rejection of this action; ‘provocateurs,’ one of my friends said, and from his timing and the crowd’s reactions it seemed plausible. To be sure, the rows of smashed windows everywhere in the region of the demonstration could not all be chalked up to provocateurs. Still, beyond this I have seen no evidence of looting, for example, and I have never seen a bystander targeted by the demonstrators. Erdoğan would point to this violence as some sort of proof of the demonstrators’ wickedness, but given that it began when his police used overwhelming force on a sit-in in a pre-dawn surprise attack – and considering how remarkably inhibited the crowds remain, despite every police provocation – they seem to have reached a good balance.

Whether it will remain a good balance, like all questions of what will next occur in events like these, is impossible to say. Istanbul has had a rough time of it lately. It lost the empire it very much considered its own in the wake of a cataclysmic defeat just as the century began. Having been successively the capital of three of the most powerful empires in history, it was put under British occupation for a spell, and even when it emerged from this humiliation it found itself in an unstable new state on the periphery of the world, surborned to a no-account provincial town that had usurped its position as capital. The palaces of the sultans and pashas became bureaucratic outposts for a state the Turks have never really come to love, and the Sublime Porte itself was reduced to a provincial administrative centre. The city’s pulsating ethnic diversity faded, while decades of misrule and economic decline dragged the country down, dragging Istanbul – which, like Rome from which it had once wrested rule of Europe, had once been called an immortal city – deep into obscurity. Only recently has the city, like all of Turkey, bounced back, but it has done so at a giddying pace. Tourism has surged, and the city has cultivated artistic and cultural leadership as well; it has been a European Capital of Culture and of Sport, and has bid for the 2020 Olympics, as proudly acclaimed in signs across the city. Foreign languages once again intermingle with Turkish, and a fierce civic pride has lately focussed on the clean, hyper-modern new metro, my opinions about which various Istanbullus have on several occasions eagerly solicited. It is a 2500-year-old city alive with the fervent anticipation of things to come.

As the city grows into its restored identity as a self-confident, cosmopolitan metropolis, it also seems to be struggling to find the appropriate symbols for this. The neo-Ottoman symbolism that Erdoğan has espoused has clearly not sufficed, not least because it belies an equally Ottoman vision of the relationship between state and subject. For the moment, the old symbols of the republic seem to do. Later I returned to Taksim Square, and wandering among the burnt-out busses and information kiosks, I found a crowd gathered around a young man holding aloft a poster-sized photo of Atatürk, solemnly intoning the national anthem. Several other times, raucous chanting and folk-singing moved seamlessly into the national anthem, with everyone rising solemnly to their feet; and the Atatürk imagery had been decked out with even more enthusiasm by the demonstrators than shown by the state itself for the frequent national holidays. Before the protests, my friend Burak told me, Atatürk’s reputation was diminishing – not surprisingly, given that for all his real achievements as a secular moderniser, the man was no more a democrat than the sultans who had preceded him. Or maybe it is just a matter of official historiography catching up with popular memory, in which the sheer disdain his regime had for popular sentiment has never quite disappeared – to say nothing of his suspicion of cosmopolitan Istanbul. In any case, he has been temporarily rehabilitated as a symbol of the secular state against perceived Islamist encroachments, although Islam is not really the problem, but rather the do-as-I-please state, a vibrant part of his own legacy. The inherent disconnect will probably not be lost on people, but as Turkey tries to develop a real participatory democracy, it will likely focus, as it always has, on finding the symbolism for it. This explains how a somewhat ugly park became the banner of a revolt – Gezi Park was the symbol, not the cause, that popular anger had been waiting for.

The future is still full of pitfalls. Burak has objected strenuously to my vaguely ironic use of the word ‘revolution’ – ‘this is a reaction against dictatorship,’ he says, and the general attitude is of defending civil rights against a government bent on re-writing the social contract. One night, as Gümüșsuyu was again attacked, the crowd’s attention turned to the adjacent army hospital, chanting for the soldiers to intervene against the police – which, given the army’s ambivalent role in the troubled evolution of Turkish democracy, seems like playing with fire. Meanwhile, cries of ‘yol aç!’ -‘make way!’ – announced the carrying of the seriously wounded through the throngs, and as the human toll mounts (three are so far confirmed dead), I wonder if anger and frustration may soon overtake basic humanity. Luxury hotels in Taksim have turned their lobbies into makeshift clinics for the injured, but someday the managers will want them back; the shopkeepers who handed out lemons will soon want peace again, and the masses who backed the demonstration will want public transport fully resumed. On the other hand, my friends have spent evenings seeking out clashes – ‘Barbaros was the best,’ one says of the especially brutal fighting in Beșiktaș, clearly already committing it to an idealised place in his memory – and there is no reason they should not continue to do so; all the while, it may not always be so easy for the different banners under which the demonstrations have raged to find common cause.

Erdoğan, by contrast, remains popular in the villages where most Turks live; he has a rock-solid parliamentary majority, two years until the next general election, and an enduring determination to get his way. He may yet be felled – some of his party seem to be moving against him. But he seems unwilling to budge on the broader points, and so the demonstrators may be faced with an increasingly uphill task. Reclaiming Taksim, for all the tear-gas, was the easy part. The coalition may splinter, but at least it has shaken the notion of Erdoğan’s invincibility, and indeed the state’s invincibility. This is no ‘Turkish spring,’ a term which betrays ignorance of the Turkish context that can only be ascribed to a monumental arrogance (although neither is it a ‘Turkish Occupy’, which gives the Occupy movement far too much credit). It is a movement for a democracy in a society that has traditionally only ever known autocracy, some of it electoral, and it is also the attempt to find some symbols for that movement. Hopefully – inșallah – it will help bring about a democratic nation as durable as Atatürk’s secular state.

http://occupygezipics.tumblr.com/