Illicit Portraiture

Fascination with what the Pre-Raphaelites did with their willies tends to get bums on seats. Effie, an all-star film directed by Richard Laxton (May 2013), will take as its subject the marriage between the polemical critic John Ruskin and Euphemia ‘Effie’ Gray, and their scandalous annulment on the grounds of non-consummation. In the wake of this, it is likely that the Pre-Raphaelites will be [portrayed as?] even more beleaguered by lazy sensationalism than usual, if not in the film then almost certainly in the publicity that it generates. Both the real and fictional sexual transgressions of those naughty Victorians will be obligingly ransacked from the art-historical dressing-up-box at around the time of its release.

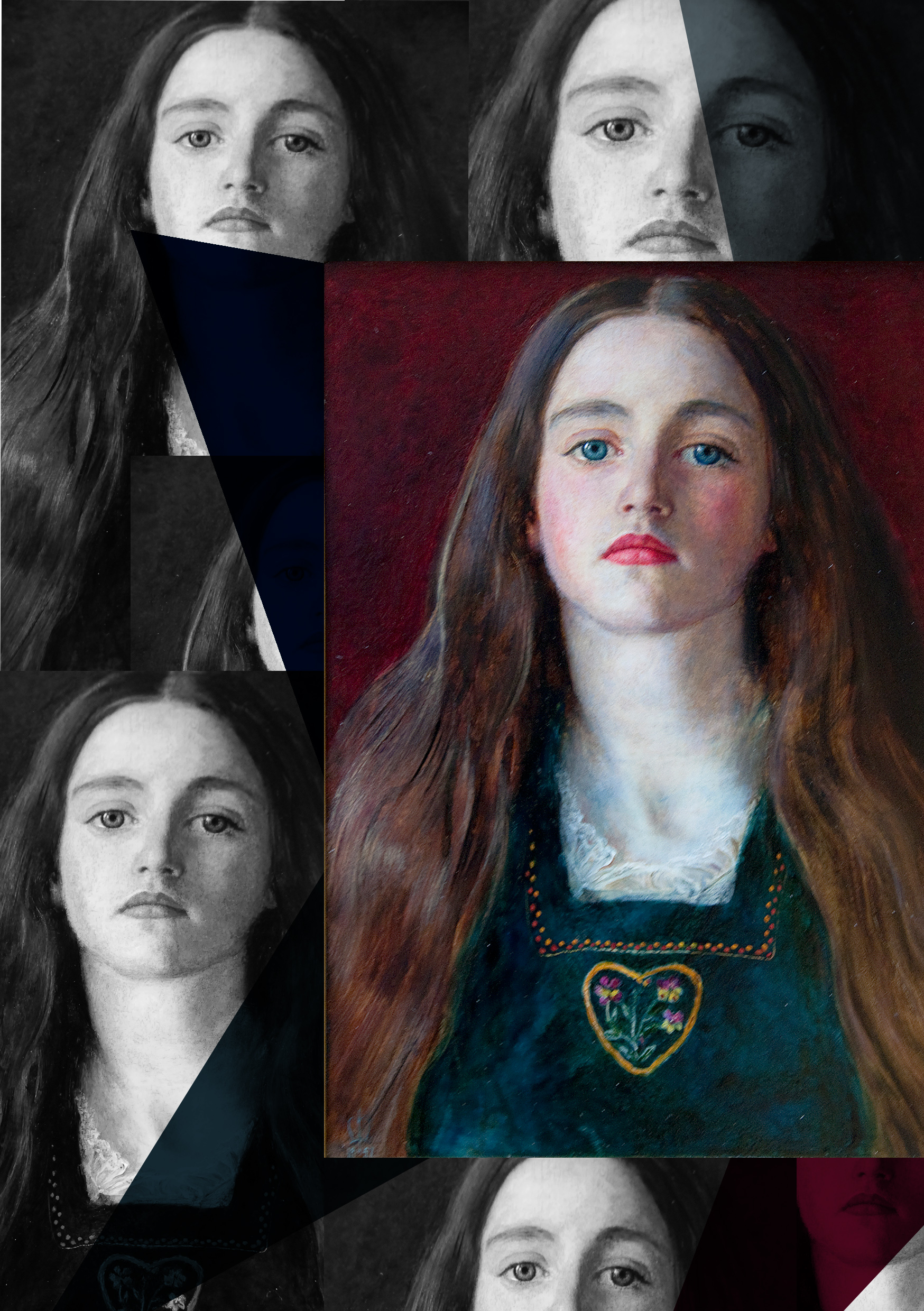

One such sexy story is that of Sophie (or ‘Sophy’) Gray, Effie’s much younger sister, and her alleged affair with Effie’s second husband, artist John Everett Millais. So the story goes: Millais and Sophie shared an illicit attraction, the main ‘evidence’ for which is the artist’s extraordinary portrait of his sister-in-law aged 14, painted in 1857. Thwarted love for Millais supposedly led to Sophie’s all-too-real subsequent mental breakdowns, culminating in her premature death aged 38. Certainly Millais found Sophie’s beauty remarkable; he observed it in a letter to her mother in 1854. Sophie did sit for Millais several times and it is apparent that they were close. Not unnaturally, speculation as to the exact nature of their relationship has been rife, resulting in the creation of what is essentially a Pre-Raphaelite fan-fiction, supported by crude inferences from the aforementioned painting.

In the artwork, Millais presents Sophie in the form of an intimate head and shoulders portrait of 12 by 9 inches. Sophie, seen before an ox-blood background, is blossoming; a Caledonian beauty, with long, shiny hair and unsmiling peony lips. Her chin wilfully tilts upwards, as she impertinently meets our gaze with alert blue eyes; she does not feel the need to put the spectator at ease. There is the mildest suggestion of wit behind her churlish expression, as though the artist and model share some sort of private joke; we see her raised eyebrows, and there is an easy intelligence in the sensitivity of her expression. We are also wise to a hint of adolescent self-consciousness in her flushed cheeks. The mutual regard between Sophie and Millais is palpable in their frank confrontation of one another as equals. How can we account for this directness?

It is important to regard the complexity of the sympatico between artist and sitter. They had shared personal stakes in the traumatic extraction of Effie from her marriage to Ruskin. Sophie was an active agent in this process, and bore witness to the very public ramifications of this perceived transgression (and it was a transgression, Queen Victoria socially shunned the young woman). Sophie was caught in a fraught and toxic environment; John Ruskin’s mother, a formidable character, attempted to cultivate Sophie as her little creature, dripping poison into the then ten-year-old’s ear about her sister, and using her as an emotional bargaining chip against Effie. Since Effie and Millais could not meet face-to-face following the whispers surrounding their initial acquaintance (which were, incidentally, actively encouraged by Ruskin), Sophie facilitated communication between the two. Effie was concerned at Sophie’s exposure to the cares of the adult world at a formative age; indeed she was an inordinately important figure in the liberation of Effie from her marriage, with a cumbersome burden of responsibility. How damaging this must have been for a bright and perceptive child can only be guessed at.

Sophie was well aware of Millais’ hopes and fears, even his heart’s desire, perhaps more than anyone else in the world. The nakedness of his painting of her is a brute acknowledgement of their unconventionally candid relationship, their bond sealed in their shared battle-scars. Critics describe Sophie’s expression as ‘knowing’; sure it is, she was made preternaturally worldly by events in which she was a central protagonist. In recognition of Sophie’s acquired emotional precocity, Millais does her the great favour of depicting her without sentimentality. The fact that the two were close is without doubt; to say that their relationship was necessarily romantic is a denial of its true complexity.

Who can say why Sophie’s life played out as a tragedy, culminating in a pitifully sad death. It may be diagnosed as the hangover of a dysfunctional childhood, unhappiness in adulthood, or perhaps simply a pre-disposition to mental illness; one certainty is that both Effie and Millais were stricken with grief at her decline and death. It is yet to be seen whether Sophie features prominently in Effie – which, admittedly, will be a must-see. After all, one cannot help but harbour a guilty curiosity as to even fictional accounts of what exactly the Pre-Raphaelites did with their aforementioned appendages.