Heaven on Film

In one Blackadder episode, Rowan Atkinson as a Cardinal tells a dying nobleman that Heaven “is for people who like the sort of things that go on in Heaven, like singing, talking to God, and watering pot plants.” Horrified by the prospect of spending eternity like a virtuous old age pensioner, the nobleman opts for Hell.

Apart from the difficulty of getting family and friends to join us on the path to salvation, there is the anxiety about the amount of carry-on luggage allowed – whether favourite books, meals and board-games can be brought along – and the concern that even the thrill of ‘Articulate!’ and ‘Settlers of Catan’ might wear thin after a few millennia of bliss. Only in films can we experiment with various dreams – and nightmares – of what the afterlife might entail.

* * *

The 1946 classic A Matter of Life and Death opens in the disintegrating cockpit of British air pilot Peter Carter, who manages to quote some heroic poetry before crash-diving into water without a parachute. But when the supernatural agent dispatched to bring him to the next world gets lost in the fog over the English Channel, Carter washes up alive on the English coast, where he manages to get engaged to a wholesome American girl called June. When the agent finally catches up with him, he refuses to leave his earthly life, and lodges an appeal in the heavenly court of justice. The climactic courtroom scenes foreground international conflict with R.A.F crews, Red Cross nurses and Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps soldiers, gathering in a magnified version of a U.N general assembly. Peter’s case somehow becomes an issue of national identity as the two sides attacking each other’s plumbing and pop music. The British government originally suggested the film as a means of lessening public hostility towards American servicemen stationed in the U.K, who were seen by many as overpaid latecomers to the war. This Heaven is political, full of clerks and the angels’ wings are wrapped in plastic.

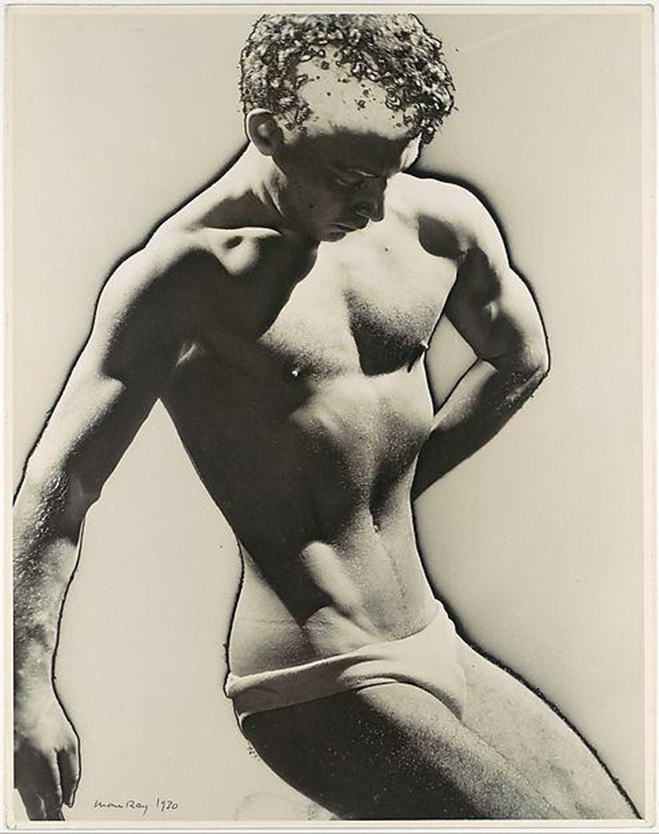

Comedians Peter Cook and Dudley Moore take on God himself in the 1967 comedy Bedazzled, a modern update of the classic tale of Faust. Faust here is played by Stanley Moon, a downtrodden Wimpy Burgers employee who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for seven chances to win over the girl of his dreams. The paradise of Bedazzled is just as stuffy as the bureaucracy of A Matter of Life and Death, consisting of a large Victorian greenhouse and orderly gardens tended by St. Peter. God is a disembodied voice booming “on thy belly shalt thou go!” and “dust shalt thou eat!” from the greenhouse ceiling. The movie ends with the devil’s rant against the exacting standards of Heaven and its tyrannical creator, whom he addresses as “you great git”, crying out “no wonder you’ve so few friends; you’re unbelievable!”

The Heaven in Monty Python’s 1983 The Meaning of Life, exerts a tyranny of a very different kind. It caters to its inhabitants’ every need; Mary and Joseph promise “gifts for all the family”, the Three Wise Men emerge with shopping carts to offer “the latest video games”, and a grinning, glittery-suited host offers hourly screenings of The Sound of Music and the entire series of Jaws. The catch is that there is no catch; Heaven is a supermarket without price tags and a hotel without bills. The dead luxuriate in an ecstasy of consumerism, unhampered by any sense of personal responsibility or ethics, and however obvious the cables behind the scantily clad angels and the artificiality of the snow, it is all too easy to get caught up in the joy of the performance. We do so, however, with the uneasy sense that we are surrendering part of ourselves to the impersonal happiness of shopaholics.

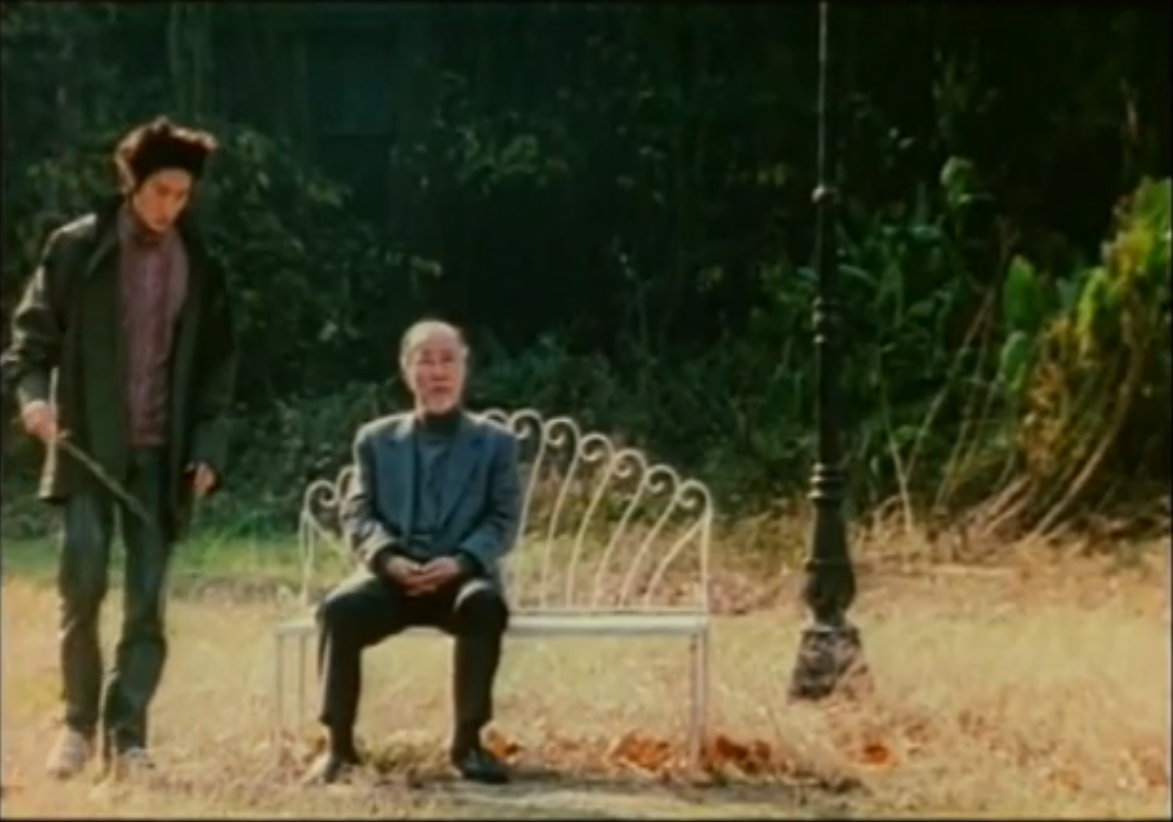

The 1998 Japanese movie After Life takes an approach far removed from the glitz and glamour of show business. The dead arrive at a box-shaped, dilapidated building in the midst of a desolate landscape and a team of counsellors inform them that they have until Wednesday to choose the happiest memory of their lives to be screened over and over. One character cannot recall any happy moments, another refuses to choose, and a third simply requests the sight of cherry blossoms. The production crew accordingly scatters balls of cotton wool, which she views with wordless rapture. This time is all about the Heaven of the individual. A young girl initially picks the memory of riding on the ‘Splash Mountain’ roller-coaster in Disneyland, but balks after being told that she is one of a hundred to make the same choice. She eventually chooses something personal, individual: the memory of being held by her mother.