Passing Through a Former Front Line

The main tramline into Sarajevo runs along a stretch of road once known as Sniper Alley. Its main landmark is the Holiday Inn, a squat building panelled in plastic tiles, yellow on the bottom, brown on the top. The Holiday Inn has just one virtue: its entrance faces west, away from the hills once occupied by Serb snipers.

Officially, the siege of Sarajevo lasted from the 5 April 1992 to the 29 February 1996. It is the longest siege in modern history – a year longer than Leningrad and three times the length of Stalingrad. The besiegers were Serbs, the besieged mostly Muslims, with small numbers of Croats and Serbs. All were Bosnians. All spoke the same language. All grew up in Tito’s Yugoslavia.

The citizens of Sarajevo tried to preserve some normality amid the carnage. At least one tram would run daily along Sniper Alley, often a death mission for the driver and any passenger crazy enough to hop on board. Oslobođenje, Bosnia’s highly-regarded daily newspaper, was printed from the start of the siege to the finish. Sarajevo’s women carefully daubed their faces with homemade makeup before going out to face the shellfire.

What makes a Croat a Croat and a Serb a Serb? Croats are Bosnian Catholics, Serbs belong to the [Serb] Orthodox Church. Muslims, the third major group, are converts from the time when the Ottomans ruled the Balkans. Until the 19th century, religious affiliation was not linked to national identity. Catholics in Bosnia were simply Catholics. However as nationalism swept through the Balkans, the Orthodox increasingly identified with Serbia and Catholics with Croatia. Muslims found their own national consciousness, though it was not until the trauma of the 1990s that they found a name for themselves: Bosniaks.

An old joke. Three elderly Bosnian men sit in a café. The waiter asks them for their drinks. The first man requests ‘kafe’; the second man says that he would like ‘kava’; the last man, ‘kahva’. “Three espressos then,” says the waiter. The differences between Muslim, Croat and Serb speakers of Serbo-Croat are differences of inflection, no more.

The odd thing is that Bosnia is not a religious country. Church and mosque attendance is low. Sarajevo during Ramadan has a festive atmosphere, but not a particularly pious one. Some fast, though the majority do not. Sarajevsko, the local beer, sold in vast plastic bottles, is happily consumed in this mainly Muslim city.

Bosnia today has three presidents: one Serb, one Croat, one Muslim. It’s a peculiar system, the outcome of the Dayton Accords: a peace deal forged in twenty-one days on a deserted airbase in Ohio, under the auspices of the Clinton administration. Dayton divided Bosnia into two entities: the predominantly Serb Republika Srpska, and the mainly Muslim and Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In theory, the central government has power over both entities; in practise, Bosnia’s legislature and presidency are paralysed by distrust between the three groups.

At Dayton, Sarajevo went to the Federation. Some of the city’s suburbs went to the RS. And so the two entities face each other in the hills overlooking the valley of the Miljacka River. The Federation seeks to abolish the RS, and the RS to secede from Bosnia entirely.

Each entity is aggravating to the other. A tourist bus shepherds people from the centre of Sarajevo to the Tunnel Museum and back via the Republika Srpska. The tunnel is a monument to wartime resistance: an underground passage that linked Bosniak held territory, on the far side of Sarajevo’s airport, with Sarajevo itself. It was a lifeline, a conduit for arms, and the centre of a lively black market trade. In peace, a section has been cleaned up and is marketed as one of Sarajevo’s key attractions. The entrance to the building is a bullet-riddled family house; at the tunnel’s opening, visitors are shown a graphic video of the siege. They are funnelled through the tunnel, out of the museum, and through the Serb suburbs.

Bosnian Serbs don’t take kindly to this intrusion by tourists primed with tales of wartime atrocities. “The police [in the suburbs] make it tough for you,” Adnan, who works for the tour company, told ISIS. RS policemen used to stop the tourist bus on its way back to Sarajevo. “And they ask some questions, they take passports, but nothing serious.” He is keen to downplay it. The tour company has found a way to placate the policemen: they have hired a Serb driver. “Maybe that is the solution,” says Adnan, hopefully.

Adnan is 25 – he grew up in Sarajevo, and lived through the siege. But he would prefer not to talk about it to the tourists that come his way. “I’m trying to always pack [in] other stories, not just the war, so you always can talk about how we have good rafting, nature, hiking, you know… to find out how in the 15th and 16th century in Sarajevo, three, four ethnic groups lived next to each other.” But there is a significant obstacle: the tourists themselves. “The war is something that, you know, people like to hear about.”

Talking about the war means providing a narrative. And in Bosnia, that narrative is by no means settled. Bosnians Serbs will talk about the atrocities they suffered in the Krajina, a portion of Croatia bordering Bosnia. Bosnian Croats will talk of atrocities at the hands of Serbs, and Muslims. Bosniaks will talk of Srebrenica, the infamous massacre of 8000 Bosniak men and boys, by Bosnian Serb forces, in July 1995. In Sarajevo, the war is about Bosniaks as victims – almost to the exclusion of the rest. Understandably so: the largest group in the capital city, they alone had no motherland to turn to, in the shape of an outside nation-state; they alone had nowhere else to go.

Bosnia cannot bury its history. But Sarajevo flaunts it daringly, perhaps too daringly for hope of reconciliation. The Federation’s Serbs are deserting it in droves.

There is a memorial gallery in Sarajevo dedicated specifically to Srebrenica. Large photos, some black and white, some colour, are spaced evenly over those grey surfaces. Behind a wall are video testimonies from survivors – mostly women – who lost sons, husbands – and endured rape and displacement. The testimonies last more than 30 minutes: a litany of hunger, deprivation, death and more death.

The museum opened recently, in late July 2012. So far, most visitors have been foreigners, says Ena, a volunteer. There have been “very, very few local visitors”. She puts it down to Ramadan. They have plans to bring the museum to the attention of Sarajevo’s citizens, particularly young children: “Most of the children have heard about the genocide from their parents and the media, but were born later, after 1995, so they’re not really in touch with the whole war.” And the children in the Republika Srpska? “I don’t now about the RS, it depends on their willingness, I don’t really think they would… But we would hope so. We really hope.”

History lingers close to the surface. The bullet-riddled apartment blocks of Novo Sarajevo. The youthful tour guide who, as a child during the siege, stepped outside to play and had his leg pierced by shrapnel: “Here,” pointing to a scar, “And here.” The clusters of blinding white gravestones on the hills. The deserted Orthodox Church. The Tunnel Museum. The wandering amputees. Too much history for a small city, where Serbs and Muslims and Croats live cheek by jowl, no longer mixed together, but eyeing each other warily, the Serbs from behind a border that marks an autonomous entity, but not a separate state.

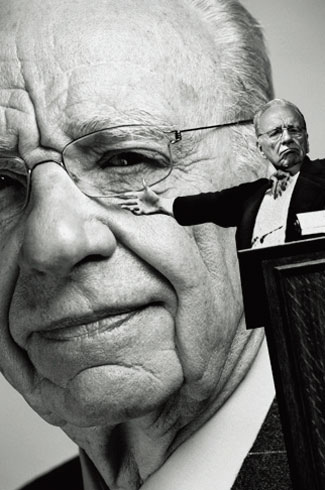

Photos by Peter Yeung