Einstein on the Beach

by The ISIS | January 25, 2013

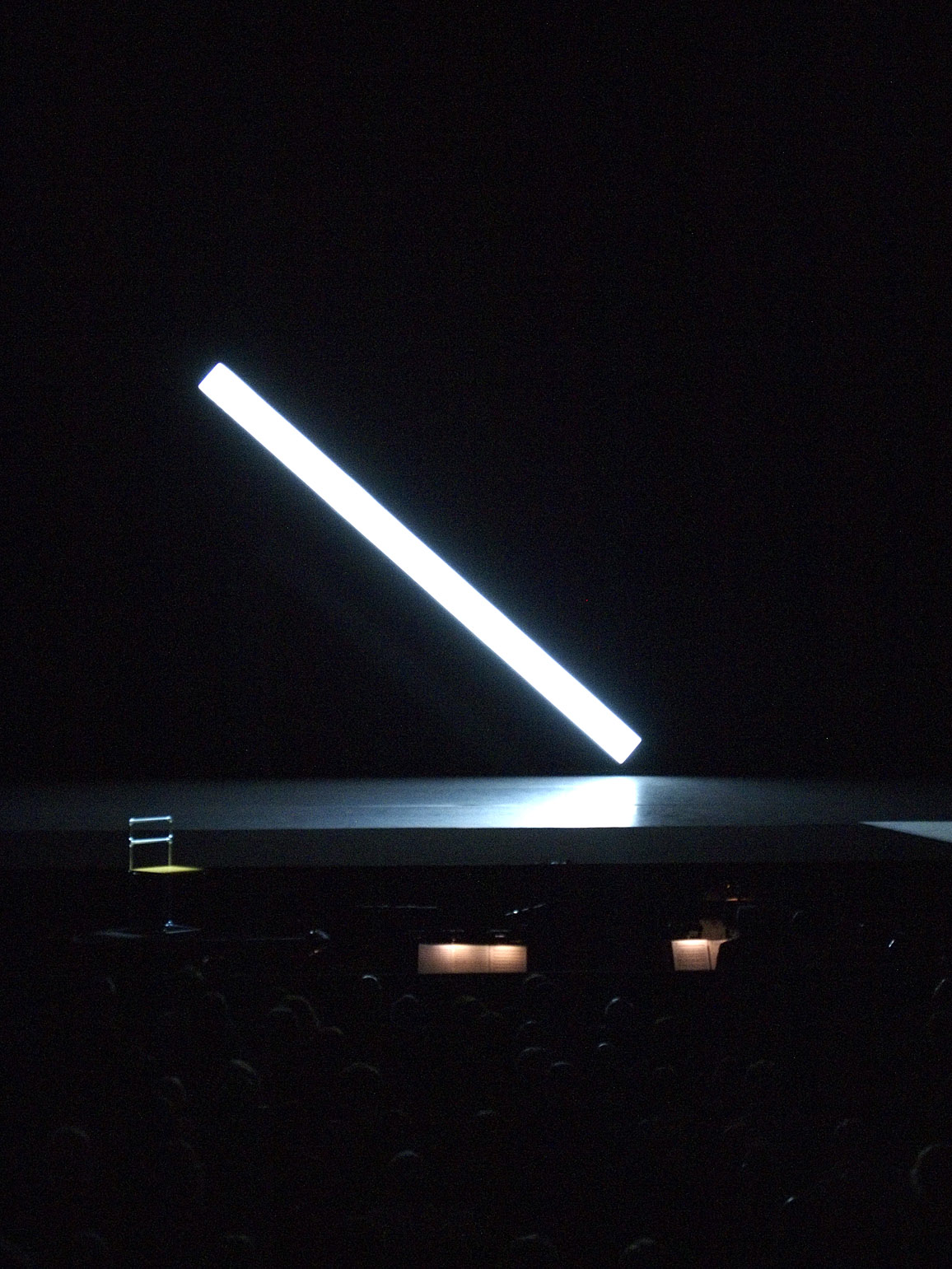

An enormous bar of white light lies horizontally across an empty, black stage; music plays that sounds like J.S. Bach wrote a final piece for synthesizer, on LSD. The light lifts slowly up at one end, becoming an ever-steeper diagonal, until it stands upright in the dark. Now the music shifts to an eerie, wordless soprano solo. At a glacial pace, the bar of light is lifted up through the void to finally disappear out of view. I watch the scene and forget to blink. My mind is empty; perceiving, concentrating.

This is the penultimate scene of an almost five hour show with no intermission, and must be the simplest bit of music theatre ever to be taken so seriously. But Einstein on the Beach is not a normal opera. It has no story, no plot and no protagonist. Director Robert Wilson comments: “In this work, it’s ok to get lost. And if you don’t let yourself go, you’ll sink or you’ll leave.” Why was I so moved by 5 hours of random, disconnected events? The answer seems to lie with the artists’ ideas and goals for this monumental gesamtkunstwerk, that still feels fresh nearly forty years after its conception.

Robert Wilson was born in Waco, a small town in Texas. He came to New York in 1963 to study architecture, beginning his artistic life with an interest in the modern classicist ballet of George Balanchine and the non-narrative dance experiments of Merce Cunningham. His education as an architect is apparent in the visual design throughout his work. For Wilson, the concepts of space and imagery are paramount, and were the starting points for Einstein on the Beach. Rather than beginning by exploring ideas about Albert Einstein, he first decided that the opera was to last 5 hours and would consist of four acts, interspersed with five shorter ‘knee plays’, and two dances. Einstein allows this approach of structure first, content second, because the opera does not tell a story: it brings to attention different ways of seeing. The idea for Einstein’s structure comes from painting, whereby space can be represented in roughly three distinct ways: portrait, still-life, and landscape.

The first knee play consists of two stenographers making calculations. One recites a poem; the other, random numbers. This and the other knee plays happen in front of the curtain, on a small part of the stage. The viewer focuses on one thing: a portrait.

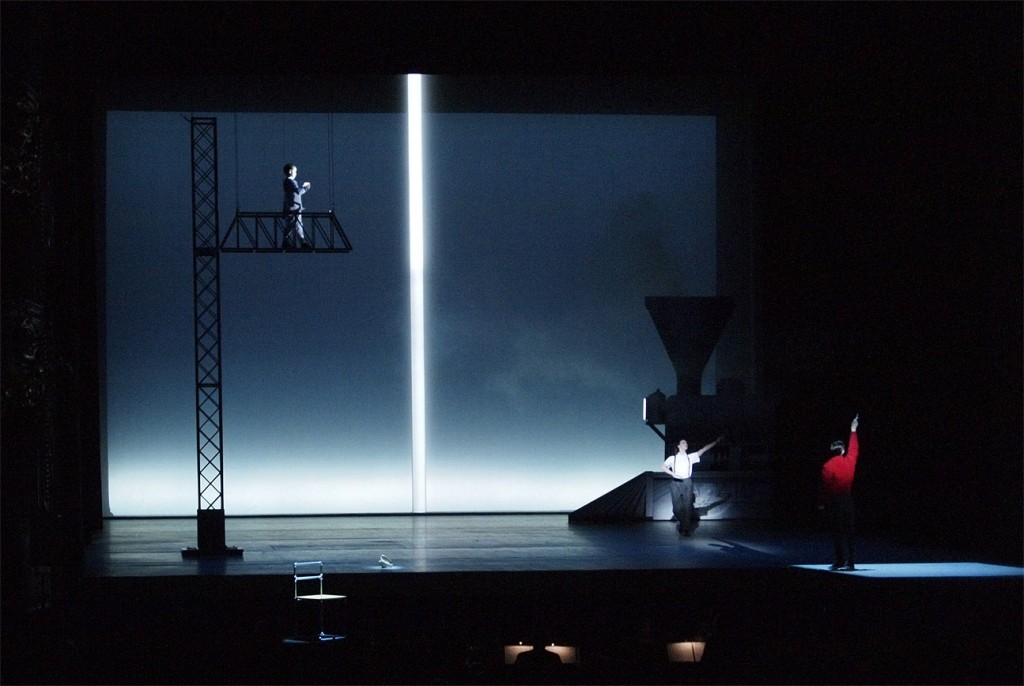

Act I, scene 1: a train pulls into a station, a dancer makes repetitive diagonals, a boy (the young Einstein?) on a crane holds a lit cube and at intervals throws a paper airplane, a man in red holding a pencil gestures in the air. As everything happens at the same time, and developments are incredibly slow – the train takes a good five minutes to completely enter the stage – the viewer can comfortably watch every visual element one by one. This is a painting with multiple elements that together form a composition: a still-life.

The dances are nothing like the scenes. The entire stage is cleared and the dancers use all the available space, in endless whirling circles like electrons around an invisible core. Only when watching the second dance did it occur to me to stop examining the single elements, and instead zoom out to see the whole landscape.

These different ways of using the space don’t make the events any easier to grasp, and none of the scenes seem connected. Yet what I did develop was an increased awareness of the need to keep seeing things in different ways, to appreciate the picture being painted. Far from providing any answers about what the work might mean, the process provokes ideas about how you see. That in itself is the point of the images. They provide elements that can be associated with Einstein, but most of all, they lead the viewer to question the very act of perception, to see the world onstage with wonder.

While Wilson’s use of space interrogates our ways of seeing, Glass’s music constantly questions our expectations of music. A child genius, obtaining a degree in mathematics at the age of eighteen, Glass himself remarks that his student compositions were not particularly interesting until he worked with Ravi Shankar in Paris. Shankar, the guru of Indian sitar who had a profound effect on the development of The Beatles, impressed Glass with his polyrhythmic music. Whereas his contemporary Steve Reich explored minimal music as slowly developing soundscapes, Philip Glass broke with Western tradition by pushing rhythmical changes to the forefront of his compositions. In Einstein’s score, tempo and rhythm are constantly changing and 5 or 7-beat bars often feature.

Just as in Wilson’s theatre, where the viewer has to let go of the deeply grounded expectation of narrative, Glass’ listener has to let go of the deeply rooted expectation of constant rhythm. The composer points out the difference: “Traditional theatre is about the identification of the audience with the hero. It depends on a sort of confusion of mind: you have to get yourself mixed up with Hamlet. Our kind of theatre does not operate on that mechanism. I remember working on a piece called Comédie, by Beckett. It’s a play about three people who are somehow speaking from the afterlife. I saw it many times. And what I noticed is that the emotional high of the evening would happen every night in a different place. In a play of Shakespeare, it should happen every night in the same place. Every night, when I watched Comédie, the epiphany of the play happened in a different place. And I finally came to the conclusion, what was really happening was that the mechanism had not to do with my getting involved, but with being separated from the piece. Our theatre depends on that.”

The text is, if possible, even more counterintuitive. Essential for narrative in traditional theatre, in Einstein language serves as a further instrument of separation. The text consists of a few poems mostly written by Christopher Knowles, an autistic child whom Wilson discovered at age 13. It features sentences such as: “Mr Bojangles if you see any of those baggy pants it was huge chuck the hills. If you know it was a violin to be answer the telephone and if anyone asks you please it was trees it it it is like that Mr Bojangles, Mr Bojangles, I reach you.” Throughout the performance these lines are spoken with an artificial intonation which is both non-dynamic and yet equally not robotic, removing any possible clue to interpretation.

To make matters worse, a few sets of phrases are endlessly repeated, but eventually these words are heard so often that they produce a special, unexpected result: dissociation, between the words and their usual meanings. Pathological dissociation is connected with psychological disorders, but the milder form can be imagined as follows: if someone concentrates on hearing ‘table’ over and over again, at some point the word loses its meaning and becomes a mere sound. It is then possible to give ‘table’ an emotional charge, for instance, if repeated while crying, ‘table’ can acquire the emotional meaning of sorrow. This is exactly the method that Einstein makes use of. Texts are repeated over and over again, until the listener realises that the phrases have renounced their semantic meanings. This unnerving experience, combined with the strange music and images, destabilizes ideas of language, as well as those of sight and rhythm.

Through image, music and text, underpinned by the concentrated boredom caused by the production’s glacial pace, Einstein achieves a double separation. On a specific level, the expectations surrounding each element of the production are shattered and make the viewer truly notice them. The second separation happens through the combination of image, music, and text, in a such a way that the endless bombardment of the mind with seemingly never-ending, slowly developing patterns makes one question everything, before letting go of expectations. The resultant experience is like a hypnotic dream, in which a bar of white light, slowly lifted up, can be seen for what it is: simply beautiful.

The methods that Einstein on the Beach uses are not unique. Glass and Wilson were greatly influenced by playwrights, and by artists like Sol LeWitt, who conceived of art not as a mechanism to tell a story, but rather as an instrument to ask questions about the way we see the world. Einstein is unique, however, because it is the first and only work to successfully apply these methods to the relatively conservative genre of opera.

Wilson explains: “If you take a baroque candelabra [sic], and put it on a baroque table, that’s one thing. But if you take a baroque candelabra, and put it on a giant rock, that’s something else. And maybe it’s easier to see the candelabra when it’s on a rock than when it’s on the table. In this theatre, it is about that. It is about: ‘How do I see?’ and ‘How do I hear?’”

For me the best part of the opera happened once I got past these questions and accepted what happened without any expectations. I watched the last two hours completely focussed on the aesthetic value of a white bar of light and heard a saxophone like never before; I was moved by a love story as if I was hearing one for the very first time. It is this achievement, allowing one to see known things with new eyes, that signifies a timeless work of art.

CC-licensed images by roberto zava – step