The future of happiness

by Ole Andreassen | October 29, 2012

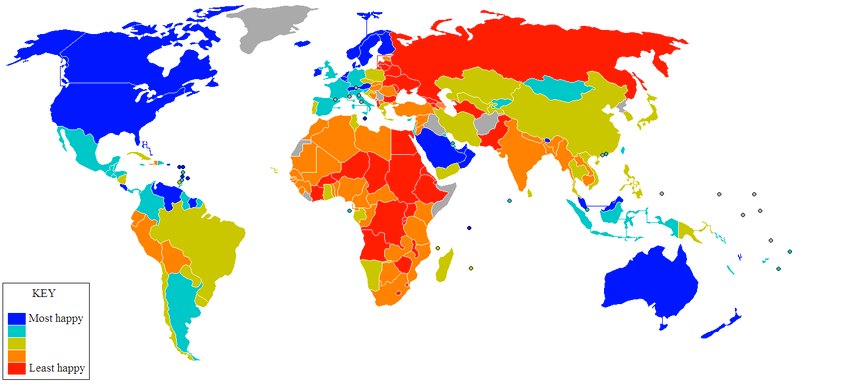

Are you happy? Is the person sitting next to you, if there is any such, happy? I don’t know; perhaps even you don’t know. I do however feel confident telling you that, whenever you are reading this copy of ISIS, right now Anders Sandberg is happy. He does various research for our University’s Future of Humanity Institute, and his is the sort of enthusiasm which should be accompanied by a bow tie (it isn’t). Anders, a Swede, says that half his family is remarkably dolorous, even by Scandinavian standards; the other half abnormally cheerful, even by non-Scandinavian standards. He belongs to the latter, and is therefore well suited to talk about happiness.

A good starting point is demarcating ‘narrow’ happiness. An example of narrow happiness would be the pleasure afforded by a tub of ice cream. You could be leading an unhappy life and still find much joy in your tubs of ice cream. Narrow happiness is just another psychological state, conceptually distinct from happiness understood as deep existential fulfilment and contentment. Anders has done a lot of research in neuroscience and modelling the human brain, and, unlike deep existential fulfilment, narrow happiness can be both modelled and formalised. He uses the analogy of the Roomba. The Roomba has a purpose; to clean your room. We can program it so that it is rewarded the more dust it sucks up, and punished the more objects it bumps into. It should then be able to adapt in a way that maximizes rewards and minimizes punishments. In roughly the same way certain parts of the brain have associated functions, ‘lighting up’ whenever the associated function is achieved: this lighting up would be, for practical purposes, a reward which, depending on your metaphysical stance, either constitutes the experience of narrow happiness or accompanies it. Having formalised this system of narrow happiness, we might want to find shortcuts. In our analogy the Roomba might find that the best way of maximizing rewards would be to eject a trail of dust behind itself, and then go around in circles: it would then be constantly sucking up dust!

I suggest 4chan as a human example of such shortcuts, and Anders, a forty year-old respected academic, agrees wholeheartedly. The following description makes the site sound more innocuous than it is: an internet community where anonymous users upload photos. If we want to be aroused, 4chan has sexy photos for us. Or maybe internet porn is getting old. In that case our brain has areas which ‘light up’ when, say, taking care of helpless beings in the community; 4chan will provide unbelievably cute kittens. Spending your time on such sites – and let’s be honest, we all do – is a bit like the Roomba going in a circle, sucking up the same dust repeatedly. That’s not a good thing; it is known that ‘thank you, 4chan, for making my life happier!’ will never be said in earnest.

Anders provides an explanation that’s more than marginally creepy. The reward of certain brain areas lighting up is something we inescapably want, but it is not something we necessarily like. Brain activity associated with liking something can be neurologically distinguished from brain activity associated with wanting something: while we might want to look at cuddly cats to the point of compulsion, there is no neurological reason for us liking this experience of ‘cheating’ our brain. Narrow happiness might well morph into squalid addiction, where we have to keep on doing it, even though we don’t really like it. And even if not, we will encounter what is known as a ceiling-effect: However enjoyable an activity is, the more you do it the smaller the reward gets, until you reach the asymptotical point where further spoonfuls of ice cream will be at best an inconvenience and at worst nauseating. Anders assures me this common sense truth has a firm neurological basis.

Here comes the sad clincher; truly existential contentment is so complex that it involves most of the brain, not just some isolated centres. And once we look holistically at the jelly stuff in our noggin, the Roomba analogy breaks down. Cheating our way to happiness, whether in the deep or the narrow sense, just isn’t that easy. Some of us might be stuck being morose, I tentatively conclude. Anders agrees, with the caveat that we have so far only looked at the current state of the brain. In principle we could just build pleasure receptors and plug them into our biological hardware, carrying large rucksacks of joy around with us. And on that (happy?) note I leave the Future of Humanity Institute.