Lost Tribes

Draped in purple and orange finery, men in bowler hats solemnly follow the Union Jack to the sound of flutes, penny whistles and drums. It is 12 July and the Orange Order are marching in commemoration of William III’s victory over James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Beside the men march the youth brigade, dressed in royal blue paramilitary outfits. These uniforms have long ceased to be an effective PR campaign for nationalists, and watching them float through Liverpool city centre is fucking weird.

Growing up in Liverpool I saw the dominance of faith schools that gave the Catholic and Protestant churches an unnerving hold on the minds of children.

The Orangemen, the King Billys, the Proddies, the Huns. Whatever you choose to call them, these marchers are the relics of an ancient conflict – the bitter and bloody antagonism between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland. To this day the 17th-century migration of Protestant Scots and English to Catholic Ulster has entrenched the two sects’ descendants in a miserable conflict. The shadow of this dark period of British and Irish history is cast beyond Ulster, over the centres of Irish immigration on mainland Britain. In Liverpool and Glasgow, just as in Ulster, religion and politics were once inextricable, as Catholic ‘republicans’ support, and Protestant ‘unionists’ swear against, the unification of Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

Growing up in Liverpool I saw the dominance of faith schools that gave the Catholic and Protestant churches an unnerving hold on the minds of children. My own mixed heritage condemned me to straddle the sectarian rift – embracing atheism was the only sensible choice. For me, all that these institutions offered were strange and incomprehensible rituals where one took equally strange and incomprehensible oaths. And the truth is, I may not have been alone in feeling that way. In the Liverpool of today such traditions are really nothing more than the husk of the once vicious sectarian strife. Marches like the one above are still relatively commonplace, but they represent nothing more than dutiful maintenance of tradition: the old hatred and spitting vitriol is dead. While the visual spectacle of something like an Orange Order parade is powerful, its ability to dominate the thoughts and identities of young men has long faded away.

Image: Gerry Popplestone

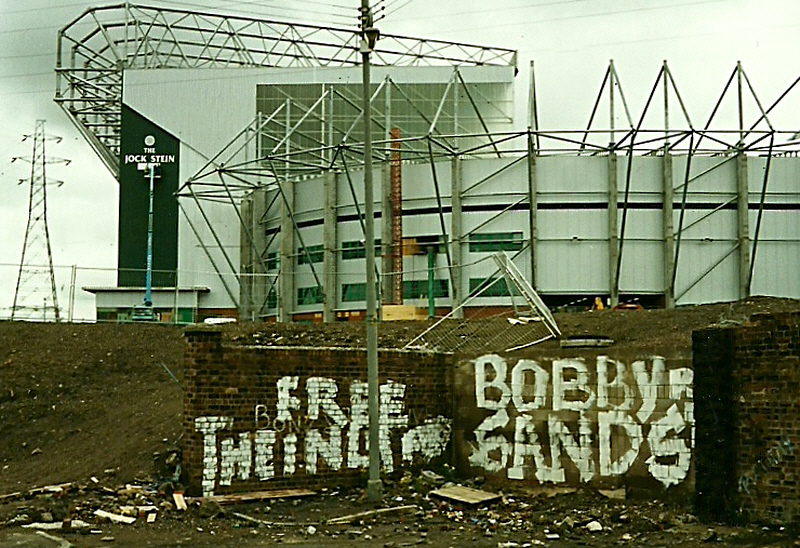

Image: Gerry Popplestone

Billy Owens, the grand master of the Liverpool Orange Lodge, bears very few resemblances to Northern Ireland’s tub-thumping unionist Ian Paisley. There is no trace in Owens’s voice of the vitriol that is so often used to caricature the uncompromising Orangemen. He sounds almost meditative about the Orange Lodge today: “Some people are bigots, obviously, on both sides. But in Liverpool that kind of confrontation has gone. We are at peace with each other.” He’s right. The violence and the venom that once plagued the Liverpool slums has all but evaporated. The chaotic tenements of North Liverpool have been brutally dissected by city planners. Generations of Scousers moved from the decaying apartments sprawled out on either side of Scotland Road and settled into new council estates in Kirkby, Speke and Norris Green. As these tenements crumbled, the streets ceased to be defined by allegiance to King or Pope. New badges of identity sprung up, based not on religion but on football and the city.

Jake Roney, director of the Liverpool Irish Festival, was an eyewitness to this transformation. “I remember seeing Orange marches all over the city in the 1970s. That’s pretty well faded away. I think the main thing is that the traditional communities were broken up in the slum clearances. Just as the Catholics of the Scotland Road area poured into Kirkby and places like that, the same thing happened to the hard-line Protestants. People have just been scattered to the wind.” Scotland Road once consisted of row upon row of packed slums squeezed tightly between the hills and the docks. This area had the highest density of pubs in the country, and elected an Irish nationalist MP for over 40 years. Today, it resembles any other post-industrial wasteland. All but one of the 200 pubs have gone and the rows of crumbling houses have been demolished to make way for empty fields of rubble and glass. Of course, the slums had to go. But the wrecking ball tore apart communities along with the rotting bricks and mortar.

Was this a ruthless solution to a difficult problem? Roney doesn’t seem to think so. “Obviously it wasn’t on purpose but that’s just the way it worked out. There’s still residual communities, Anfield Road still sees marches every now and again, but it’s just narrowed down to the football rivalry and not much more.” Despite these mass movements of inner-city communities following the slum clearances, most spectators would probably agree that Liverpool is a better place for its loss of the old sectarian feuds.

Tensions still run high in Glasgow and the violence remains an uncomfortable blot upon Scottish identity and culture.

Glasgow, on the other hand, continues to produce a grim spectacle of religious hatred. Tensions still run high here and the violence remains an uncomfortable blot upon Scottish identity and culture. Specifically, the sporting rivalry between Rangers and Celtic has become wrapped up in the ethno-religious conflict, to the extent that each clash between the two is treated as a re-enactment of the Battle of the Boyne. Rangers fans clad in royal blue brandish Union Jacks and St Andrew’s Crosses, separated from their ancestral enemy by a line of police. Amongst the Celtic crowd there is no sight of the Union Jack – the so-called ‘butcher’s apron’ – but instead the Irish tricolour, rising above a sea of green and white. The rows of policemen are a trembling bulwark against half a millennium of religious hatred. Words dismissing this as a souped-up football rivalry ring hollow amid the recent mailing of a parcel bomb to Celtic manager Neil Lennon and the Glasgow-based Irish republican group Cairde na hÉireann. ‘Ninety-minute bigots’ do undoubtedly exist here, but it is certain that the violence that accompanies the Old Firm rivalry is far more than political theatre. Sectarianism in Scotland is something very real and very divisive, particularly where football is involved.

The anti-sectarian charity Nil By Mouth was set up following the murder of young Celtic fan Mark Scott in 1995. The charity is committed to exorcising the spectre of sectarianism that still haunts Glasgow football. Ryan Taylor, a spokesperson for Nil By Mouth, stresses the abnormality of Glasgow’s football violence: “While most cities have rivalries between local teams that spill into violence, the intensity between Rangers and Celtic sets Glasgow apart. Rather than violent behaviour cropping up from spontaneous exchange, incidents are very often the result of deep-rooted religious and associated tribal tensions mixed with excessive alcohol consumption.”

Image: Jon Smith

Image: Jon Smith

As vicious as the hooliganism is, the strife in Glasgow is not all that pervasive. For all the violence between Celtic and Rangers, there have been no tragedies on the scale of Northern Ireland’s Omagh bombings. Aberdeen University academic Steve Bruce asserts that the sectarian rift in Glasgow is nothing near the same magnitude as it is Northern Ireland, where the highly ghettoised housing areas create a physical divide between working-class Catholics and Protestants. A 2001 survey conducted for the Glasgow City Council found that over half of married Catholics were married to non-Catholics. He compares this to the figure of just 6% for Northern Ireland.

The toughest problem facing the police and sectarian charities such as Nil By Mouth is determining to what extent cultural expression is legitimate. Can the singing of chants like ‘The Famine Song’, with its chorus “the famine is over / why don’t you go home?”, really be justified as a piece of heritage? The answer is shaping up to an unequivocal no, and Celtic and Rangers have sought to distance themselves from such songs. But how far can this curtailing of culture go? No one would strip the Hibernian green from Celtic, nor the Royal blue from Rangers. Nonetheless, it is certainly this poisonous marriage of the Old Firm clubs with the politics of Northern Ireland that exacerbates and perpetuates the problem of sectarianism in the mainland. In truth, the most powerful way to supress violent sectarianism is the destruction of communities, the Liverpool slum clearances that are still so prominent in Scouse folklore. This is how the old tribes and the old violence are removed. This is not the answer. As the juggernaut of secularisation unrelentingly envelops Western Europe, there are certain pockets that continue to act out old conflicts, old rivalries and old hatred.