Maybe I’m an anti-intellectual

by Anna Black | June 22, 2024

A year ago, a friend from home visiting Oxford took a deep breath after my new friends left the room. She said “you all speak really fast.” That “I’m on the last thing, and you’re onto the next. It’s all going over my head.” I was embarrassed. I realised only later that the art, here, is not only quick-wittedness, but also in not saying what you mean. In a parallel preoccupation with finding depth where it lacks, intellectualising the mundane. A disciplined showmanship of self-awareness; a banter that avoids earnestly confronting the notion that we might just be ridiculous. It’s not about who you know but what you know, what you react to, where in a conversation you subtly weave in a reference to being a Londoner, an inside joke the Oxford Union secretariat share, or what Purcell’s magnum opus was. What comes of it is a kind of quiet, passive exclusion, a social stratification between Oxford and somewhere normal.

It is of course, one thing to have the (forgivable) privilege to interrogate the world whilst others are given only their direct and undeniable experiences to work with. It is another, to have that privilege and use it only for discourse –self-contained, exclusionary, virtue-signalling, backhanded, ironic, exclusively drunken. Don’t think too far back, you can remember that high of a quality conversation, the serotonin of two people relating to a third coyly flagged thing. Quietly weaving a web of succinct ad libs about Greek myth, the banality of religion, or how power is discourse and is reinforced daily through imitations of a class-based nature (guilty). You learn to roll your own cigarettes, you wait to be introduced to the exactly right people, you pick up only mannerisms that signal disaffection. You wonder your friends from home would recognise you.

Like all things, this quickly becomes political. This week I spoke to a tutor who said that in tutorials, she wondered whether her students would “ever put their bodies on the line.” A day earlier, a friend went on a date with a Politics student who said they “didn’t know enough about Gaza” to decide. These anecdotes are disturbing because it is Oxford students who have access to the resources to understand the political world, who study it, and study in a place soaked to the bone in it. To study around politics is what I am interested in. It is not about ignorance: triggered often by misinformation, necessity, or political alienation. It is rather the ability to ritually forget that we are all obligated to do things. The word ‘apolitical’ has often been applied to mean people who say they have no interest in politics. In Oxford I think it more applies to people who are interested, but without being vested, which I see as the core of politics.)

Too many times in Oxford I have the displeasure of speaking with an Oxford species who can banter, defend, critique, sober, unveil, play and play and play the devil’s advocate (unto climax), but who cannot for the life of them deviate from a brand of hesitance. This person aptly will cringe at the suggestion they are apolitical (perhaps they are not) and is consistently an expert at infantilising and scorning the extreme. He is vigilant day and night about real concerns like bias, subjectivity, exaggeration and inaccuracy. He was, after all, encouraged to develop a distaste for these things, in his interview. (Now, life is just one big tutorial.) This person is not unwittingly or apologetically apolitical, but informed and apolitical. The irony is that this is deeply felt by the person to be some mission towards realness. But this is perverted, because his behaviour is the direct outcome of a scarcity of realness, a scarcity that results in an inability to identify the real. This-is-probably-not-as-bad-as-you-think, he would say to the real, if it slapped him in the face. You feel his back, and something is missing.

The indecisive feign humility and the humility masks fear: of ostracism, of impoliteness, of being wrong in the end. What is the end? Who will dictate when something stops being a joke and starts being real? Which authority that proclaims ‘genocide, for sure’ will you believe? When will it be imminent that you should believe in anything at all?

There is, after all, something truly gratuitous about the search for objectivity – it does not require any experience. Apparently, in “Oxford,” anyone can be an intellectual. All it requires is the insatiable desire to consume, and an allergy to anything brash. All it requires is a neat ability to take the Self out of the equation. You should relate to me, and not the flip way round – god forbid I have to roll around in the swine of difference, subjectivity, and worst of all, the un-aestheticisable. The bird’s eye is a convenient vantage point for those already at the top.

There are related thoughts I don’t want to have, like: can going to private school be forgiven by a preoccupation with literary politics? Maybe this is a problem academia also has to reckon with, at least when it is also responsible for social norms. Alas, the aesthetic is rarely outside the mating region: missing at a poorly attended protest, or a local organisers’ meeting with no young people. Young people wake up in droves for May Day choirs, to beat tradition like a dead horse, and protests on the same day are sparsely populated by young people, now fast asleep. What results from hedonistic lack of conviction that the adolescent intelligentsia possess, is immeasurable. It involves tumble weeding into Consulting, anxieties about finding Oxford-adjacent friends after uni, a distaste for vandalised art and direct action… But maybe that’s too harsh, and the overlap with politics exists.

In the Just Stop Oil laptop sticker? “ACAB” scrawled on ski lifts? In an increasingly androgenous closet, or the decision to cut off the problematic male friend? Those who do talk about politics place so many degrees of separation between them and their subject that it could be the weather. We accessorise politics not only when we re-share a post, but also when we decide to self-censor, afraid that bringing the news up might bring the mood down. One might wonder what the crime is. Surely our habits are taught, curated by a limited exposure, a British middle class, or even being gatekept from other types of coolness in a GCSE classroom?

I also fear conflating reference-culture with some distinct phenomenon of Britishness – the stiff upper lip, perhaps. The thought that my Indian expatriate parents, despite English being their first language, could for the life of them not relate to my friends’ parents. But perhaps I don’t relate to my own parents anymore. This makes me hesitant to think it is just Britishness I take issue with. It is something learned, maybe whatever people mean when they say, “that’s so Oxford,” not realising what was and is Oxford diffuses everywhere. Higher education was seen by 18th century British aristocrats as valuable for imparting social graces (civility, polish), and imperial conduct. And those knowledges needed to engage in such graces, or furnish a Grand Tour of Europe, explain why someone without the spare time or sensibility (money and privilege) to read for pleasure and conversation, went to other universities. Sometimes I think we ought to be a more embarrassed of going here, in ways that exceed not wearing your Oxford puffer back home.

And there is a material legacy to this obsession with civility, its false equation with rationality. Balliol man Alfred Milner, justifying concentration camps in Boer, South Africa, with a righteous conviction that they would bring the natives to a “higher plane of civilisation.” He recruited and trained future administrators almost exclusively from Oxford and expressed that the group of graduates composing of “Milner’s Kindergarten,” would feature “a regular rumpus and a lot of talk about boys and Oxford and jobs and all that.” What else do we talk about? How much have our interests, and ways of speaking, changed? Hyde, the Earl of Clarendon, was University Chancellor. History professor Fletcher wrote history books (circulated by the University Press) calling African slaves “incapable of any serious improvement.” Such justifications for colonialism link explicitly to the ability to achieve what many in Oxford saw as a higher plane of consciousness – not simply the absence of “savagery” but the manicured self-conduct they emulated, glorified. More perpetrators of global violence have shared the costume of sub fusc than any other dress, a fact that a faculty member recently noted. It’s all gone and done, you might say. Yet we strive, subconsciously, to a class above. Yet, Sunak more than anything, in his distance from real people, emulates Oxford. And yet, still, we decide whether to be in solidarity, based on how “reasonable” protesters are. How many degrees of translation will it take for true coherency?

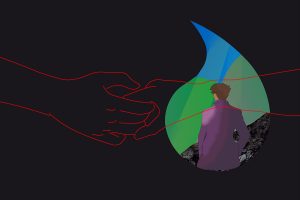

What can be helped is how jaded the Oxford-goer chooses to make each conversation, who they desire to relate to, and whether knowing and engaging can ever be the same as being in solidarity with.

I want to imagine a situation where an Oxford graduate must have a conversation about politics with someone who isn’t from Oxford, who that politics pertains to. I imagine the conversation as unsuccessful, the Oxford student operating at some different, dislodged tier of understanding, at a cognitive dissonance from the non-Oxford person. Interacting with awkwardness, aesthetic, (political) correctness, citations–anything but eye contact. Patricia Hill Collins puts, about “educated fools,” that “knowledge without wisdom is adequate for the powerful, but wisdom is essential to the survival of the subordinate.” The problem as it stands is not just that the privileged curate a vocabulary and convention only, they are privy to, but that the oppressed have different ways of knowing. The feminine ‘intuition’, the ‘crazy hunch’, are all examples of testimonial injustice: where things don’t count as knowledge because they don’t conform to hegemonic standards of what knowledge is. This is important to Oxford because of its insulation, its tendency to forget that it not only portrays reality but creates it. We assume that intuition isn’t a way of knowing things, that we cannot connect with people who have not interpreted the world like us. And ‘us’ might be student Tories, but it more often might be ‘anti-Union white queers’, and groups of friends composed entirely of English students.

Is it called bourgeois socialism? Isn’t the framing of a discourse, the obsession with impenetrable theory, the identical magazine subscriptions, itself the neat ordering that constructs a social class? I think Foucault says much about this, and this piece is an example of the very thing it opposes, in the very publication that platforms things it opposes. Perhaps my only justified appeal is that we begin reacting in ways not dissimilar to a friend recently catching me out at the end of some glib, trite remark architectured as something else: “what could you possibly mean by that?”∎

Words by Anna Black (Psuedonym). Image courtesy of Cameron Samuel Keys.