Rulers Without Robes

by Anna Couzens | April 16, 2024

The recent BBC drama Marie Antoinette is an uncomfortable series to watch. The combination of off-tune music, flaking powdered faces, and menacing whispers reveals the truth which lurks behind the beautiful Versailles backdrop: it is a cage, rather than a palace, for the 14-year-old Austrian princess. In one particularly disquieting scene, the future Louis XVI and his bride are undressed excruciatingly slowly in a bedroom full of people on their wedding night. The power dynamic is evident as Antoinette covers her breasts with her arms, shivering. To emphasise the couple’s powerlessness, the scene ends with the crowd of older courtiers throwing small paper balls into the bed: a twisted token of goodwill which quickly descends into a malicious free-for-all. The contrast between the echoing laughter of the courtiers and the young couple’s terror portrays Louis and his wife as helpless pawns in a system which they are too young and naive to understand.

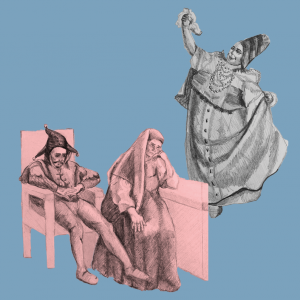

This presentation of French courtly ritual is misleading. The undressing of the king was not a humiliating affair; instead, it was a ceremony which reinforced his authority and enhanced his personal rule. In 1864, Louis XVI’s great-grandfather Louis XIV deliberately removed the distinction between his private bedchamber and public state rooms, blurring the boundary between his private and public self. The dressing and undressing of the king were turned into politicised courtly rituals: the levée and the coucher. By conducting his daily routine in the public eye, he merged two identities: his physical, human form, and his divinely appointed sovereignty.

It was a mark of great status to bear witness to this transformation, granted to only 40 of the most important courtiers at Versailles. To be allowed to remove the King’s clothes was the contemporary equivalent of being invited to spend Christmas at Sandringham. Aspiring, lesser aristocrats could only look on enviously, not even worthy to hold his dirty stockings. The ritual undressing of the French kings was not the degrading experience that is portrayed in Marie Antoinette; instead, it was a political performance which was central to the power of the French monarchy. The King’s body was a sacred entity, and by stripping away layers of clothing his courtiers could witness the true source of his authority: his human form, imbued with divine authority.

Of course, other political leaders throughout history have developed a similar style of personal rule to the French Bourbons. The personality cults of Lenin and Stalin immediately spring to mind. The populist idea of the ‘man on the street’ might suggest that these leaders invested their private identities with political power in a similar way to Louis XIV. Yet, in contrast to the wedding night scene in Marie Antoinette, The Death of Stalin depicts Stalin’s closest political allies as terrified to touch his body, even after he is dead. Propaganda may have depicted his private persona as accessible, but the ‘transition’ between his public and private identity was always manufactured and artificial.

In modern life, the idea that a political leader could be ceremonially stripped is inconceivable. Were Macron to be undressed by his aides in the Palais de l’Elysée, this would be degrading and could only damage his political career. Perhaps this is because modern attitudes to nudity are charged with shame and humiliation. In our society, being naked is a taboo associated with social ostracism. Nudity represents our most private self, and when we are naked, we become anxious that our public persona has been compromised.

This is particularly applicable to public figures whose identity is a carefully constructed image. The modern British royal family’s struggles with the press are a case in point: after a lengthy legal battle, the French magazine Closer was fined €100,000 for publishing photos of Kate Middleton sunbathing topless in Provence. The photos were deemed scandalous because they punctured the Duchess of Cambridge’s meticulously curated image of decorum and elegance. Seeing her naked reminds us that the royal family are ultimately like us—normal people with normal bodies and a private life which is unconnected to their public function.

There is something about being undressed by another person which makes the French courtly ritual entirely alien to a modern audience. Nudity, despite being rare in everyday life, is not always powerless and humiliating. We may giggle at the ‘bits’ included by ancient Greek sculptors—but portraying a naked male with a small phallus was once seen as the ultimate indication of purity, self-restraint, and morality. Life drawing remains an art form which celebrates the human form as an artistic object which is worthy of our attention and respect. Stripping could also be viewed as art: a choreographed routine in which the stripper reveals their nakedness on their own terms and gains sexual power and money in the process. Nudity is not, in itself, embarrassing or shameful. It is highly dependent on context. Given our perception of state leaders as dignified, professional figures, I imagine that a staged nude appearance during Rishi Sunak’s election campaign would provoke shock and uproar. Still, it would not necessarily make him an object of ridicule. If the nickname ‘Dishy Rishi’ is anything to go by, it might even help his position in the polls.

However, to extend this somewhat bizarre thought experiment, if Rishi was undressed by the members of his cabinet at the start of PMQs he would lose control over how and when he revealed his nudity. To be undressed by another person corrupts the barrier between private and public identity. The Prime Minister’s crisply ironed suits are the external complement to his public self: they represent the persona which he has chosen for the world to see. To observe the removal of these clothes would remind us that this persona is constructed, fragile, and fabricated.

At what point did attitudes towards undressing change? The ‘Chambre du Roi’ ceremony reflected the masculine, hereditary and deeply personal nature of the power commanded by the French monarchy. In a society where it was believed that the King was appointed by God, his physical body was the main theatre of political power. By ritualising the transition from their public to private persona, kings could demonstrate that there was no difference between their robed, ceremonial identity and their naked human form. The King was the embodiment of the state: he did not have to earn his power, as it was an intrinsic part of his personal identity.

Today, this idea no longer stands. Personal identity is not the source of public authority. Most leaders at least maintain the illusion that their mandate is granted by popular sovereignty rather than arbitrary birthright. The idea that Putin could legitimately have won 50% of the votes in the 2021 election may be even less credible than the notion that he was appointed by God, but it does demonstrate that even he recognises that his authority does not stem from his personal identity. A modern equivalent of the ‘Chambre du Roi’ ceremony would underscore the fact that political power rests on unstable foundations and can be assumed or abandoned as easily as a ceremonial robe.

Being stripped has a significance that goes beyond clothes. We speak of people being stripped of their rights, their dignity, or their freedom. The passive construction implies a helpless and involuntary loss. In our society, being physically undressed entails the same humiliation and disempowerment. This attitude is demonstrative of the careful watch we keep over the boundary between our public and personal identities. We may, on occasion, decide to strip for others and lay our most private selves bare. But to let another person undress us, taking control of the transition from our public to private persona, is a renunciation of power which is, in today’s world, unfathomable. ∎

Words by Anna Couzens. Art by Angelika Woodruff.