In Conversation with Adam Eli

by Antonio Perricone | January 29, 2019

In an article for Teen Vogue, Adam Eli describes Princess Diana as the perfect mix of princess, rebel, and activist. These lines read like his autobiography. I wanted to interview Adam Eli because there is no one else that I follow online whose coverage of issues that many of us care about is so infectious and accessible. In a time of shutdowns, cancel culture, political division and what feels like general catastrophe, Adam Eli’s voice is one of hope and an eagerness to work together for a better future. He also, frankly, seems funny and kind. He is in equal parts frank and guarded; during our conversation I noticed his uncanny ability to stop himself mid-sentence, self-censor and edit what he’s about to say. He manages to toe the line between telling his story and prioritising the message at large over his personal opinions. He is refreshingly positive, engaging and dedicated to what he does.

The following is a write up of the conversation I had with Queer Jewish activist, writer, social media firebrand and all-round role model Adam Eli, one dreary December evening. Some questions and answers have been edited for clarity.

AP: You started organising protests in high-school. Why did activism appeal to you as a teenager? How have you changed your approach in regard to your message as you’ve grown older?

AE: So, it started in high school. I grew up with a sense of social responsibility that, I think, came from my Jewish upbringing. I believe in inherited trauma, and so for a lot of my childhood we spoke about the holocaust, a lot, and so the idea of ‘never again’ was really prevalent. I was a freshman in high school and there was a protest about the genocide that was taking place in Darfur. I didn’t organise it though. It was huge. George Clooney spoke. No one at my school was talking about it and I thought it was bizarre because we were at a modern orthodox Jewish institution, many of our grandparents had gone through the Holocaust and a contemporary genocide was taking place. It felt like as Jewish people we have an obligation to show up for marginalized groups that are being persecuted in a similar way.

Then when I got older, I came out and I started to become really interested in LGBT history. I take a lot of my inspiration from ACT UP and that is when I sort of began organising around direct action. I’d say that my approach changed because I learned about activism, I learned how to be a queer activist. I learned it by sitting in Gays Against Guns meetings, I sat there learning until I had the tools to start my own group.

AP: That’s amazing. How do your Jewish and Queer identities inform how you view the world? People often see religion as a force for inhibiting sexuality, but I didn’t want to make any assumptions about your upbringing. How do you align the two?

AE: I really, really like that question because sometimes when I’m asked to talk about my intersectional identity, what people want to hear is “Oh I was gay, and I grew up in an orthodox home and community and it was so hard for me”. That is true. It was hard for me and it’s a story I feel is really important, but it’s been told before and what I want to talk about now is how I use my Jewish identity as a calling and a base for my queer activism.

Jewish people and queer people, I believe, are quite similar. We are both groups that have traditionally existed at the margins of society. We also tend to share an oppressor. Most notably we were both persecuted in the holocaust. In certain concentration camps, gays and Jews were marched right alongside one other. If there is a tendency for anti-Semitism, you can always find an uptake in homophobia and vice versa. Because I am Jewish, my ancestors know what it is like to be oppressed. Because I’m gay, I know what it’s like to be oppressed as my ancestors do. Therefore, I have a double obligation to stand up for other people being oppressed and silenced.

The biggest inspiration for starting a group and for my belief system “Queer people anywhere are responsible for queer people everywhere” comes from Dr Martin Luther King: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. It also comes from this line in the Talmud: “Kol Yisrael Arevim Zeh La Zeh/All the people of Israel are responsible for each other”. I literally just took that sentence – minus Jew plus queer. I use Judaism as a framework and a foundation for my activism.

In founding Voices4, a direct-action advocacy group, my biggest inspiration is ACT UP and Gays Against Guns. Another inspiration was the Soviet Jewry movement, which my mother was a very big part of. When Soviet Jews were being persecuted in the former Soviet Union, American Jews knew this and wanted to help. They would sometimes adopt a prisoner. Arefusenik, they called them. Your high school class, say, would be responsible for keeping that person’s name in the news. You’d show up to protests, carry a big placard with their name on it, raise money when it was needed and even donate some of your bar mitzvah money.

At Voices4, we do the same thing. For instance, there is a journalist called Ali Feruz. He was put in jail by the Russians. He was from Uzbekistan and was writing for the Novaya Gazeta, the oppositionist newspaper in Russia. They’re the ones who broke the story about Chechnya. When he was arrested, our group adopted Ali, the same way that the Soviet Jews adopted refusenik, and we did the same things. We helped protest, we raised money, we basically shouted his name until something happened and he was set free.

AP: Wow. It’s so nice to hear a story of direct action with a direct result.

AE: Yes. It wasn’t all us however. There was a global effort. One of the reasons he was set free was because of international pressure. There were people protesting all over the world, but we definitely held up the New York flag high. The answer to your question then, is that firstly, my Judaism is a foundation of my queerness and secondly, it’s the reason why I’m a queer activist. I use it as a tool to enrich my queer activism.

AP: It sounds like activism is familial, it’s an inherited trait.

AE: Yes, it is. The idea of ‘never again’ is familial too, both my parents, particularly my mum, are activists. My mum has an organisation called Mosaic of Westchester, which seeks to enrich the Jewish community through LGBT inclusion. They are over the moon about my activism.

AP: I just saw you were featured in the OUT100: 2018. What did that accolade mean to you and how do you intend to use that exposure?

AE: Of all the press and the articles I’ve written about, that accolade really meant a huge amount to me because I’ve always looked at that list. I remember not so long ago thinking that I wanted to be on it, but I didn’t even know in what capacity. I feel that in some ways it’s one of the highest honours you can get in the LGBT community. There are so many people on that list this year that I know and think of as my personal heroes. I was eager to continue using that platform to continue saying my message, “Queer people anywhere are responsible for queer people everywhere”, which is getting clearer every day. I think their portrait really showed that. It included my flag with the extra brown stripe which represents people of colour. It had my Voices4 pin, my kippa, my curly hair. I feel like it just really represented me. They saw me, represented me, and gave me a platform to continue talking about my message.

AP: In the light of recent events such as the Anti-Gay Purge in Chechnya and the anti-Semitic shooting in Pittsburgh, is there a right way to respond? In Oxford we recently had a vigil but where does one go next? What can those affected as well as allies do to help?

AE: First of all, I’m really glad to hear that you had a vigil, I think that’s really important. My big byline right after Orlando, which was the event which sort of kick-started my queer activism, was ‘Call your queer friends and tell them that you love them. Your random queer roommate from college? Call him”. And so, my big thing the day of the Pittsburgh attack was ‘Call your Jewish friends and tell them you love them”.

I think that having that vigil is important. I also think that attending the vigil, if you are not Jewish, is important. Posting from the vigil isjustas important as all of that because attending a vigil or protest is political and it is a privilege; a privilege that not everyone has. There might be someone at home, for whatever reason, maybe they are undocumented, maybe they are not out, that can’t go to a protest or a vigil so by posting It’s an active step of saying “hey I’m with you”. So, I think that posting is really meaningful. When it comes to the queer purges in Chechnya, when it comes to queer immigration, I am sure there are queer refugees, immigrants and asylum seekers within an eighteen-mile radius of you that could really really benefit from either a hug, or knowing that you’re there, or a hot meal, or just reaching out. I am sure that on your campus there are foreign exchange students, and some of them are queer, and they’re really struggling. When I was in college, I did an LGBT mentoring programme and we worked and hung out with a lot of kids from different countries that came to university and weren’t out to their families. I always say, go to your local LGBT centre and be like “Hi, my name is Antonio, I’m really good at cooking, I can speak two languages and I know how to weave baskets or whatever skill you have. How can I be of service?”. That presence definitely needs your support at a rally, or an invite to dinner, or a food drive or something… I’m sure of it.

AP: You mentioned in an email to me that you’re an anglophile and a Princess Diana devotee. How does Englishness affect your activism?

AE: Well, I love English culture. I love London and I love Englishness and I always have. My grandmother, who was an English Professor, brought me to London twice when I was really young, and it made a really big impression on me. My favourite writers are predominantly English and when I studied, I studied abroad in London at the London School of Economics for six months. When I did, I was like learning about the city, learning about its history, and I always had the sense of connection because, you know, London sacrificed so much in the face of evil. You know that famous Churchill quote… “We will fight them on the beaches”; they would not give up. They would not compromise, in any way. In that way the Jewish people and the people of England and the people of London and queer people, we shared a common enemy. An enemy that we beat at tremendous loss. So, when I was walking around the city, I would see that this lot was empty, or this building is new because the original collapsed in the Blitz. I could see the wreckage of the holocaust, in my own life, everywhere. It made me feel intrinsically at home and connected. Does that make sense?

AP: Yeah. That really makes sense.

AE: You know the holocaust plays such a large role in my life, so to have it play such a large role in this city, in the city where literally just getting on the tube, or like seeing that a building isn’t here anymore, you’re reminded of it. It made me feel at home because I feel like that was how I grew up. Whenever I go anywhere, I always look for the Princess Diana monument and the holocaust memorial.

AP: You’ve mentioned ACT UP. I recently saw the brilliant 120 BPM.

AE: You know that I’m like obsessed with that.

AP: I’m so glad! I am too. For my birthday my friend got me the Joey Smooth song from the film, Promised Land, on vinyl. When I first heard the lyrics, I thought it was a queer anthem… that film is constantly on the go for me.

AE: For me also.

AP: The film exposed me to a history that honestly might have passed me by. The Aids Crisis affected people of every walk of life, so it’s strange to me that I didn’t know about ACT UP. It can seem like a cultural blip in a way. At least that’s how I felt seeing 120 BPM and thinking “oh why am I not more familiar with these stories”. As kids we heard about MLK and the Civil Rights Movement but this whole period of struggle, in the last 30 years, just somehow wasn’t taught to me in school et cetera. Do you think there might be a generational indifference?

AE: I find it really interesting that you feel like the AIDS crisis is a cultural blip. How old are you?

AP: I’m 21.

AE: Ok so I’m 28, and so that’s really not such a big difference between us.

AP: Not at all.

AE: I live in New York City, which they call ground zero of the AIDS crisis and AIDS activism and so it plays a big role in my life. Even just geographically. I pass the AIDS memorial at least two or three times a week, Voices4 meets at the LGBT centre where ACT UP meets. I have friends that are living with HIV and I know a lot of AIDS activists.

AP: I lived in London and then we moved out of the city when I was a kid to a rural town in the countryside. So, my introduction to the AIDS crisis was reading about Robert Mapplethorpe in Patti Smith’s Just Kids or seeing Ed Harris’s performance in The Hours. It’s funny that we’ve pointed it out – maybe it’s a British thing, maybe we’re kind of tighter mouthed about things

AE: I would say it’s a distinctly Queer New York thing instead. The AIDS crisis is intrinsically woven into the queer culture and the queer history of New York City. In New York it is hard to miss the crisis even today. What I would say is, is that I fear… I fear that apathy is our worst enemy. My biggest hero ever is Elie Weisel, the holocaust survivor. His most famous quote, or second most famous quote, is “The opposite of love is not hate. It’s indifference”. The thing is, when it comes to queer people that are indifferent to their history – I am not mad at them. I don’t have much to say in regard to that. As an activist, it is not my job to activate people and move them into coming out and like inspire them to join us. Rather, I firmly believe that people care, want to show up, they just don’t always know how. So as a contemporary activist, it is my job to create tangible and easily accessible ways for people to show up and contribute, and then I use social media to promote them.

The truth is that there are so many people that want to give back to queer people in their community and abroad and there are so many people interested in queer history and passionate about where they come from that, for the time being, I’m going to focus on them. I don’t even have the time to give them all the attention and love and resources that they need, so when it comes to that sense of apathy, I’m not here to make someone un-apathetic. I’m here to work with the people that are already in it. Our plate is so full we have so much to do already (laughs).

AP: Of course. How can one person be expected to take on all apathy everywhere.

AE: Some people want to just live their lives and go to brunch and that is fine with me. Should they change their minds, they can look at my Instagram story and know exactly where to find me and will be welcomed with open arms. And if people need to take a two month break that’s ok too. I’m not going anywhere, I always say I’m the easiest person to contact – I’m like “Meet me here”!

AP: You talk about your own experiences with body-positivity and self-consciousness on social media a lot. I noticed with the recent Gucci show that you got your tummy out and were like ‘this is me’. It was really sweet.

AE: In front of like, 28 million people, that was so intense ahhh

AP: Right? Yet you continue to lend your image to fashion editorials. Is there a personal tension when you make those choices? Do you ever feel that you’re taking part in the corporate commodification of queer representation? In my head I kind of drew a comparison to how you viewed Diana and her relationship to the press. Taking media attention on your image and your body and identity in a way that, while somebody might be face-value just commodifying you, you can direct their energy elsewhere… to issues greater than yourself.

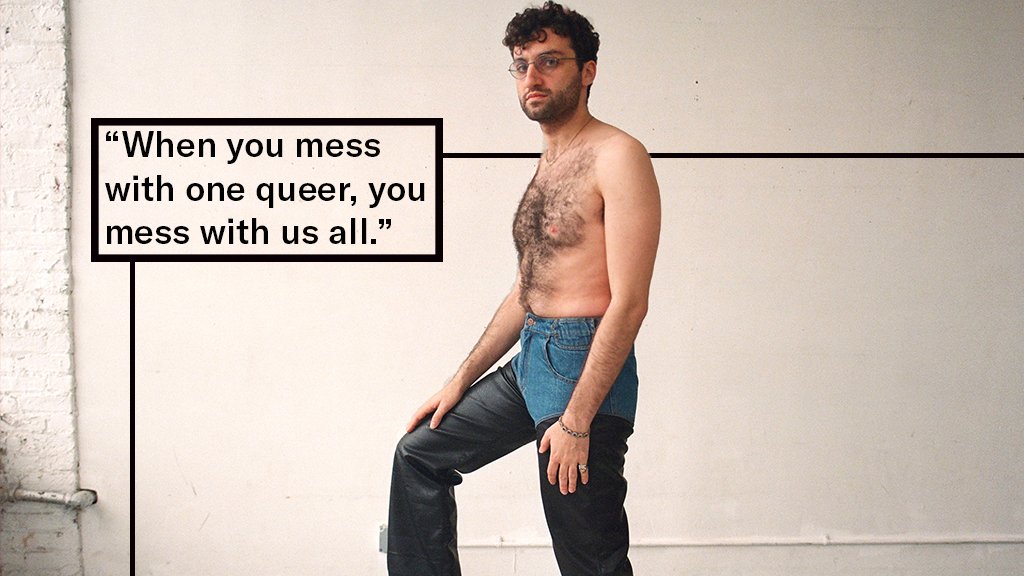

AE: First of all, thank you for this question and second of all, I firmly believe that you have to create the content that you wish to see in the world. And that is the reason why I post photos of my body I’m insecure about. If you say something loud enough and long enough sometimes it becomes true. I posted this photo of me from Gay Times UK and I hated that picture, I was so nervous it took me like three days to post.

AP: Which one?

AE: I’m like topless and I’m wearing my kippa, I have my foot up a little bit. It took me so long to post, I really don’t like that photo or how my body looks but I posted it because you have to create the content you wish to see in the world. So I can talk all that I want about the reason I think I feel this way about my body. Meaning that like… I’m not super ripped, I’m not super buff or like super skinny or bony.

AP: Twinky or Jockey essentially?

AE: Yeah. I’m not like a twink or a jock, I’m a human!

AP: You’re a person!

AE: I don’t see my body type anywhere. I never see it on social media. I certainly don’t see it in magazines or films. The only way that that’s going to change is if someone does it. I wore a crop top to London pride, I posted about it, and I hated it. But I hope that someone else saw me in a crop top and was like oh my god maybe I can do that too.

I also think that I’m sometimes given platforms that might not necessarily directly align with what I am fighting for. However, once given the platform and once I can get you to follow me, I’ll talk about whatever the hell I want. Once I have your attention, I can do whatever I want.

AP: Brilliant. In a them.us piece, titled Queeroes, you mention the repurposing of your first and middle names, Adam and Eli (notably both biblical), as your queer superhero name. It’s also your Instagram handle. Do you find yourself using social-media to self-fashion? What is your authentic self and how do you achieve it?

AE: I’m obsessed with this question. It’s amazing and I love it. I LOVE identity. I find power in identity. I find strength in identity. I identify very clearly on my Instagram as gay, Jewish and a New Yorker. Those are like my three biggies. Some people don’t like labels and need the space to just be themselves and I really respect that. However, I love identifying with those labels and I find a lot of power can come from it.

I think that social media is a great way to showcase and harness that power, especially if it makes someone feel good. And so, my social media rule is – if it’s not hopeful or a direct call to action? Don’t post it. You’ll never see something on my Instagram that’s just like AH TRUMP did this I’m. so. Angry.

After Pittsburgh, I didn’t just post ‘oh I’m really sad’. First, I posted “call your Jewish friends”, then “go to a vigil here” and then I posted a photo looking and acting super Jewish that day. I love my identities, I have always worn them on my sleeve, I wear my Jewish jewellery and I wear t-shirts that even express my Judaism like my fiddler on the roof t-shirt or a t-shirt that expresses my queerdom like a lady gaga shirt or even more explicitly a rainbow flag shirt. And Instagram or social media is just another way to wear your identity on your sleeve.

What you’re seeing on Instagram – is my authentic self. The only thing that I’m doing ever is exactly what I’m doing on Instagram, or I’m lying on my bed resting from doing that, or, having anxiety attacks. I’m more and more posting about the anxiety attacks on social media. I’m not hiding anything, it’s literally that and me in bed watching The Office. I’m starting to post more about me in bed watching the office and people love it.

AP: I love the mantra ‘if I’m gonna upload, it’s got to be positive and it’s got to be a call to action’. I think there’s a lot of power in that. It’s a nice way of reframing this constant narrative we have of social media as the end of the world: it’s going to kill us all and we’re all unhappy or whatever. So thank you.

AE: My key example is that one of the things ACT UP was best known for was their sophisticated use of the media. They would always teach people to talk through the media. Camcorders had just come out, so they would take camcorders, literally hand-held camcorders, to the actions, their protests, and they’d video what was happening, go home, put them on cassettes and then send them to news stations AND to their parents AND across the world to show what it was actually like on the front-lines of the AIDS crisis. Can you imagine what they could have done with Instagram live? Or Instagram stories?

There is no doubt in my mind that they would have been all over it. As queer people, and for anyone whose story has ever been marginalized or had their story taken away from them, we have to appreciate the power that is telling our own story without any filter. That is social media.

AP: That’s a radical way of looking at it. What do you attribute to the current political climate in America?

AE: I went to a play, Gloria: A Life, and Gloria Steinem gave a talk afterwards. She said that when a woman is in a domestic abuse situation, she is most dangerous or most vulnerable the moment before she leaves or decides to leave. The moment she’s leaving or the moments right afterwards. That’s when she’s most vulnerable. Does that make sense? ‘Cause she’s made the decision to leave, she’s upset her oppressor, and she might not have a plan. And so, Gloria Steinem believes, and I’m going to stick with her in saying that. We’re so close to so many good things that this is the backlash. This is the backlash, and the fear, this is the oppressor, who is losing and who is going to lose, acting out. And that is how I feel about that. But that woman, she’s going to get to the shelter, and so are we.

AP: From a more removed British perspective it feels easier to see Trump as a sign of failures in both sides of the political spectrum. Is there anything liberals can do better?

AE: Munroe Bergdorf, who I’m obsessed with, whom I love and who is literally a golden ray of light in the universe, She said something along the lines of “nobody is born woke, you’re asleep and then you get woken up”. So, if someone says something that is inappropriate, cancelling them is not the option, explaining why they are wrong can give someone the opportunity to apologise and working together after that is the right thing to do. I do not call people out on the internet and I hate cancel culture. I want everybody to be educated and move forward together as much as possible.

AP: Who are your role models?

AE: I have so many role models that I think are brilliant. My biggest inspiration is holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel. His quote that “There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest” is really important to me. My dear friend, Edouard Louis, you have to read his book The End of Eddy. My friend Brandon Wolf, who is a survivor of the pulse massacre and an incredible and relentless gun violence activist. Philip Pacardi, who is the new editor of OUT magazine who I believe will change the scope of queer media. Lastly, my fellow warriors at the Intersex Justice Project, where we’re fighting to end intersex surgery. I could go on for days…

AP: What are you reading at the moment?

AE: I just finished reading, literally last night, Edouard Louis’ Who Killed My Father and it is beyond brilliant. I’m also reading an advanced copy of Sissy by Jacob Tobia which is brilliant. I’m also reading Deray’s book, The Other Side of Freedom.

AP: Last question, what makes you excited about the future?

AE: Gen-Z. I love Gen-Z. The way that they’ve organised, particularly around the gun-violence movement has been incredible. I am so excited for them to lead and for us to watch. I’ve attended a high-school student organised gun-violence protest and I wish that I had brought a sign that said “Millenials <3 Gen-Z”. I just love it and I’m so excited. ∎

Words by Antonio Perricone. Illustrations by Antonio Perricone and Maia Webb Hayward. Photography by Hunter Abrams (@hunterabrams).