Kikokushijo: Returning Home

by Rita May | January 23, 2019

In Japanese there’s a word called kikokushijo. It’s a term that refers to Japanese children who have returned to their homeland after spending a period of their lives abroad. It’s a term that refers to people like us.

All of our early childhoods were spent in Tokyo, but we haven’t lived here in a long time. Ry and Keisuke both left Japan when they were nine years old. After moving back and forth between Japan and the U.S. several times, I left Tokyo for good when I was twelve.

We meet by the east entrance of Shinjuku Station on a cloudy afternoon. There are three of us: Ry, with his signature grey fringe and pierced ear; Keisuke, dressed in a leather jacket too light for the chilly day; and me, wearing a camera around my neck and insulated in a long black coat that is more blanket than garment. We make a strange trio in Tokyo.

“There you are, Ry.”

Keisuke and I have been waiting for several minutes, sending a string of impatient messages to Ry, whose brisk responses served no purpose other than to leave us more confused.

“Keisuke,” Ry says as he approaches us. The two boys clap each other on the back as I stand by with my hands shoved into my pockets. “You won’t believe what just happened to me. So, I was following the signs to get to higashi-guchi. when I got lost. And I was walking through Odakyu–you know, the department store–and then suddenly I was at a kaisatsu and I had to pay to get outside.”

“What? That makes no sense.”

“Happens to me every time I’m in Shinjuku.”

We mix English and Japanese with ease, forgetful of the fact that we are an oddity in Japan. The pinstriped businessmen, the fashionably dressed twenty-somethings staring at their phones, and the handful of blonde tourists milling about; none of them share this skill.

There is a difference between knowing Tokyo as a child and knowing it as someone teetering on the edge of adulthood. The city is far safer than you could ever expect a sprawling metropolis to be, but as with every place there are the good neighbourhoods and then there are the neighborhoods your parents tell you to avoid. We’ve seen our fair share of the high streets of Shibuya and Omotesando. We’ve come to Shinjuku for something else.

We head first to Kabukicho, the so-called ‘Sleepless Town’ of Tokyo. It’s a network of small streets tucked away behind the large shopping district of Shinjuku, the sort of place you don’t want to go alone at night. As we pass under a large archway displaying the words “Kabukicho Ichibangai”–Kabukicho, First Avenue–we spot a sign plastered to the wall: “If approached by a tout, notify the police immediately.”

“What, that’s illegal?” says Ry.

“Yeah, didn’t you know?” Keisuke responds.

“Then what are all these people doing?” Ry asks, gesturing to several dishevelled people along the street who are holding signs that beckon us to buy what they’re selling.

“Touting,” Keisuke and I reply in unison.

The name ‘Kabukicho’ literally means ‘Kabuki Town,’ but there isn’t a theatre in sight. The name originates from a failed attempt to build one here back in the 40’s, but the neighbourhood has nothing to do with that traditional art. Instead, what assaults our eyes now are signs advertising ‘massages’ and ‘free guides.’ We witness a sixty-year-old man leaving with a twenty-something woman from one of the stores lining the street. We share an uncomfortable laugh.

A lot of Tokyo is very clean and business-like: smooth grey buildings, swept streets, everyone dressed as if they were preparing to be in a photoshoot. It’s a very Japanese thing, this wanting to be neat, busy, punctual. I know parts of it have rubbed off on me. I sometimes find myself dressing up just to head to the supermarket or arriving to an event five minutes early even when I know everyone else will be ten minutes late. I have, however, lived somewhere other than Japan for half my life and at times, the rigidity of Japanese society feels suffocating. There are times when I want to embrace the messiness of being human instead of forcing a mask on myself day in and day out.

And so we go tiptoeing through the alleyways of Kabukicho. Some are narrower than others, some cleaner, some more pungent. What matters to us is that they are all different. In every corner of this little neighbourhood, there is something non-uniform that catches our eye. We turn our lenses to focus on Tokyo’s hidden treasure trove of garbage. We devour each scene.

Ry and Keisuke are both fully Japanese by blood. I am mixed: what you’d call a hafu in Japanese. The word is obviously derived from the English half, and in the last few decades has replaced a more outdated term, konketsuji. That word, literally translated, means “mixed blood child.” Although there is nothing outwardly offensive about that description, I’ve heard that the word used to be hurled as an insult at children like me.

Japan is a homogeneous society to the extreme. Out of the 540 children who attended my public elementary school, there were, at most, seven who were not fully Japanese. My classmates always treated me with an air of difference. They meant well, of course–it was curiosity that drove them and not hate. But their inability to accept me as one of their own was still palpable.

Even in Tokyo, the capital and by far the most diverse city in the country, few people are bilingual. Public signs often display broken English.

We head to Golden Gai next. It is a similar district to Kabukicho–narrow, winding paths lit by red lights at night. But the atmosphere feels slightly less illicit. We can hear lively music playing from one of the several small taverns lining each street. Keisuke takes one look at the neighbourhood and says, “This is so Showa.”

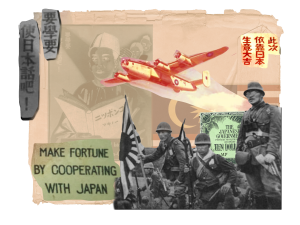

The Showa Period, or the period of time denoted by Emperor Hirohito’s rule, spans the 1920’s to the 1980’s. It is an important period in the making of modern Japan, not only because it includes significant events like World War II, but because it was a period of rapid westernisation. Showa gave birth to phenomena like the mobo and moga–short for ‘modern boy’ and ‘modern girl’–young people from the 1920’s who eschewed Japanese customs and tradition, opting to wear western clothes, marry outside of parental arrangements, and so on.

It’s been almost a century since mobo and moga walked down the streets of Tokyo. I think, in many ways, that kikokushijo have taken their place in modern Japanese society. Both are harbingers of foreign influence, at times disdained, at times admired, and always an object of curiosity.

It starts to drizzle while we are taking photos in Golden Gai, so we decide to take shelter in one of the eateries that line its streets. Before we enter, we have our usual debate.

“Do we speak English or do we speak Japanese?”

The establishment we have chosen has a sign in English out front. That might mean the owner is bilingual, but you can never be sure.

“Well, if we speak Japanese, we’re less likely to get ripped off. But if we speak English, they’re less likely to hassle us even if it turns out to be sketchy.”

Foreigners, or gaijin, are often viewed as intimidating in Japan.

“Plus, if we speak English it’s easier for us to get out of trouble,” adds Keisuke. “We can just pretend that we don’t understand what they’re saying.”

Ry is only half listening to our conversation. As soon as there is a pause in our speech, he pushes the door open and begins talking to the owner in Japanese.

“Excuse me, could we sit upstairs? Yes? Great, thanks.”

The three of us squeeze into the tiny space that is the first floor of the establishment. It consists of a small bar with a capacity of maybe six seats and nothing else. The owner is standing behind it, talking to a middleaged woman smoking a cigarette. Charred butts lying in her ashtray tell us that she has been here a while. I exchange a glance with her before heading upstairs.

Ry, Keisuke, and I all order a drink each and then chat about dinner plans. Two other friends of ours–Hayato and Jun, who are also kikokushijo–will be coming to join us shortly. I suggest a restaurant at a local department store, and my friends nod in agreement. We message the others.

The rain has ended by the time our plans are set. The three of us put on our temporarily discarded jackets and head downstairs once more. Ry begins chatting with the store owner in Japanese. Meanwhile, the chainsmoking woman turns to me and gestures at my backpack.

“Same,” she says in faltering English and points to her own bag sitting in the corner. It’s the same brand as mine. “Scottish bag.”

Maybe it is because I am offended that she treats me as gaijin, not even hafu, but I don’t bother to correct her by pointing out that the brand is Swedish. Before we leave, I exchange a few words with the owner about using the upstairs space as a gallery. I speak in Japanese, making eye contact with the woman one last time before going outside.

We head to one last district before dinner. Located on the opposite side of Shinjuku Station, Omoide Yokocho, literally translated as ‘Memory Lane,’ is a collection of small restaurants with a streetfood atmosphere. We arrive there just past 6pm when the cramped space is teeming with office workers who have come for a quick drink and snack before heading home. The smell of yakitori and beer fills the air.

Reading a menu should not be a difficult task for three literate eighteen-year-olds but Ry, Keisuke, and I find ourselves squinting at unfamiliar words.

The Japanese writing system relies on a set of two syllabaries, which are syllable-based alphabets, and one logography known as kanji, which consists of characters borrowed from the Chinese writing system. The syllabaries are easy enough to learn–with a finite set of fifty characters each, every six-year-old in the country can quickly master them at school. The logography, on the other hand, poses a problem. With tens of thousands of characters in use, it is an impossible task to learn them all. The Japanese school system teaches only what is useful, assigning a set of the most commonly used characters for children to learn at each year in school. By the time they graduate high school, they should be competent enough to navigate the world.

To anyone who has not experienced it, I do not know how to describe the difficulty of keeping up with kanji learning outside of the Japanese education system. Learning each character involves tedious memorisation of each stroke, pronunciation, and meaning associated with it. Finding the motivation for such a task on top of one’s regular schoolwork is difficult, to say the least.

Ry, Keisuke, and I have both done our best to continue our kanji education, but we are all aware that our competence falls short of the average Japanese person. Usually, our foreignness is a point of pride – we can boast about how we have seen so much of the world at such a young age, how we are more open-minded, how we know more than one language. And yet there are little moments, like when we scan a menu and cannot read the types of fish available to us, that reduce us to hunched shoulders and desperate Google searches with phones hidden underneath the table.

We call our friend Hayato the most Japanese one out of all of us because he is only in his third year of education outside of Japan. His home address has always read Tokyo. As expected, he arrives exactly on time. Our friend Jun, on the other hand, has been studying abroad for a decade. He arrives thirty minutes late.

I sit in the middle of the table. To my right, Keisuke and Hayato are speaking in Japanese; to my left, Ry and Jun converse in English. The hafusplits the table in half.

After dinner, we head to one last part of Shinjuku: Ni-Chome. This neighbourhood has had a reputation for sexual deviance dating back to the Edo Period. At one point a haven for sexual expression amidst a conservative society and at one point a hub of prostitution, it is now home to Tokyo’s largest LGBT+ community. Storefronts waving pride flags stand on nearly every corner and drag queens strut about the street at night.

I lead my companions to a club called Annex. A friend introduced it to me over the summer. According to him, the site was once home to a homophobic cult, but after its collapse, the gay community converted the headquarters into Annex. I have no way of confirming the tale, but as we walk in, I note crosses etched into the stone walls of the club.

The space is deserted on a Thursday night. The five of us sprawl out onto seats and watch multi-coloured lights dancing along the walls and floor. A fountain bubbles in the centre of the room, its waters glowing rainbow.

“Do we look gay?” Hayato asks at some point.

I shrug my shoulders.

Japan has held an ambivalent attitude towards the LGBT+ community for quite some time. Less discriminatory, more dismissive. Unlike many western nations, Japan does not have a history of religious persecution of homosexuality. Nonetheless, it lags behind in legal rights compared to nations like the U.K. because media outlets and educational institutions alike refuse to discuss the issues the community faces. When you grow up in a community whose core value is uniformity, the already difficult task of standing up and saying “I am different” becomes a near impossibility.

Whenever I go to Ni-Chome, I feel a strange sense of security. It is a place where being out of the ordinary is expected. It’s freeing. But again, it’s only a miniscule pocket of the city. A fact that makes me glad I spent my adolescence somewhere other than Tokyo.

The trains stop running in the city somewhere between midnight and 1am. If you want to be home before the morning light, you have to catch the last train back.

Three of us–Hayato, Jun, and I–have to head to Shinjuku San-Chome Station to catch our trains; the other two, Ry and Keisuke, are taking trains from Shinjuku Station. We part ways in front of the department store where we had dinner. Iron grates now guard the delicate glass storefronts and every door is shut tight, transforming the building from a welcoming place of commerce during the day to an intimidating fortress at night. I bid Ry and Keisuke goodnight before heading underground with Hayato and Jun.

A Japanese station at this hour of the night is surreal. In one corner, an office worker who stayed out too late crouches over a grate dry heaving. A group of sleepy station workers glance down at their watches. Someone wears clothes from a subculture you’ve never heard of. The entire place smells of vomit.

Hayato glances up at the train schedule and his eyes widen in surprise.

“Wow, it really is the last one.”

“It hasn’t been a good night unless you’re on the last train back.”

He nods in agreement.

Jun and I are on a different train from Hayato. Ours arrives first. In a daze, we wave Hayato goodbye and board.

“So,” Jun says once the train begins to move, “do you know any normal Japanese people? You know, people who have always lived here.”

I pause a moment before responding.

“No. I don’t really know any normal Japanese people. Not anymore, at least.”

Jun shrugs. Maybe he means it’s okay. Or it doesn’t matter. Or he is too tired to respond. The train rocks us back and forth as it travels along the track, my eyes closing a few times as we sway along with mechanical speed. It’s a cradle of sorts, carrying us all home for the night.

What’s a normal Japanese person anyway? I think to myself

Maybe there is no such thing.∎

Words by Rita May. Photography by Rita May, Ryuichi Otake, Keisuke Sano.