Japornography

by Alex Dudok de Wit | July 20, 2011

“Hentai girls can do anything! Real girls couldn’t begin to take what these girls do! 6 foot tentacles, 24 inch cocks, demons and aliens…”

When I was at university in Japan, I used to commute every day in a train packed with businessmen. The first time I looked over at the magazine that the suit sat next to me was reading, I was surprised to see a cartoon octopus penetrating a schoolgirl in every available orifice. By the second time I was used to it.

It’s wrong to assume that hentai porn – sexually explicit manga (comics), animation or videogames from Japan – only appeals to bedroom geeks and knife-wielding psychopaths. My fellow commuter was clearly not ashamed of reading it openly on the train, and with good reason: in Japan I’ve seen hentai on tables in cafés, shelves in HMVs, bookcases in hostels. In a country where manga accounts for a third of all published material, its pornographic subgenre is no dirty secret.

Most westerners would hold this up as sordid proof of Japan’s weirdness, but they’d be ignoring the genre’s increasing popularity here as well as at home. A Google search of the term ‘hentai’ (which, confusingly, isn’t even used in this sense by the Japanese themselves) turns up 178 million hits (twice as many as for ‘sushi’ or ‘samurai’). And there’s an expanding literature in which western scholars describe their experiences of hentai in curiously academic language (watching hentai films “is never a passive experience”, notes one cryptically).

I’ve seen hentai on tables in cafés, shelves in HMVs, bookcases in hostels

At the same time, hentai’s reputation is at an all-time low: its association with recent high-profile murders in Japan, and the controversy whipped up by extreme titles such as the videogame RapeLay (in which the player rapes girl after girl), have done little to boost its crossover appeal. So how to explain the genre’s enduring appeal in Japan without concluding that the Japanese are a bunch of latent perverts? And why are we even giving it the time of day over here?

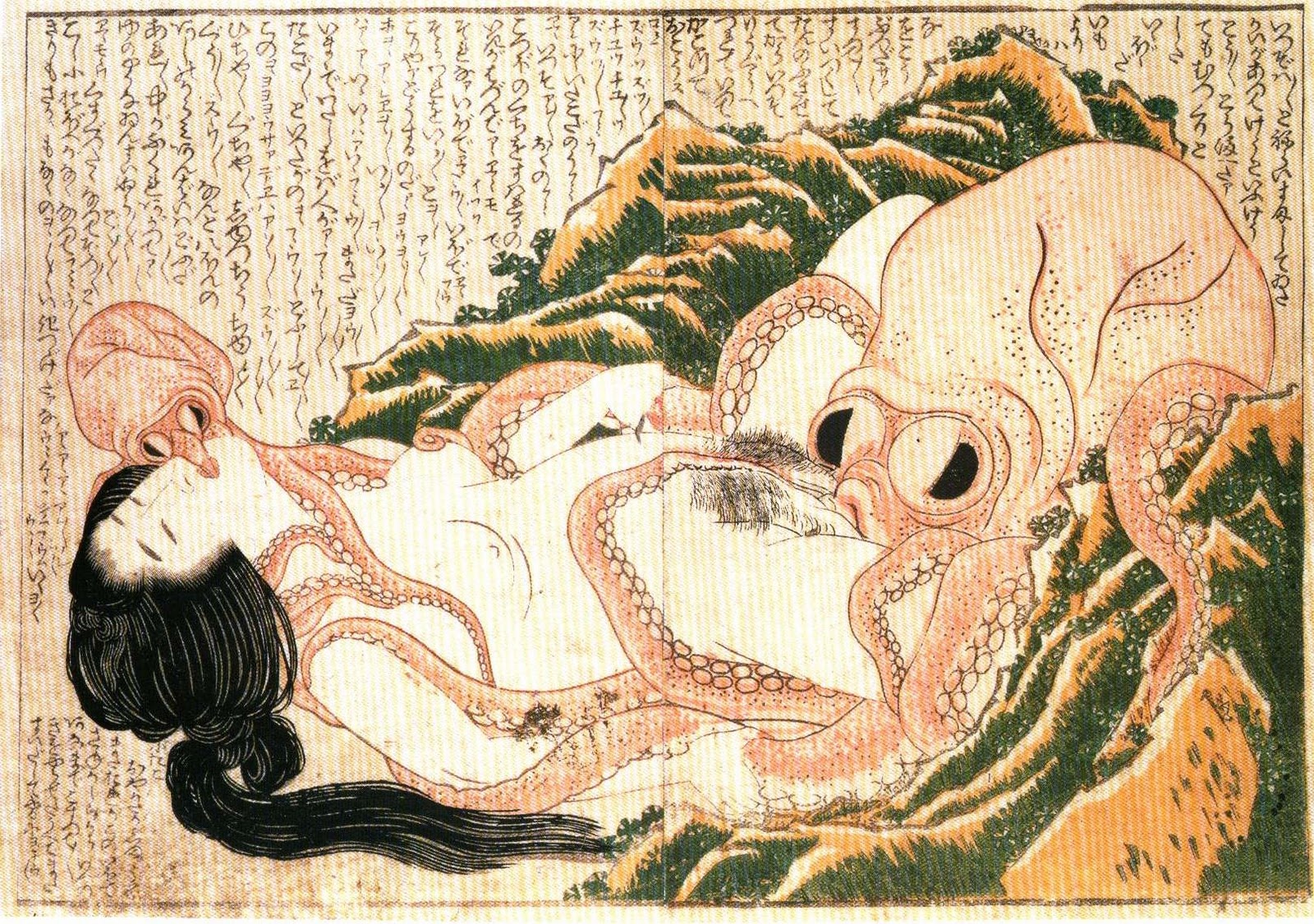

Hentai is characterised by its depiction of all manner of bizarre, grotesque sexual practices – the kind alluded to in the quote that opens this article (from American website Lil Miss Hentai). Those who like to think of premodern Japan as a rarified land of samurai and geisha may therefore be surprised to learn that most of hentai’s sexual deviances and fetishes can be seen in shunga, erotic prints that were popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The most famous shunga print, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife by Hokusai (of Great Wave fame), is below.

Shunga themselves are steeped in the traditions of Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion, for whose animist spirits sexuality is an innate part of life. Far from the models of chastity that a westerner might expect of deities, these spirits often use their supernatural powers to accomplish incredible sexual feats. I’m not suggesting that shunga and hentai are explicitly religious, but it seems that Shinto mythology – by sanctioning the treatment of sexuality in art and literature, and tying it to the supernatural – set a precedent for the situations depicted in these kinds of porn.

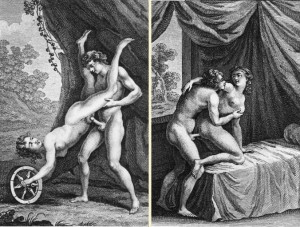

As Japanese society sought to modernise – read ‘westernise’ – from the mid-19th century onwards, pornographic novels and pictures came to be seen as ‘low’ arts and shunga production was curtailed. At the same time, Freud and the western sexologists began to be translated into Japanese, and it was in this context that the psychological term ‘hentai’ (meaning ‘perverse, warped’) was coined.

By the 20th century, the name ‘hentai’ was being applied to the lowbrow pornographic literature that was being churned out on the back of increasing literacy and an expanding press. Fuelled by the sexual revolution, in the postwar years Japanese erotica branched out into the nikutai bungaku (‘literature of the flesh’) novels, ‘pink films’ such as the infamous In the Realm of the Senses (if you’ve ever wanted to see a Japanese woman lay an egg, this film is your chance), and the first pornographic manga. In Japan, the word ‘hentai’ is still used to mean deviant sexual practices, but the Japanese don’t use it to refer to the genre as a whole, preferring the terms ero (‘erotic’), etchi (‘H’, which may well stand for ‘hentai’) or seijin manga (‘adult comics’). Those 178 million hits must mostly be our fault.

Hentai can be sophisticated or cheap, hardcore or softcore, sometimes misogynistic

Hentai today is a mixed bag of art sophisticated and cheap, hardcore and softcore, in places but not always misogynistic. It comprises a dizzying array of subcategories: yaoi (porn about young male relationships), lolicon (from ‘Lolita complex’ – the protagonists are little girls), omorashi (‘wetting’ – the characters are aroused by full bladders), and the self-explanatory ‘tentacle erotica’ to name but four. It’s not always legal: dōjinshi hentai features well-known pop culture icons in breach of copyright, while the status of lolicon regarding child pornography laws is unclear. But they proliferate on the web, where it’s hard to crack down.

It’s tempting to wonder what it is about hentai that its audience finds arousing. If the appeal of porn lies in its voyeuristic character, the way it presents viewers with a real sexual situation onto which they can easily project themselves, then what’s the point of porn that denies us this realism? This is where the academic studies come in, and opinions are varied, although there appears to be a vague consensus that “arousal is reached through a kind of sceptical suspension of disbelief”, in the words of Mariana Ortega-Brena. Anne Allison and many others have pointed out that the Japanese sex industry focuses on transporting the participants into an imaginary space free from the stress imposed by professional and familial responsibilities (which in Japan are severe) – hence the argument that the magical bathhouse in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away is a thinly veiled brothel. Hentai ties into this nicely.

One can argue the ethical advantages of hentai. It’s a safe outlet in which to give free rein to your more extreme fetishes. Real women (and men) aren’t compromised. If sexual information substitutes for sexual activity, the popularity of hentai may account for the late sexual maturation of Japanese adolescents (teen pregnancies are rare in Japan). Unfortunately these claims are undermined every time hentai features in a high-profile criminal case, which happens often. In the late 80s, for example, serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki murdered four little girls, one of whose blood he drank and hand he ate. A search of his bungalow turned up 5,763 videos, many of them hentai. Even more disturbingly, the relationship between hentai and murders sometimes goes the other way: when in 2004 an 11-year-old Japanese girl was murdered in her classroom by a schoolmate, it wasn’t long before hentai artists began incorporating the incident into their narratives.

Unsurprisingly, it’s these stories that get picked up by the western media, and so we end up expecting all hentai to glorify violence and rape. While there’s no denying that some hentai is nasty, the generalisation is again unfair. Unlike western porn, hentai draws on old traditions that unify sex with human life elegantly and enjoyably, and this approach is reflected in the medium’s treatment of sex. Timothy Perper and Martha Cornog note that far from condoning rape, hentai generally portrays it as a crime that “receives profound and often bloody retaliation and revenge… [Female sexuality] does not degrade a woman, but is connected instead to independence and autonomy.” We can again spot a precedent in Shinto, which features many strong-willed female deities, and appoints women to some of the most important priesthoods in the country.

Our mistake is to use our own western comics as a frame of reference when dealing with manga. Manga’s immediate ancestor is the ukiyo-e (woodblock) print; in 18th-century Tokyo these prints were mass-produced and considered lowbrow, but they’re now prized by art collectors. While a lot of it is instantly forgettable, the best manga (and so the best hentai) is artistically brilliant, and must be seen as part of a tradition of narrative picture art that stretches back beyond ukiyo-e to the 12th century. By contrast, western comics are a fairly recent invention; they’re aimed almost exclusively at kids, they’re in many places regulated by draconian censorship laws and they’re rarely taken seriously as art. So if we simply take manga as the Japanese equivalent of our own comics, it’s no wonder we’re appalled by the sexual content of hentai.

I think the fact of Japan’s exoticism clouds our judgment here. We in the west only get wind of the most excessive hentai, just as we so often hear of the latest extreme trend in Japanese fashion, or of yet another nerd collapsing in a Tokyo cybercafé after an 80-hour videogaming session. It’s too easy simply to see hentai as another piece in the puzzle, while turning a blind eye to the sexual issues at the heart of western societies, which to us are less strange and so more invisible. But the internet is giving us access to an ever-wider range of hentai, and the body of academic texts on the matter suggests that our bias is weakening. How long will it be before the guy next to you on the Oxford Tube is getting stuck into the latest issue of Squid Fetish?

Image: marcelinoportfolio