A Faustian Diagram

by Polina Ivanova | May 7, 2012

In 1539, the townspeople of Staufen im Briesgau discovered a body, locked in a room above the inn. Its neck was broken and its head was twisted right round – a sure sign of the devil taking a soul. It was the very same ‘Master Georgius Sabellicus, Faustus junior, fons necromanticorum, pyromanticus’ that Luther had labelled a “shithouse full of demons,” a man that history would transform into perhaps the most influential leitmotif of European literature. Faust’s decision to defy divine will for the sake of illicit knowledge, and his reward, death, have raised questions about the nature of man and his relationship with power that have never lost their relevancy.

“Look at those eyes”, filmmaker Sokurov remarked, watching archival footage of Stalin, “those are the eyes of a man who is absolutely free.” The achievement of this condition – freedom from ethical norms, from any conscience – is the question at the heart of a tetralogy of Sokurov’s films that has chronicled the lives of 20th century dictators. It is a series that, surprisingly, concludes with Faust, which received Venice’s Golden Lion this year. The nature of the wager Faust makes with the devil has evolved through time, each alteration relating to the character of the age, and Sokurov presents its most recent transformation to explain the source of the dictator’s freedom.

The original wager is infamous: 24 years of fulfilled desires and ambitions for the price of a soul, signed for in blood. It was born out of the dark confusion of the Reformation and its medieval heritage, beliefs thought unshakeable threatened and man no longer held at the centre of the universe. All that was reliable was the omnipresence of the devil and his occult paraphernalia – witches, alchemy, cosmology, Flamel. The wager, which sent Marlowe’s Faustus to a fiery hell, is a warning against an attitude of self-reliance in the face of God emerging in Renaissance thought.

The original wager is infamous: 24 years of fulfilled desires and ambitions for the price of a soul, signed for in blood. It was born out of the dark confusion of the Reformation and its medieval heritage, beliefs thought unshakeable threatened and man no longer held at the centre of the universe. All that was reliable was the omnipresence of the devil and his occult paraphernalia – witches, alchemy, cosmology, Flamel. The wager, which sent Marlowe’s Faustus to a fiery hell, is a warning against an attitude of self-reliance in the face of God emerging in Renaissance thought.

For Marlowe, Faust becomes Prometheus, attempting to emancipate man from the restraints imposed upon his knowledge, “To practice more than heavenly power permits.” Marlowe, himself a dissident and critic, trialled for blasphemy and accused of atheism, uses the legend of Faust to ask how far we would go to get rid of the limitations of being human. Who wouldn’t sell their soul for a flight through the heavens or for a Helen whose face so famously “launch’d a thousand ships”?

By Goethe’s time, the wager had changed. When God asks Mephistopheles, “Kennst du den Faust?“, Faust becomes a mere pawn in a higher process. Though man, by his nature, is still a “grasshopper,” whose desire for power and knowledge means he “pokes his nose in all the filth he finds,” he is no longer required to sell his soul to get it. By the the Enlightenment, Mephistopheles is no longer an evil tempter and seducer – he is the spirit of negation, permitted by God due to his ability to enlighten man with his critical nature and cynical nihilism.

“Throw off your limitations, throw away your conscience, and you’ve achieved that glint of absolute freedom in Stalin’s eye.”

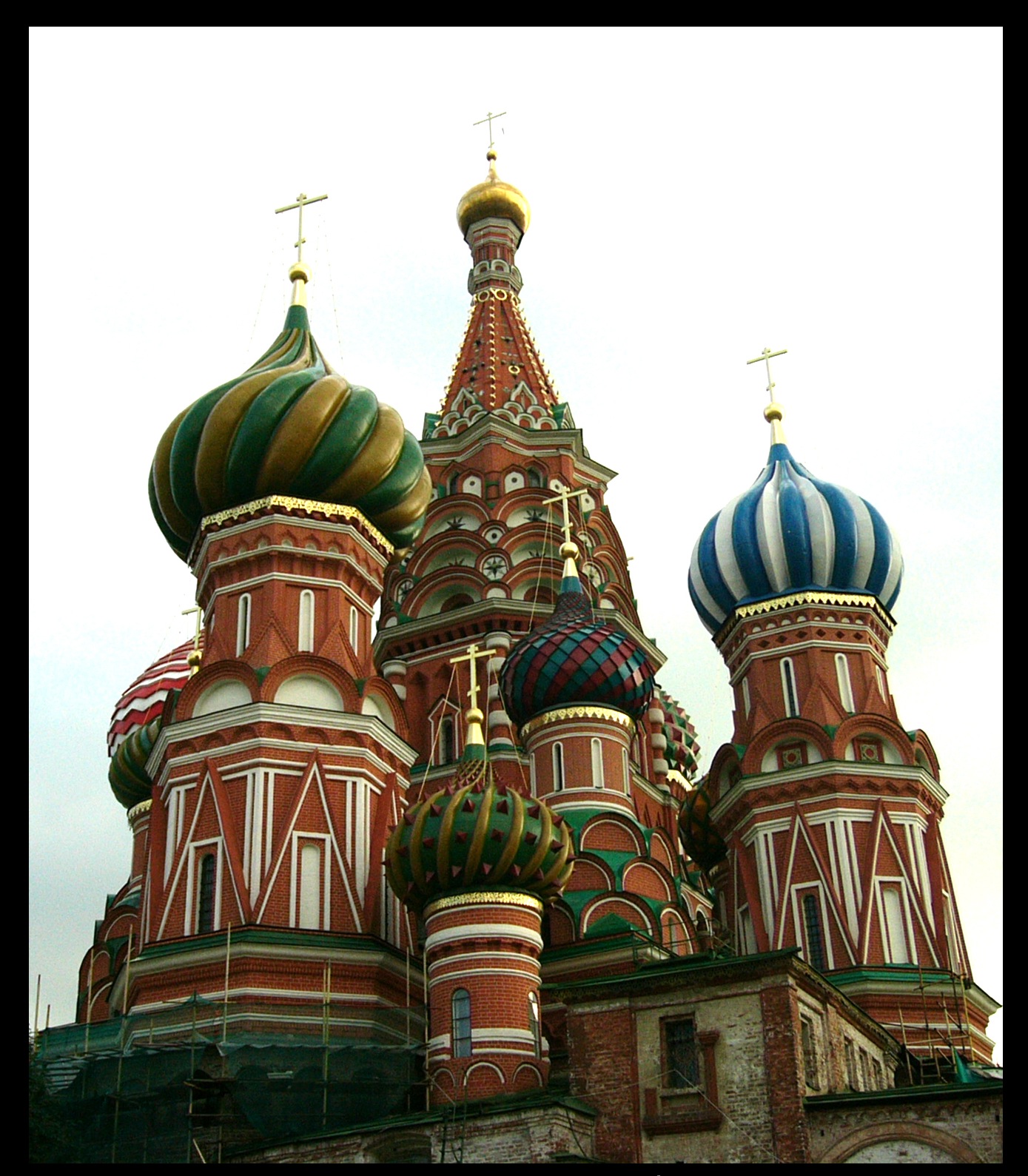

And the people of Soviet Moscow need such a “Power which would / Do evil constantly, and constantly does good” to highlight the hypocrisy of their world. Bulgakov accordingly quotes Goethe’s interpretation of the legend in his epigraph to Master and Margarita, his satirical critique of 1930s Russia. Again, a new wager: Mephistopheles no longer needs to look for souls to seduce; they have signed up in advance. Secularisation has become vociferous atheism, and as the city’s windows trumpet the ‘Hallelujah foxtrot’, Berlioz the polite editor of communist literature, soon to be decapitated by a tram, declares the state’s rejection of religion. The devil sitting beside him is thrilled.

“We say that modern man does not believe in God. But can he at least believe in the devil?” writes Arabov, author of Sokurov’s screenplay. Faust’s narrative has been a medium through which to analyse the condition of society through the centuries. Sokurov’s Faust depicts a weak and clumsy Mephistopheles, squatting and mumbling, breathing heavily and barely able to walk, and a Faust who by contrast resolutely makes his own immoral decisions: in our age it is no longer the devil that tempts man, but man that tempts the devil. Spengler’s theory of the downfall of the west, a “Faustian civilisation”, needs no tempting to restlessly push beyond the boundaries of illicit knowledge, impatient for the infinite. And it must bear the consequences, from the expiry date set on our natural world to the threat of nuclear warfare.

“If you don’t even believe in the devil then you get absolute freedom.” Sokurov’s is the first interpretation to permit Faust the murder of Mephistopheles. But by doing so Faust does not heroically rid the world of evil. Instead, it is his own conscience and any reminders of his guilt that he stones to death. Throw off your limitations, throw away your conscience, and you’ve achieved that glint of absolute freedom in Stalin’s eye.